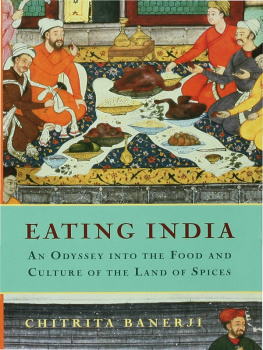

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

Published in India in 2017

by Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

First published in 1991 by Weidenfeld and Nicolson,

as Life and Food in Bengal

Copyright Chitrita Banerji, 1991, 1997, 2007, 2017

Aleph Book Company edition published by arrangement with OR Books/Serif, 137 W. 14th Street, 3rd floor,

New York, NY 10011, US

www.orbooks.com

All rights reserved.

The author has asserted her moral rights.

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by her, which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Aleph Book Company.

ISBN: 978-93-86021-59-5

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For sale in the Indian subcontinent only

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

For my mother, the inspired provider, and in memory of my father, the discerning gourmet,

A Daughters Gift

Contents

Introduction

If you ask a Bengali for the shortest description of Bengali food, the answer is likely to be fish and rice, unless you are speaking to a vegetarian, in which case the answer may be greens and rice. If you are invited to someones house for an elaborate, well-cooked meal that includes varieties of fish, vegetables and meat, not to speak of sweet dishes, your host will probably say, Do please grace my poor hovel with your presence and share our simple meal of dal and rice. In this fertile tropical delta that serves as a basin for innumerable rivers, rivulets and tributaries, it is rice that has been the common sustaining staple from pre-Aryan times until today.

Indeed, the commonest way of enquiring if a person has had a meal, especially lunch, is to ask if he or she has taken rice. Most people, if asked, will agree that a basic Bengali meal will consist of rice, legumes, vegetables and fish.

But the minute you get into the details of cooking, a startling polarisation of ideas and approach begins to emerge. If you happen to talk to someone from West Bengal, a Ghoti, you will probably be told that the uncivilised Bangals from East Bengal know nothing about cooking, that they ruin food by drowning it in oil and spices, that they eat half-cooked fish, that even the best of fish can be ruined by their peculiar habit of adding bitter vegetables to it. For their part, East Bengalis will declare that Ghotis are the greatest philistines on earth, who can cook nothing without making it cloyingly sweet, that the freshest and most succulent of fish will be reduced to leather by the way they fry it, that their miserliness with spices renders all their dishes bland and colourless, indeed that they are hardly even true Bengalis, because they prefer to eat wheat-flour chapatis instead of rice at dinner.

If the warring culinary factions belong to the Hindu and Muslim camps too, then you will also hear about the shortcomings of the Muslim, who cannot cook without onion and garlic and stinks of them himself, and of the Hindu whose meat sauces are no better than cumin-flavoured water. These jocular rivalries between Bengal on this or that side of the borderor this or that side of the River Padma in the days before partitionare likely to leave the newcomer utterly bewildered, for initially the whole range of Bengali food will seem broadly similar wherever you are.

But if you have the mind, the heart, the taste to explore, you will find an enormous variety in a cuisine where richness and subtlety are closely interwoven. With an array of ingredients ranging from water lilies and potato and gourd peel, to fish, meat, crab, tortoise and prawn, the Bengali has also devised a combination of spices that is both ingenious and delicate. From the simplest mashed potato enlivened with mustard oil, green chillies or fried, crushed red chillies, raw onions and salt, to the exquisite prawn coated with spices and baked inside a green coconut, to the hilsa fish in mustard sauce, to the tantalising meat rezala made by MuslimsBengalis take an equal delight in whatever they happen to have. By medieval times we already find in works of literature an extensive list of spices that includes turmeric, chillies, mustard, cloves, bay leaves, cardamoms, cinnamon, cumin, fennel, ginger, fenugreek, asafoetida and nutmeg. The variety of items is matched by a variety of cooking techniques despite the limitation of cooking being done on top of a stove. Vegetables are fried, boiled, roasted on a fire, combined with others and seasoned richly or lightly, or stir-fried with a pinch of whole spices which add their aroma to that of the vegetables. Fish can float in a most delicately suggestive thin stew (the jhol), can be made into a rich and spicy kalia, be fried crisply or be made into a self-contained jhal, red with ground chillies or yellow with ground mustard. Even the humblest of dals gains an unforgettable identity because of the phoron or flavouring added at the end. Every one of these items is eaten separately with a little bit of plain boiled rice. But even that plain rice has variety, depending on the size of the grains, the natural flavour of each species and whether it is parboiled or not.

The importance of such gourmet considerations to the Bengali can be measured by a political history written around 1788 by Sayyid Ghulam Husain Khan Tabatabai. In it he wrote that the Bengalis considered the people of Maharashtra uncivilised, not because the latter were continuously carrying out raids in Bengal and pillaging and torturing their victims, but for the unpardonable sin of not adding phoron to their dal! Similarly, a popular story goes that when the British shifted the capital of India from Calcutta to Delhi, those Bengali families who followed because of their work could easily be identified because smoke began to rise from their cooking fires at four in the morning and did not stop till midnight.

But the real food of Bengal, whether Hindu or Muslim, East or West, is not easy to reproduce on a mass scale, nor does it maintain its nuanced flavours after repeated heating or long hours in storage. Perhaps this explains the absence of a successful restaurant serving typical Bengali food in either West or East Bengal, despite the increasing urban trend of eating out. Most places tend to serve an imitation of northern Indian food, as do restaurants run by Bengali people settled in the US or the UK. Even in Dhaka, where Muslim meat dishes appear on the menu in many restaurants, the eating experience is seldom as satisfying as at somebodys house. I remember a restaurant called Pithaghar that bravely opened in Dhaka purporting to serve real Bengali delights like pithas and khichuri with bhuna duck. It did not survive. The kabab joints with their nan bread and varieties of kababs flourish, but there is hardly any difference between those in Dhaka and similar places in Delhi, Lucknow or Allahahad.