For our daughter, Griffin.

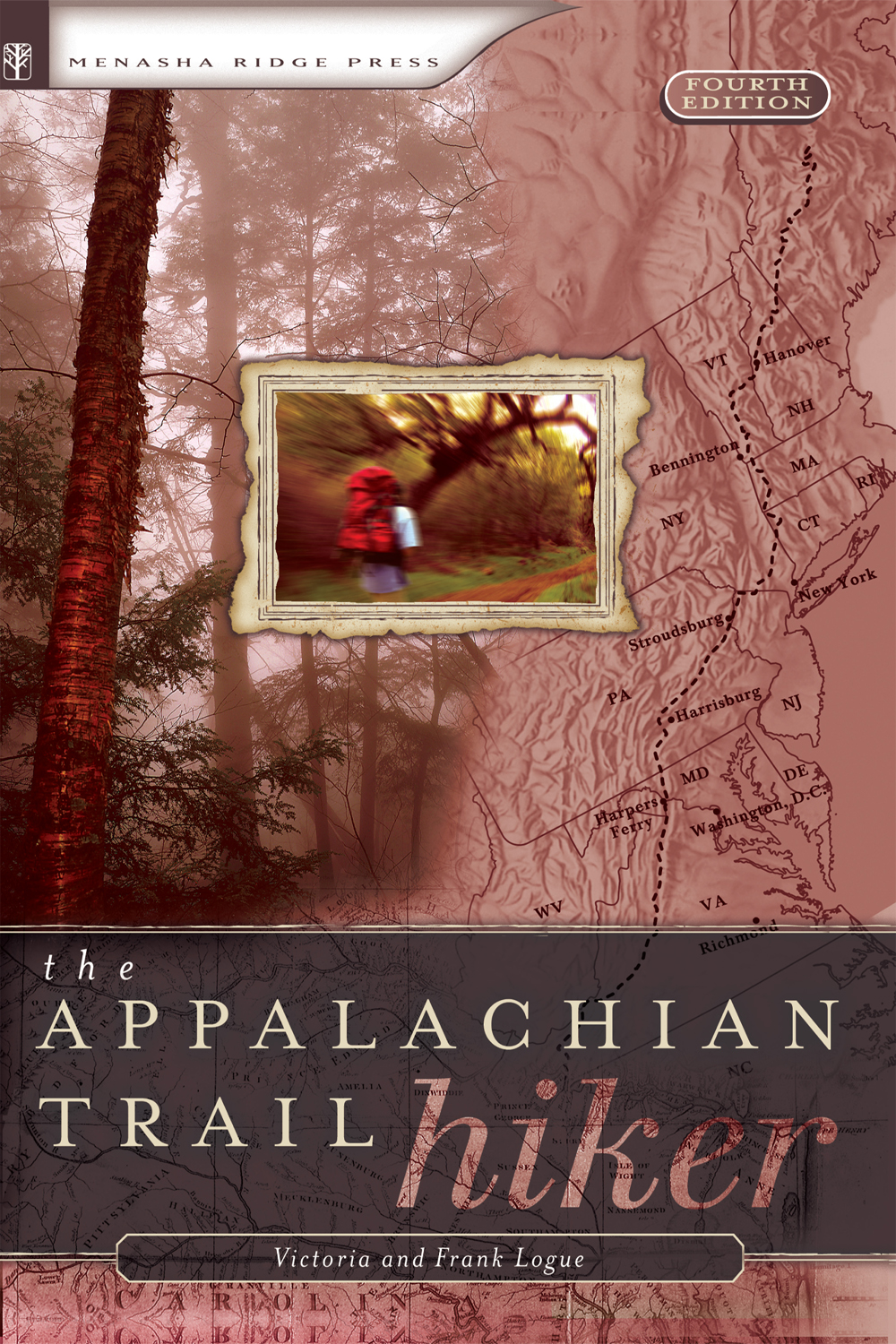

Copyright @ 2004 by Victoria and Frank Logue

All rights reserved

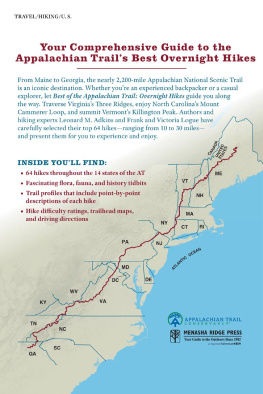

Published by Menasha Ridge Press

Distributed by The Publishers Group West

Manufactured in The United States of America

Fourth edition, second printing 2010

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Logue, Victoria, 1961

Appalachian Trail Hiker: formerly The Appalachian Trail Backpacker: trail-proven advice for A.T. hikes of any length/ Victoria and Frank Logue.

p. cm.

Rev. ed. of: The Appalachian Trail backpacker. 3rd ed. c2001.

ISBN 978-0-89732-583-7

1. HikingAppalachian TrailGuidebooks. 2. BackpackingAppalachian TrailGuidebooks. 3. Appalachian TrailGuidebooks. I. Logue, Frank, 1963 II. Logue, Victoria, 1961 Appalachian Trail backpacker. III. Title.

GV199.42.A68L64 2004

796.510974dc22

2004059281

Cover design by Palace Press International, Inc.

Text design by Palace Press International, Inc. and Annie Long

Photos by Victoria and Frank Logue, Travis Bryant, and Russell Helms

Illustrations by Travis Bryant

Menasha Ridge Press

P.O. Box 43673

Birmingham, AL 35243

www.menasharidge.com

Appalachian Trail Conservancy

P.O. Box 807

Harpers Ferry, WV 25425

www.appalachiantrail.org

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

W E REMAIN THANKFUL TO THE MANY HIKERS WHO HAVE USED THEIR THOUSANDS OF MILES OF EXPERIENCE ON THE A.T. TO HELP SHAPE THIS BOOK THROUGH THE THREE PREVIOUS EDITIONS.

For this fourth edition, we would like to particularly thank Laurie Potteiger of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy for her ongoing assistance, both with this book and in the many others ways in which she educates and encourages A.T. hikers. We would also like to thank the following hikers who have completed the A.T. at least once in recent years who generously offered their feedback to this revised edition: Chris Bagby, Alan Beck, Steve Bekkala, Dennis and Mary Ann Giancola, and Lamar and Robert Powell. We are thankful for their assistance in keeping this book up to date so that it can be as helpful as possible to new generations of A.T. hikers. Any errors which remain are our own.

C hapter O ne

Following the Blazes

Following the blazes. There is a sense of mystique to that simple phrase that brings to mind the expedition of Lewis and Clark or the travels of William Bartram. Imagine wandering off into the woods to face the unknown, perhaps discovering things as yet undiscovered. At the very least, the Appalachian Trail (A.T.) offers you an introduction to nature in both her splendor and glory as well as her very worst.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL

T he Trail, which winds through the Appalachian Mountains of 14 Eastern states, was the vision of Benton MacKaye (Kaye rhymes with sky) and others who had kicked around the idea for more than ten years. In 1921, MacKaye took the initiative and proposed the project in an article in The Journal of the American Institute of Architects.

MacKayes original intent was to construct a pathway that would create an opportunity for American families to commune with nature. His trail would extend from the highest peak in the North to the highest peak in the South, from Mount Washington (New Hampshire) to Mount Mitchell (North Carolina). His plan had four parts: 1) to create the trail itself, 2) to build a series of shelters, 3) to create community camps, and 4) to build food and farm camps located along the trails length. Although MacKayes larger economic plan for the Appalachian Trail never gained support, it is nevertheless the reason for the Trails existence today. With a continuous trail in easy reach of major cities, MacKaye argued,

There would be a chance to catch a breath, to study the dynamic forces of nature and the possibilities of shifting to them the burdens now carried on the backs of men& Industry would come to be seen in its true perspectiveas a means in life and not as an end in itself.

Less than a year after MacKayes article appeared in the architectural journal, the New YorkNew Jersey Trail Conference began work on a new trail with the goal of making if part of the A.T. In the Hudson River Valley, the newly built Bear Mountain Bridge would connect the future New England trail with Harriman State Park and, eventually, Delaware Water Gap in Pennsylvania.

Seeing that trail work had begun, in 1925 MacKaye and others formed the Appalachian Trail Conference to help guide the volunteers completing the Trail. During the next ten years, over 1,900 miles of partially connected trail were completed. In 1936 Myron H. Avery (who would lead the Appalachian Trail Conference for 20 years as president) finished measuring the flagged route of the Appalachian Trail and became the first 2,000-miler a year before the completion of the Trail.

White Blaze of the Appalachian Trail

On August 14, 1937, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers cleared the final link in the 2,025-mile-long A.T. On a high ridge connecting Spaulding and Sugarloaf mountains in Maine, a six-man CCC crew cut the last two miles of trail. The route of the Trail was not as originally envisioned by MacKaye; it was longerstretching from Mount Oglethorpe (the southern terminus of the Appalachians) in Georgia to Katahdin in Maines Baxter State Park.

The A.T. met with misfortune the following year; a hurricane demolished miles of trail in the Northeast. Meanwhile, the decision to extend Skyline Drive in Virginia (under construction at the time) with yet another scenic routethe Blue Ridge Parkwaydisplaced 120 more miles of the recently completed route. It wouldnt be until the world settled down to rest from World War II that the trail would once again be made continuous.

In April of 1948, Earl Shaffer packed his Mountain Troop rucksack and headed for Georgia. The Long Cruise, as Shaffer referred to his trip, started on Mount Oglethorpe and ended some 2,050 miles and four months later on top of Katahdin. Shaffer, who had fought in the Pacific during World War II, undertook the continuous thru-hike to walk the war out of my system, as he would later write. His hike earned him the distinction of being the A.T.s first thru-hiker.

In 1948, many considered Shaffers thru-hike a stunt, but the dream of long-distance hiking spawned other long-distance trails, including the Pacific Crest Trail, which runs from Mexico to Canada, and the Continental Divide Trail, which follows the Continental Divide from Mexico to Canada.

Since 1948, when Shaffers lone expedition carried him across construction- and hurricane-torn trail, the A.T. has seen many changes. Each year the Trail undergoes relocations and other improvements to its route, causing the trails distance to change almost annually. From the original 2,025 miles it has stretched to more than 2,100 miles.

Legislation passed in 1968 and 1978 gave the National Park Service the power (and the money) to purchase and protect a corridor of land from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Katahdins Baxter Peak. Less than one half of one percent of the trail remains unprotected.

Millions of people visit the Appalachian Trail annually. Whether spending a day hiking along its trails or half a year attempting to thru-hike its length, they are still inspired by MacKayes dream of following the blazes.

A BRIEF TOUR OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL

T he Appalachian Trails southern terminus is on Springer Mountain in Georgia. With a total of 75.4 miles, Georgias trail elevation ranges from 2,510 feet to 4,461 feet (Blood Mount Shelter). Georgias brief section of trail is characterized by short, steep ups and downs. Although rising at times to elevations of over 4,000 feet, the Trail is mostly along undulating ridges at elevations of about 3,000 feet. The weather is comparable to lower elevations in northern Virginia and Maryland. Those tempted by the southerly latitude to plan spring break hikes in March may encounter sleet or snow. In federally designated wilderness areas (about half of the Trail in this state) authorities request hikers to camp out of sight of the Trail. The A.T. is crowded with thru-hikers in March and the first half of April.

Next page