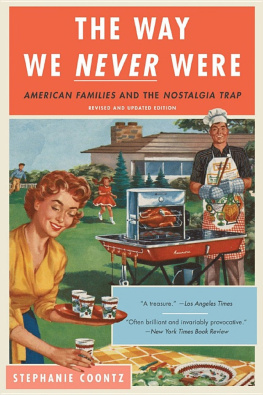

Stephanie Coontz - The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap

Here you can read online Stephanie Coontz - The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Array, year: 2016, publisher: Basic Books, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap

- Author:

- Publisher:Basic Books

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- City:Array

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

We Never

Were

Nostalgia Trap

STEPHANIE COONTZ

I0

HIS book began as a conventional chronological account of American family life from 1900 to 1990, a sequel to my previous book, The Social Origins of Private Life: A History of American Families, 1600-1900. Since publication of that book, I have received numerous speaking requests from nonacademic audiences-hospital ethics committees concerned about how to define families, psychologists' and social workers' associations, church groups, Rotary clubs, and labor organizations. In each case, people were seeking a way to assess the conflicting messages they were receiving (and often feeling) about the changing forms and functions of American families. Gradually, I began to see that one contribution I could make to their debates was to place the urgent concerns I heard at these meetings in some sort of historical perspective.

At first, I unconsciously tried to incorporate this project into my original outline. The result was a mess-detailed historical chronologies interspersed with occasional comments on the applicability of some past event to modern family dilemmas. Susan Armitage, director of American Studies at Washington State University, first suggested that the prospectus for a sequel to my previous work now contained within it quite a different book on various myths about past family life. Simultaneously, a number of op-ed editors at various newspapers challenged me to demonstrate the contemporary relevance of family history in more accessible form. Accordingly, I reorganized the book to highlight particular myths and stereotypes, especially those most directly applicable to current debates about family life and gender roles.

I received help in recasting my topic from many sources. My editor at Basic Books, Steve Fraser, provided incisive comments to keep my writing focused. A dedicated group of colleagues and friends from many disciplines and occupations met regularly to help me decide how to organize my discussion: I would like to thank Priscilla Bowerman, Peta Henderson, Jeanne Hahn, Charles Pailthorp, Larry Mosqueda, Jim Ascher, Suzette McCann, and Kathleen O'Shaunessy for their extraordinary commitment of time and energy. I also received helpful advice and criticism from Nancy Hartsock, Steven Rose, Susan Strasser, Russell Lidman, David Marr, Nancy Holm- strom, York Wong, Alan Nasser, Jill Severn, Leo and Sherry Frumkin, Ted Brackman, Gonzalo Munevar, Brian Price, Greg Weeks, Sarah Williams, and Charlotte Raynor.

My research assistant, Paul Ortiz, worked for starvation wages tracking down books and articles, checking footnotes, collecting data, and giving me the benefit of his critical reading of each chapter. Paul Schipper helped me complete many notes in the copyediting stage, as did several of the library staff at the University of Hawaii in Hilo, where I was on exchange at the time. Michael Simmons and John Finnan extricated me from numerous computer crises. I received generous help from successive secretarial teams: Adelle Smith, Peggy Davenport, Cindy Fry, Lupe Valadez, and Mary Hansen, and especially Pam Udovich, who typed and printed my final revisions. The Evergreen State College kindly provided me with a sponsored research grant as well as allowed me an unpaid leave to complete the book, and its library staff were unstinting in their help.

Finally, I would like to thank my family-nuclear, extended, blended, and fictive-who have never confused being "untraditional" with being uncommitted and who have supported me in many ways during the writing of this book. I am especially grateful to my son, Kristopher, for his patience, good cheer, and common sense.

In addition to the individuals listed in my original preface, I would like to thank the following for their contribution to this introduction: for their skill in tracking down sources, often at short notice, Randy Stilson, Ernestine Kimbo, Sarah Pederson, and Sara Rideout of The Evergreen State College Library; Kevin Roddy, Susan Maesato, Thora Abarca, and Helen Rogers of the University of Hawaii at Hilo Library, and research assistants Jacyn Piper and Charlene Cole; for assistance way above and beyond the call of duty, my secretary Julie Douglass; for their astute comments and suggestions, my current editor Jo Ann Miller, my agent Susan Rabiner, and my husband Will Reissner; and, as always, my son, Kris.

S. C.

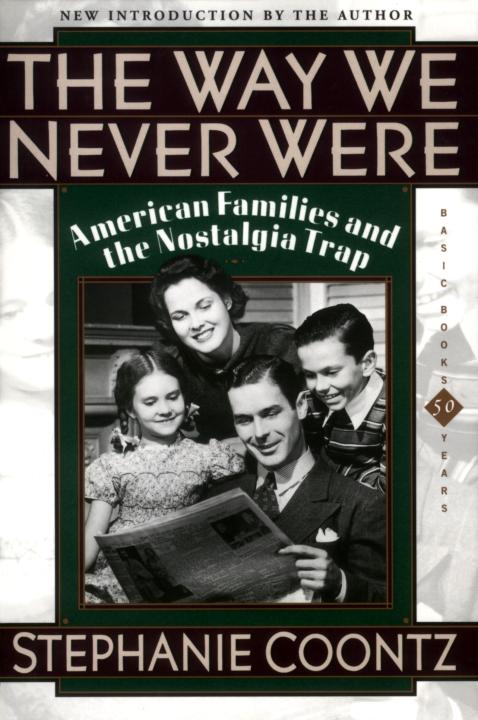

In 1992, during the presidential election campaigns of George Bush and Bill Clinton, then Vice President Dan Quayle made headlines across the country by denouncing a fictional television character, Murphy Brown, for having a child out of wedlock. This book came out that same year, right in the middle of the ensuing debate over changing family values and structures. Although I could not have anticipated Quayle's now famous Murphy Brown speech, I wrote the book because for several years, discussion about America's changing families had been growing increasingly heated. As a family historian, I was concerned that the polemics, on all sides, were based on misconceptions about the past.

My hope was that by exposing many "memories" of traditional family life as myths, I could help point the discussion of family change and family policy in a more constructive direction. I wanted to show that families have always been in flux, and often in crisis. Knowing that there was no golden age of family life, I believed, would enable people to deal more effectively with the problems facing today's families than if they continued to romanticize the "good old days."

In the original introduction, for example, I pointed out that "traditional" two-parent families had never guaranteed women and children protection from economic deprivation or physical abuse. Budget studies and medical records reveal that many families of the past had two standards of living, with male household heads spending money on beer or recreation while women and children went without needed food and medical care. Modem statistics on child support evasion are certainly disturbing, but prior to the 1920s, a divorced father didn't even have a legal child-support obligation to evade. Until that time, children were considered assets of the family head, and his duty to support them ended if he wasn't in the home to receive the wages they could earn. Wife beating was routinely tolerated by police and social service agencies well into the second half of the twentieth century, and spousal rape was legal in most states right through the 1970s.'

Similarly, drug abuse was more widespread at the end of the 1890s than at the end of the 1990s, and the rate of alcohol consumption was almost three times higher in the early nineteenth century than it is currently. Prostitution and serious sexually transmitted diseases were also more prevalent in America one hundred years ago than they are today'

In many ways, the response to my book exceeded my expectations. I received hundreds of speaking invitations from groups who wanted to know more about what had and had not changed in American family life. Employed mothers and stay-at-home mothers, as well as single parents of each sex, wrote to me about the stresses and stigmas they faced. I presented my findings to the House Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families, debated Pat Buchanan on Crossfire, and appeared on the "Oprah" and "Leeza" television talk shows. Most important, I got in touch with many other researchers, policymakers, and concerned citizens whose interests lay not in romanticizing the past but in working with today's families, in all their diversity, to help each of them succeed.'

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap»

Look at similar books to The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The way we never were : American families and the nostalgia trap and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.