Appalachian Odyssey

Walking the Trail from Georgia to Maine

Steve Sherman & Julia Older

Preface

Most couples start out with a mortgage on a new house or maybe a brand-new bouncing six-pounder to add to the general census. It didnt work out that way for us. Our sweet nothings were transformed overnight into wild romantic chatter about lightweight sleeping bags, lightweight foods, and lightweight lives. Why dont we hike the whole Appalachian Trail? Why not?

We met over a novel and a collection of poetry we were working on at the MacDowell Colony, a writers and artists retreat in the backwoods of Peterborough, New Hampshire. One of us had arrived from So Paulo, Brazil, a concrete Bird of Paradise with more than six million inhabitants, a congested, burgeoning, poverty-stricken, pollution-mindless international cog in the grinding gears of industry and progress. The other had flown in from Fairbanks, Alaska, where oil greed has turned old-timers and outsiders alike into money-mad maniacs of the dollar bill.

In transit from these outposts, we had both stopped awhile in New York and Boston to renew our kinship with hardcore urban life. Fortunately, two Americans of foresight, Marian MacDowell and Benton MacKaye, saved us from more seamy examples of civilized terrorism. Mrs. MacDowell, wife of the American composer Edward MacDowell, had established the Colony, quiet, secluded, wooded, and lofty. The Colony and nearby snow-capped Mt. Monadnock, as pristine as when Thoreau climbed it, joined to focus our dream. We wanted to get away from it all, to go back to the roots of our origin, to hike Benton MacKayes Appalachian Trail.

Now usually men propose a primrose path. Steve proposed walking a 2,000-mile footpath from Georgia to Maine through the wilderness of the Appalachians, the longest continuously marked trail in the world. Julia accepted. Besides, we wouldnt have to pay rent.

Steve, having bicycled across the continent and written about his experiences, knew that for ideas to pass from true confessions to true stories, commitment is merely the beginning. So with the Boy ScoutGirl Scout motto burned into our hearts, we prepared to Be Prepared.

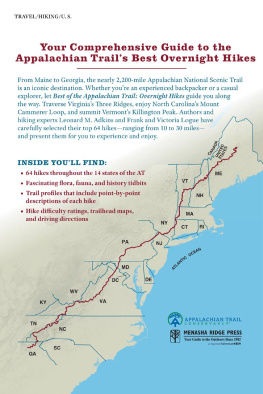

First on our list was to read every book and pamphlet on the Appalachian Trail. Benton MacKaye, a visionary, first conceived of a continuous trail as the backbone of a natural primitive environment. The article in which he expounded his idea in 1921 sparked interest among existing northeast hiking and outdoor clubs. The following year the first section of the Trail was opened and marked in the Palisades Interstate Park, New York. The Trail, originally estimated at 1,200 miles, was completed in 1937. Major growth of urban areas near the Trail has since caused it to be re-routed through more scenic and isolated regions, resulting in an additional 800 miles.

Today, hikers may follow diamond-shaped galvanized metal markers  as well as painted white trail blazes from Springer Mountain, Georgia, all the way to Mt. Katahdin, Maine. Along the summits and down the valleys, a chain of more than 230 lean-tos provide hikers with shelter from the elements. A 35-mile stretch of exposed mountaintops in the Presidentials of the White Mountain Range, however, forces hikers to lodge in Appalachian Mountain Club huts.

as well as painted white trail blazes from Springer Mountain, Georgia, all the way to Mt. Katahdin, Maine. Along the summits and down the valleys, a chain of more than 230 lean-tos provide hikers with shelter from the elements. A 35-mile stretch of exposed mountaintops in the Presidentials of the White Mountain Range, however, forces hikers to lodge in Appalachian Mountain Club huts.

In 1968, the Appalachian Trail was designated a National Scenic Trail by Act of Congress. Through the National Trails System Act, the Appalachian Trail comes under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Interior, with the United States Forest Service assuming responsibility for those parts of the Trail that pass over Forest Service land. Individual hiking clubs continue to maintain sections of the Trail within their states.

These clubs join with their organization and representation to form the Appalachian Trail Conference, which meets every other year. Club members, public officials, life members, and individual members meet to discuss Trail-related problems with the Board of Managers, composed of Conference officers and three persons each from the six districts into which the Trail is divided.

These districts are: 1. Southern District (Georgia and North Carolina in the Great Smoky Mountains); 2. Unaka District (North Carolina from Big Pigeon River, Tennessee and Southern Virginia); 3. Maryland and Virginia District (Northern Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland); 4. Pennsylvania District (all sections of Pennsylvania); 5. New York and New Jersey District (all sections of these states); 6. New England District (all sections of Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine).

We were to walk through fourteen states. We had three months till countdown in mid-April, when the mountain crests would be warm enough to receive us. Three months to foot our bill, to tone our flabby muscles, to get rid of our sedentary writers cramps.

One author we read told us he lost twenty pounds hiking the Trail in the first two weeks. We started swallowing cookies by the cookie sheetful, eating spaghetti by the pasta pound, drinking milk by the carton gallon, all to stave off visions of blowing from the mountains like dandelion fluff. For training we climbed ice-encrusted Mt. Monadnock when no other fool ventured out of house to turn over the motor of his car. The day we shelled out $100 for lug sole hiking boots was the first big economic point of no return. We looked each other straight in the eye and clomped out the door for our daily five-mile forced march. Those three months of preparation were a time of wonder and doubt.

Why were we hiking the Appalachian Trail? Because we wanted to touch the land directly, to re-confirm our trust in the slow but unconquerable ascendancy of nature over man, to test, to accomplish, to learn. Were the rumors right that most of the waters of our country were contaminated? Was there no place to hear the living rhythms of the woods? And what about America the Beautifulanother jaded catchphrase to divert the truth that our cities were ugly?

Benton MacKaye wrote, The old pioneer opened through a forest a path for the spread of civilization. His work was nobly done and life of the town and city is in consequence well upon the map throughout our country. Now comes the great task of holding this life in checkfor it is just as bad to have too much urbanization as too little. America needs her forests and her wild spaces quite as much as her cities and her settled places.

Three months is not a long time to sprout an idea such as ours and cook it in your wok. We were fortunate, however. We may not have been altogether footloose in our four-pound clod-hopping boots, but we were fancy free and, above all, optimistic that what we would discover between the blisters and blizzards would be worth 4 months of our lives, worth spending our wad. We had gone the nine-to-five route like everyone else, but we had each reached the same conclusion individually: Time is only of consequence when you are pursuing your own disciplines and beliefs.

We walked from south to north, the idea being to follow spring as it blossomed northward, and to miss the blackfly season at the beginning of summer in Maine. The latter reason was the better one. Hikers we met venturing from north to south looked as if they had stumbled from a science fiction scenario. As for our revery of spring, we were not prepared for the wintry landscape and the snow flurries that awaited us on April 11 in the South. Our super-light, ultra-modern sleeping bags worked mostly on theory, one miscalculation that we would correct next trip.

At times we remembered Benton MacKayes warning about too much urbanization. Interstate highways loomed too close to the Trail in the middle states. At times the body was more willing than the spirit to trudge ahead.

as well as painted white trail blazes from Springer Mountain, Georgia, all the way to Mt. Katahdin, Maine. Along the summits and down the valleys, a chain of more than 230 lean-tos provide hikers with shelter from the elements. A 35-mile stretch of exposed mountaintops in the Presidentials of the White Mountain Range, however, forces hikers to lodge in Appalachian Mountain Club huts.

as well as painted white trail blazes from Springer Mountain, Georgia, all the way to Mt. Katahdin, Maine. Along the summits and down the valleys, a chain of more than 230 lean-tos provide hikers with shelter from the elements. A 35-mile stretch of exposed mountaintops in the Presidentials of the White Mountain Range, however, forces hikers to lodge in Appalachian Mountain Club huts.