CONTENTS

FEATURE PARKS

OTHER PARKS

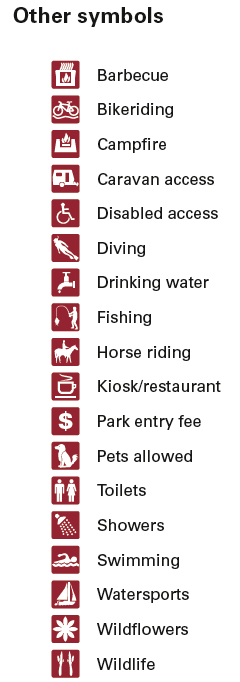

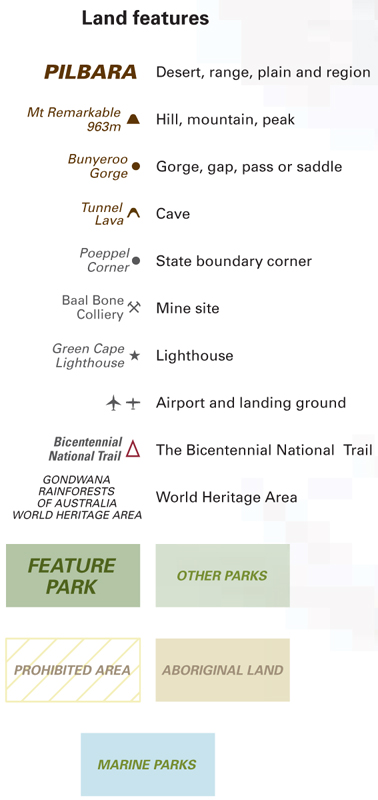

Australia has hundreds of national parks, many of which are significant wilderness areas that protect the continents native flora and fauna, natural landscapes and cultural heritage. The diversity of the park environments is extraordinary: towering forests, arid desert country, alpine meadows, lush rainforest and dramatic coastlines. Within park boundaries are some of the worlds most precious natural features, including Australias most recognisable natural icon, Ulu r u, and the 350-million-year-old Bungle Bungle Range.

In addition to protecting the natural environment, national parks provide places for physical activities, peaceful recreation and recovery from urban stress. Millions of visitors each year can enjoy vastly different experiences, such as walking through rugged gorges in the outback, skiing down snow-laden slopes, snorkelling over vibrantly coloured coral reefs and marvelling at Aboriginal rock art. Apart from a small number of parks including Kakadu, Ulu r uKata Tju t a, and Booderee at Jervis Bay, which are managed by the federal body, Parks Australia, each state and territory defines and administers its own parks. There are, however, common guidelines for visitors to follow.

Other regulations such as those regarding fishing can vary from state to state, and even within a state or territory, so it is wise to check before you visit. In addition to the centrally located state or territory authority, ranger offices are located in many rural centres, and often within parks as well. Some parks, particularly the larger and more popular, have an information centre on site. Contact details are given in the information that appears at the top of the opening page of each park.

National parks need looking after, not just by park rangers but also by everyone who spends time in them (see ). In addition to what park visitors can do to lessen their impact on the environment, volunteer programs help in the maintenance and conservation of parks. Generally you do not need any special skills, just a love of nature and some spare time. In the Northern Territory, national park volunteer work ranges from helping to determine animal populations to cooking for scientists and rangers on remote survey camps. In Victoria, voluntary track rangers are used in the alpine national parks during peak summer periods. Each state and each park has its own particular environmental needs. If you would like to contribute to the protection and management of Australias natural environment, visit your states national park website for more details.

National park guidelines

- Do not disturb or remove flora, fauna or cultural items

- Do not feed animals

- Do not stray from walking or vehicle tracks

- Do not light fires, except as directed in fireplaces provided

- Do not carry or use firearms

- Do not bring pets

- Do not leave rubbish behind

NEW SOUTH WALES

One of the most amazing features of national parks in New South Wales is their diversity. From the arid moonscapes of outback Mungo to the subtropical rainforests of the north-east and the icy peaks of Kosciuszko, these parks protect natural landscapes, provide important sanctuaries for flora and fauna, and guard a rich Indigenous and European cultural heritage. They also provide outstanding recreational opportunities and the chance to experience the environment in its near-natural, and sometimes true-wilderness, state. A leisurely stroll or a strenuous bushwalk, boating, fishing, skiing, wildlife-watching, camping, picnicking and swimming are just a few of the recreational options on offer.

Sydney itself is particularly well endowed, with some of the country's most beautiful national parks, including Sydney Harbour National Park with its rich geological and military history, and pockets of bushland on the edge of the CBD. Royal National Park, on the southern outskirts of the city, was the countrys first national park, declared in 1879.

| New South Wales National Parks and

Wildlife Service (NSWNPWS) 1300 361 967 |

| www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au |

Morning frost lingers upon the low grasses native to this area

PARK INFORMATION

NSWNPWS 1300 361 967 | NPWS Gloucester (02) 6538 5300 | NPWS Scone (02) 6540 2300

SIZE

74 568 ha

LOCATION

300 km north of Sydney; 40 km north-west of Dungog; 65 km east of Scone; 38 km west of Gloucester

ACCESS

From Dungog via Chichester Dam Rd then Salisbury Rd; from Scone or Gloucester via GloucesterScone Rd

BEST SEASON

All year; be prepared for sudden weather changes, snow and subzero temperatures in winter

VISITOR INFORMATION

Dungog (02) 4992 2212 | Gloucester (02) 6558 1408 | www.gloucester.org.au

MUST SEE, MUST DO

TAKE in the stunning view from Careys Peak across the Allyn Valley

WALK in the beautiful snow gum woodlands

SEE the Gloucester River drop 400 metres off the subalpine plateau

SEARCH with a torch at night for gliders gracefully leaping from tree to tree

World Heritagelisted Barrington Tops National Park spans a world of contrasts, from subalpine tablelands and peaks wreathed in swirling mist, to plunging waterfalls and sun-filtered subtropical rainforests in the deep valleys. Dramatic changes in altitude and climate have created an immensely varied terrain, including high plateau areas, steep ridges and deep gorges.

This national park is a favourite with bushwalkers and those keen to enjoy its wild and scenic beauty. Access is mainly along unsealed roads and most visitors use the Dungog approach. At times of extreme weather some roads in the park may be closed or accessible by 4WD only.

Aboriginal culture

The park occupies the traditional domain of several Aboriginal groups the Worimi, Biripi and Wonnarua people for whom the land held spiritual significance and also provided good hunting and bush tucker.

A look at the past

Europeans moved into the area in the 1820s and 1830s for logging and farming and were soon clearing the forest. Within two decades the natural ecological balance had been destroyed, wildlife had dwindled and the Indigenous people were driven off their traditional lands. Although there was talk in the 1920s and 1930s of developing the area and turning the Barrington Tops into a resort, and there was ongoing discussion of logging and road building, conservationists lobbied successfully and Barrington Tops National Park was declared in 1969.