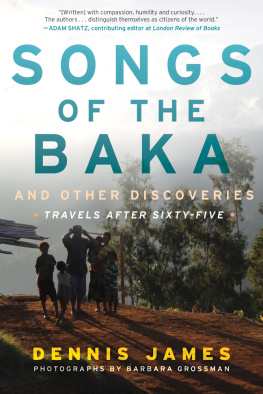

Copyright 2017 by Dennis James

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Algeria: Blood, Sand, and Natural Gas first appeared in the Legal Studies Forum under the title Algeria Journal.

Cuba: State of the Arts first appeared in the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) Report on the Americas.

Cover design by Anthony Morais

Cover photo credit by Barbara Grossman

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-1350-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1352-9

Printed in the United States of America

Dedication

To all the people who welcomed us,

into their countries, into their villages,

and into their homes.

Ones destination is never a place,

but a new way of seeing things. Henry Miller

When you come to a fork in the road,

take it. Yogi Berra

Contents

Introduction

B arbara Grossman and I spent our professional lives practicing law in Detroit, Michigan. We met in 1997, married in 2001, and retired and moved to New York City in 2005.

Among our many common interests is a desire to travel. Raising children during a prior marriage and practicing law as a partner in a small law office left me little time to take more than one-week family excursions into the woods and lakes of northern Michigan and an occasional weekend for professional meetings in cities such as Boston and San Francisco. Barbaras experience was similar, although she had done some traveling in Europe, the Middle East, and South America.

By the time we met, our children had left the nest. We began to travel together, going on several Sierra Club backpacking trips that lasted seven to ten days. Our international trips were initially limited to the tourist magnets of Europe. But after encountering one too many tourist buses, we resolved to seek more isolated, less popular destinations.

In 2002, we went to Vietnam for three weeks, hiring occasional drivers and guides. We had protested against the Vietnam War, and I had counseled and represented draft resisters in my law practice. Not many Americans had explored the country since the war ended. We were curious as to the reactions the Vietnamese would have to us. Rather than displaying hostility, or worse, because of our governments destruction of their country, the Vietnamese, friendly and businesslike, were concerned only with what we wanted to buy. The war? they said. Which war? The Japanese? The French? The Chinese? The Cambodians? Oh, the Americans! Oh, thats all over. Let me show you our new line of silk shirts.

We were hooked. Thus began our odyssey, usually to countries that caused friends and family to worry (needlessly) about our safety and judgment. Over the years, they have learned to accept our choices and simply to ask where we are going next. Their curiosity about our experiences gave rise to the idea for this book.

In recent years, we have incorporated trekking into our travel plans. Hiking from village to village and staying in villages at night has given us the opportunity to see how people in other societies live. This is a felicitous way to learn about other culturesto eat with people, stay in their homes, go into their fields, watch their dances, listen to their music, and hear their stories, myths, and legends. People are proud of their culture and delighted that friendly strangers are interested. The accommodations are certainly not luxuriousmost lack indoor plumbingbut the rewards are immense. Leaving our comfort zone has expanded our view of the world.

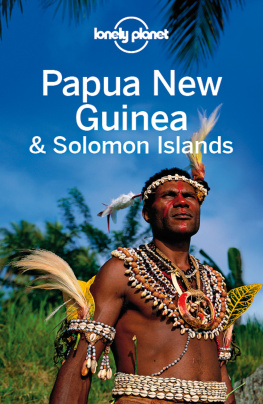

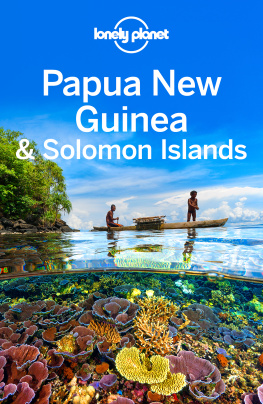

We trekked and stayed with Sherpas in the Langtang Valley of Nepal; tribal village farmers in the Shan hill country of Myanmar; rubber tree farmers in Chinas Yunnan province; the cliff-dwelling Dogon along Malis Bandiagara Escarpment; tribes in the mountains, rivers, and coastal range of Papua New Guinea; and the Baka Pygmy of the Dja Forest Reserve in Cameroon.

We have developed a particular interest in indigenous peoples whose cultures have survived relatively intact for centuriestheir art, music, dance, sexual mores, economic and political hierarchy, and spirituality. How have they resisted change under the pressures of economic globalization and the incursions of western culture? Why do they resist? Are they happy? If so, what do they know that we dont?

Travel is also a way of gaining information about political issues and events of importance. Face-to-face communication with people directly involved in these situations provides valuable insight not available in our mass media.

Other than in unique circumstances, such as in Gaza in 2009 and Cuba in 2013, we avoid tours and choose to travel with only a guide and driver. Because of this, people in both isolated and populous areas often approach us with a smile to ask where we are from and why we have come to their country. In China, they even asked how much money I earned. They frequently invite us into their homes and offer coffee or tea, something that rarely happens when a tour bus pulls up and twenty tourists emerge.

We are not youngI was born in 1938, and Barbara, in 1944. However, we work out a lot and are in good shape, despite our share of late-life malfunctions. I have early Parkinsonism and recently had open-heart surgery, while Barbara has just recovered from knee-replacement surgery. But to the extent that we can travel and trek, we will continue to do so. Our hope is to inspire others who are ambulatory, curious, adventurous, and thoughtful to do the same. This is perhaps the last generation to have the opportunity to observe these cultures before their ways of life or their environments succumb to globalization. And, unfortunately, because of subsequent events, we may already have been among the last tourists to visit some of the amazing places in this worldSyria, Mali, eastern Turkey, Venezuela, and perhaps even Egypt.

In most of the nonwestern cultures we visited, older people, both men and women, are treated with great respect and treasured for their wisdom. Members of the community ensure that their elders are fed and protected from harm. This includes visitors, and our gray hairs made us frequent beneficiaries of this tradition. In Papua New Guinea, we were made honorary elders in a Highland village. In Bali, our young guide asked me how I felt about life, at my age. I thought before I answered and said, Its been a full lifeand getting fuller.

Traveling while older has had its amusing moments as well. While going up the trail in Nepal, we encountered a young man coming down who looked at our gray hair and told us that the only trekking his father did was from the living room couch to the refrigerator. In Palmyra, Syria, a young woman told us that she thought it was wonderful that elderly couples are traveling together. In Venezuela, a checkpoint guard looked at our passports and asked our guide, Where are their children? Why are their children not taking care of them? And so on. But most often, people are amazed that we are strong enough to visit their remote areas and admire us for doing so.