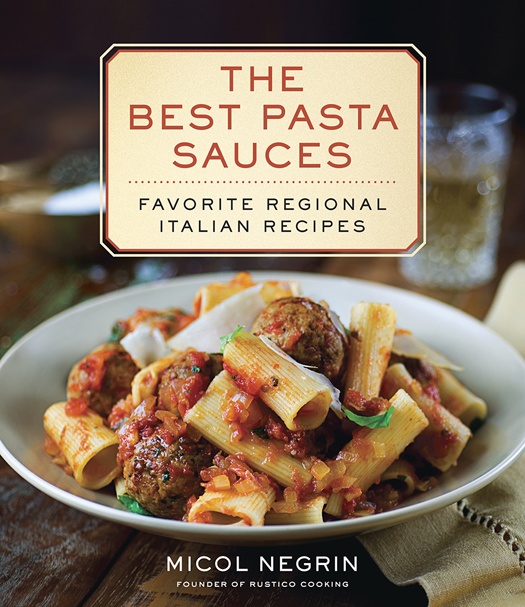

BY MICOL NEGRIN

The Best Pasta Sauces: Favorite Regional Italian Recipes

Rustico: Regional Italian Country Cooking

The Italian Grill: Fresh Ideas to Fire Up Your Outdoor Cooking

As of press time, the URLs displayed in this book link or refer to existing websites on the Internet. Random House, Inc., is not responsible for, and should not be deemed to endorse or recommend, any website other than its own or any content available on the Internet (including without limitation at any website, blog page, information page) that is not created by Random House.

Copyright 2014 by Micol Negrin

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

B ALLANTINE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Photography by Dino De Angelis

Wine pairings by Costas Mouzouras

Negrin, Micol.

The best pasta sauces : favorite regional Italian recipes / Micol Negrin.First edition.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-345-54714-9 (hardback)ISBN 978-0-345-54715-6 (ebook)

1. Sauces. 2. Cooking, Italian. I. Title.

TX819.A1N44 2014

641.814dc23 2014017531

www.ballantinebooks.com

First Edition

Book design by Liz Cosgrove

v3.1

Contents

Introduction

A BRIEF HISTORY OF PASTA

Legend has it that Marco Polo discovered noodles on his voyage to Chinabut nothing could be further from the truth. Pasta had already been a staple in the Mediterranean since the Neolithic era, about eight thousand years ago. The Etruscans (who lived in the tenth century BCE in what is now Tuscany, Umbria, and Latium), as well as the ancient Romans, Greeks, and Arabs, were preparing wheat-based noodles some three thousand years ago. At the necropolis of Cerveteri, an ancient Etruscan city, there are carvings of the tools needed for pasta making (rolling pins, cutters, and boards for rolling the dough) dating to the fourth century BCE. The Roman epicure Apicius described the making of lagane (similar to lasagna, either boiled or baked) and many pasta sauces in his fourth-century book, De Re Coquinaria , and in the twelfth century, the Arab geographer Al-Idrisi wrote about the mills of the town of Trabia, just twenty miles from Palermo in Sicily, where a long, thin pasta known as itryah was made using flour and water for dispatch across the Mediterranean.

Most of the pasta eaten in Italy in ancient times was placed raw in sauce and baked in the oven, without being boiled first. In the Middle Ages, this changed, and new pasta shapes were introduced: some were short, some were filled, and, most important, the art of drying pasta was developed, likely introduced on behest of the Arabs who had settled in Sicily and required staple foods for their long journeys in the desert.

Small shops specializing in pasta opened in Naples and Genoa, as well as in Sicily, and eventually spread across Italy. By the 1300s, Italian pasta-makers had formed guilds. Most significantly, by the 1700s industrial production of pasta began in earnest, making dried pasta available and affordable for more Italians than ever before.

Tomatoes, a New World food, were initially planted as ornamentals rather than as food in Italy. Many botanists thought them poisonous, as they belong to the Solanaceae (or nightshade) family, which includes several toxic plants. It took nearly two centuries before tomatoes became a common ingredient on Italian tables. In the 1700s, tomatoes and pasta became a common pairing, as techniques for growing, processing, and preserving tomatoes progressed alongside the industrial production of pasta. The first tomatoes brought to Italy were likely a yellow variety (hence their name, pomodoro , which translates as golden apple). But before the 1700s, those who could afford to eat pasta often sauced it in ways we would not recognize (or perhaps approve of) today: in ancient Rome, intensely savory ingredients like fermented fish sauce (known as garum or liquamen ) formed the basis of the sauce for fried, boiled, or baked noodles; in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, sweet and salty essences intermingled (honey and black pepper, for instance, or reduced wine and fragrant spices like cumin or rue).

With the advent of industrial pasta production and the spread of pasta to peasant homes, sauces for pasta began to take on many guises. Olive oil or butter, perhaps with grated cheese or toasted bread crumbs, became a common preparation. Boiled vegetables or bits of salted or dried meat and fish were welcome additions. Feast days and banquets called for extravagant pastas featuring slowly simmered meat sauces or rich rags.

Today, if you travel across Italy, you can still find echoes of the medieval and Renaissance sweet sauces, especially at Christmas, when nuts, sugar, and cinnamon frequently lend festive flavor to pastas. Youll also find echoes of the spice trade that fueled much of the Italian economy in centuries past in pasta sauces that call for nutmeg, cinnamon, poppy seeds, caraway seeds, and other spices. But what youll find most of all is a tremendous variety of sauces that draw on the bounty of land and sea, on the ingenuity of the home cook, and on the imperative of letting the pasta itself be the star of the plate. No sauce is so intense as to mask the pasta it is served with. No sauce is so plentiful as to drown the pasta it is tossed with. The sauce is merely a vehicle for enjoying the pasta, and it is a vehicle that changes marvelously from region to region, depending on what local cooks can find in their gardens and on what has informed their cooking over the centuries.

I invite you to join me as we travel across Italys twenty regions for a taste of the countrys most glorious pasta sauces. It is a journey that might surprise you, just as it did me, as you discover unexpected flavor combinations. And it is a journey that will hopefully inspire you, as you experience the seemingly never-ending, always fascinating, and relentlessly delicious world of Italian pasta and sauces.

The Ten Rules of Cooking Pasta

First of all, start with a deep, tall pot. Dont use a saucepan for cooking your pasta, and there is no need for nonstick cookware unless you happen to only have a nonstick stockpot. I suggest a deep stockpot with a colander insert; this will make draining the pasta and reserving some of the pasta cooking water much easier later (no more running to the sink with a boiling pot of water to find a colander; plus, this sort of pot comes in handy when making pasta that is cooked along with vegetables).