Acknowledgements

H undreds of people helped make Venado's walk and this book possible, but foremost among them is Regina Grabrovac (Seaweed), without whom we would have been lost. And thanks to all our collective family members for supporting us one way or another, particularly Pidge Molyneaux, who bought a lot of gear for her grandchildren, Oona Molyneaux for running our resupply when we really needed it, and Paulette Grab for being generally great.

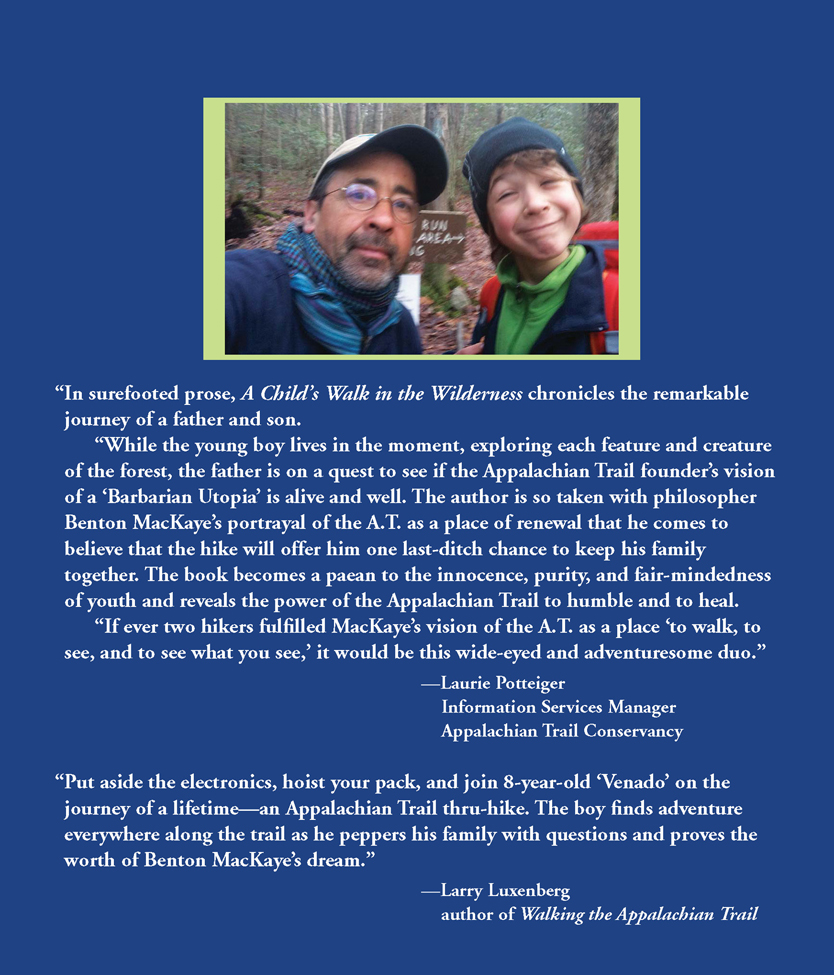

Among the more than 500 fans who lifted our spirits via our Barbarian Utopia Facebook page, Chris Scanlan, Therese Lussier, and Tammy Lee deserve mention for their great participation, as does Laurie Potteiger of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

A list of folks who helped us along the way could really snowball, but I would like to extent a particular thanks to our couchsurfer.org hosts Kimbi and Karl Hagen in Atlanta, and Adam Weber in Pennsylvania, as well as Sonia Lipson in Boston, whose couch we have surfed a long way. Thanks to Marie Celeste Parham, Rachel Bereson Lachow, Breeze, Robin Rieske, Jeff Butt, and Cliff Hall for your contributions to the cause. A shoutout, too, to the Piedmont Appalachian Trail Hikers, and the Appalachian Mountain Club.

Ben Pasamanick and Tony Williams both offered valuable feedback on the manuscript, and Larry Anderson provided me with a copy of his thorough biography of Benton MacKaye. Thanks to you all, and to the many, many who helped us and cheered us on.

THE FLOOD

Water at high level forms a high potential pressure, and the result of its release depends upon the sluiceway. If this be intact the flow becomes controlled and its power made constructive; if weak and leaky the power peters out or spreads disaster. As with water pressure so with soul pressure: its hydraulics are the same. The Puritan would build a dam; but the Barbarian would build a sluiceway.

Benton MacKaye, from the Barbarian Utopia speech given before the New England Trail Conference, January 21, 1927

R ain splatters against the side of the outhouse at Pogo Campsite, where my son and I have found shelter from the easterly winds and steady rain. Inside, with our gear jammed into the corners and our hastily struck tent dripping on the floor, I take boiling water from a small alcohol stove and pour it into a pouch of freeze-dried huevos rancheros.

I think we're going to need a hot breakfast today, I tell my son, Venadoit's his trail name, Spanish for deer. Seven years old, he stands on the toilet seat, poking at a spiderweb with a stick, and knocking debris down into our food.

Whoa, Venado, what are you doing? I ask, looking up at him.

Just playing.

You're not just playing, I say. You're polluting. Now pay attentionthis is our precious food.

As I pack our gear, Venado carefully ties his boots and then puts on the gaiters he wears over them. He slips his belt through the loops that hold up his bright red rain chaps, and dons a heavy rain jacket, hat, neck warmer, and gloves. It's a lot to deal with and I help him with all the lacing and zippers and Velcro. We fit a garbage bag over his small pack, and I lift it so he can find the shoulder straps.

I can do it, he protests.

Yeah, yeah, I laugh. Come on.

Out in the weather the wind-driven rain finds the gaps in our gear. Venado's jacket does not cover the tops of his rain chaps and the rain drips down onto his pants. I'm wearing a twenty-five-cent emergency poncho I bought the year before in Phnom Penh; it's more idea than function, and the heavy linen shirt and cotton T-shirt I wear underneath it go from damp to soaked in the first mile.

Along the way Venado complains about a sore spot on his foot. Working quickly, I unpack our first-aid kit and cut a strip of moleskinthin felt with an adhesive back. I untie Venado's boot, pull down the sock, and press the moleskin down on a growing blister. That it?

Yeah.

Your feet staying dry?

Mmhmm.

I retie the lock knot above the instep on his boot a little looser this time and take a double wrap around the last hooks at the top and finish it off with a double knot. After four days of patching blisters we have the drill down, but it still takes time.

Are you warm? I ask, shivering a little.

Yeah. Are you?

I will be as long as we keep moving.

We march on, punching through patches of knee-deep snow and picking our way along rock-strewn ridgelines. Some people don't think walking in the rain is very fun, says Venado, stopping and looking at the mist blowing between the trees. But look at all that fog down there; it's actually quite pretty. Walking in the rain is lots of fun.

I think we're in a cloud, I tell him.

A cloud?

Fog doesn't happen in the wind, and we're high up, in a cloud.

He takes that in and skips along down the trail, until we hit more snow.

We carry a segment of pages torn from the Appalachian Long Distance Hikers Association's Thru-Hikers Companiona compilation of critical information about the trail. Our pages cover the route from Harpers Ferry to Vermont.

It says there's a hostel five miles from Pogo, but it doesn't open until March fifteenth.

What's today?

The twelfth. Maybe we'll be lucky.

Venado spots a herd of deer leaping through a thicket of thorny vines that he and I call Cambodian rain gear destroyer because, hemming the trail, it has torn my cheap poncho to shreds.

There you go, Venado, you saw your animal.

But we haven't seen an owl, he says, in reference to my trail name, TecoloteMexican Spanish for owl.

No, not yet.

We descend onto the road. After the snow and rock of the trail, the strip of smooth black tar passing through the wet forest affords us some easy walking. We double-check the guidebook. One-third of a mile west.

It's a long third of a mile, as we search for the Free State Hikers Hostel, having no idea what it looks like or even what side of the road it's on. Eventually Venado spots a small white sign on a tree in front of an unremarkable suburban house: Free State. It's not actually free, but it's dry, and the owner, Ken Bone-Pac Berry, a former thru-hiker, lets us in. Venado goes barefoot through the carpeted rooms and plays air hockey with Berry's daughter while I do laundry, throwing everythingeven the tentinto the dryer. We bask in the warmth and comfort, and I don't ask the price until the next morning.

Berry tallies our bill. It's thirty-two dollars for you and for kids we charge by the age. How old are you, Venado?

Seven.

So that's thirty-nine dollars, plus two Pepsis. Forty-one dollars.

It's over our budget, but worth it, and I hand him two damp, dirty twenties and four quarters. Oh, I love this trail money, says Berry, smiling as he smoothes the crumpled bills. He tells us how, after his thru-hike, he wanted to stay connected to the trail, so he and his wife bought this house and turned it into a hostel.

Outside, the rain pours down, one of those long, drenching rains that rolls in warm from the sea and washes all the snow off the mountains. Though tempted to stay another night at the hostel, we decide to hike on, quoting the thru-hiker's motto: No rain, no pain, no Maine.

But we procrastinate over details and decide to weigh our packs. Standing on the scale I heft them one at a time and do the math, subtracting my unburdened weight from that with the pack. Venado's comes in at 14 pounds, a couple of pounds over the ideal 20 percent of body weight for a 60-pound boy. Mine too comes in over the 20 percent target28 pounds for a 135-pound man.

As soon as we eat a couple of meals we'll be light enough, I tell Venado.

Next page