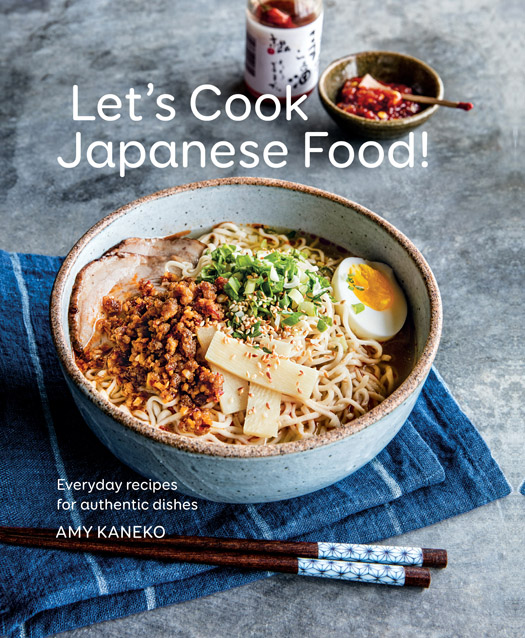

Lets Cook

Japanese Food!

AMY KANEKO

Photography Aubrie Pick

Lets Cook Japanese Food!

Whats a nice girl from New Jersey doing writing a Japanese cookbook? Quite simply, I wanted to share my experience of the delicious and easy everyday meals that I encountered in Japan with my friends and family here in North America.

I decided to live in Japan in my 20s on a whimit appealed to my sense of adventure. So I took a couple of language classes and took off for Tokyo. I knew little of Japanese cuisine other than sushi. As a low-paid conversational English teacher, my meal budget didnt include high-end sushi, so I started to explore the full range of Japanese dishes. Tokyo has a tremendous selection of all kinds of food. I tried it all.

That first year, I subsisted on a lot of takeout and found a few local restaurants where the owners got to know me and delighted in sharing new foods with me to see how Id react. There were few things that I found too strange to trytentacles, grilled eel, fermented soybeans, fish eggs, unfamiliar root vegetablesyou name it, I ate it. And loved it. Among the things I ate most often were the Japanese versions of Western-style foods, like hamburger, curry, fried cutlets, eggs, and morethings that I didnt know were really common in modern Japanese diets and just as Japanese as sushi.

Upon returning to New York, I missed these dishes and began watching the Japanese cable TV channel to get recipes. I moved to San Francisco for a job, and there I connected with a friend of one of my English conversation students, Shohei, who became my husband. He was transferred to Tokyo for work, and I went along. My Japanese coworkers and new in-laws were terrifically helpful in encouraging my Japanese food habit, patiently showing me ingredients, teaching me recipes, and introducing me to new dishes.

When Shohei and I moved back to San Francisco, I wanted to keep cooking Japanese food for him, and then later, when we had kids, for all of us. We now eat Japanese food at home at least three days a week and usually the type of dishes found in this book. I am happy to share these recipes and stories in the hope that you, too, will become a fan of Japanese cooking and will integrate it into your meals and parties. With this book, you will soon be cooking Japanese food with ease! I hope you love it. Itadakimasu (lets eat)!

AMY KANEKO

Getting Started

There are a few basics that you might want to keep on hand so you can cook from this book anytime. Stock your kitchen with the items in the Shopping List below and you will be ready to make most of the recipes in this book. Ive also provided a detailed list of everything youll need in the . A primer on deep-frying, along with the recipe notes throughout the book, will help you learn essential cooking techniques.

(Good luck and try hard to cook Japanese food!)

(Good luck and try hard to cook Japanese food!)

LEARNING HOW TO DEEP-FRY, JAPANESE STYLE

Many cooks are afraid of deep-frying, viewing it as difficult and messy, and many eaters imagine that the food will be greasy. If you follow a few easy rules, frying can be simple and neatcorrectly prepared Japanese deep-fried foods are never oily, but light and crispy.

Set up a workstation with the flour, egg, and panko for breading the food lined up in their order of use. A wok or a deep, wide saucepan works well. Have a pair of long cooking chopsticks or tongs, a slotted spoon, or a spatula handy for transferring ingredients in and out of the pan safely and with a minimum of splashing. A deep-frying thermometer keeps track of the temperature of the oil, but if you dont have one, here is a simple test that you can use whenever you are deep-frying: When you think the oil is hot, hold a wooden chopstick upright in it. If small bubbles form immediately around the chopstick, the oil is ready. Use a wire rack for draining (paper towels are an easy alternative), and a small skimmer is handy for scooping stray fried bits out of the oil so they dont burn.

Always deep-fry food in small batches. If you crowd the pan, the oil temperature will drop, causing the foods to absorb the oil. After you remove a batch from the pan, check that the oil has returned to the correct temperature before you fry the next batch or the food will be greasy.

SHOPPING LIST: MUST HAVES

Chili bean paste

Dashi

Mirin

Miso

Panko

Rice

Rice vinegar

Sake

Sesame oil

Soy sauce

Sugar

Tonkatsu sauce

Worcestershire sauce

FREQUENTLY USED INGREDIENTS

Cornstarch

English or Japanese Cucumber

Eggs

Eggplants

Ginger

Garlic

Green onions

Ground beef, chicken, and pork

Kabocha pumpkin

Onions (yellow)

Tomato ketchup

Tofu

Equipment

Equipment needs for cooking these recipes are undemanding. A few specialized tools, such as a rice cooker (which I highly recommend) and a mandoline, make some of the common tasks of Japanese cooking a little easier, but most tasks can be accomplished with the same everyday equipment you use for cooking Western meals.

Chopsticks: Found in Japanese restaurants everywhere, chopsticks ( ohashi ) seem to make your Japanese food taste better and more authentic. They come in many materialsbamboo and other wood, plastic, metaland styles and in a range of prices, with prized hinoki -wood chopsticks at the top of the pile. Chopsticks in any style will accomplish their main task of ferrying your delicious cooking from bowl to mouth. Waribashi (disposable wooden chopsticks) are inexpensive and can be bought by the pack.

Long cooking chopsticks, once you get the hang of working with them, are the best tools for turning hot foods, especially when frying.

At a place setting, ohashi should be laid horizontally on the table below the main plate, with tips facing left for a right-handed person and right for a left-handed person. The tips are often placed on a chopstick resta small, decorated stand made of ceramic or other material. Keep in mind the following rules of etiquette, too: never leave your chopsticks stuck straight up in a bowl of rice, and dont use them to pass food to others, chopsticks to chopsticks, because both recall funeral customs. Also, never point with your chopsticks or spear your food with them. Its just not nice.

Drop-Lid: Known as an otoshi-buta , this wooden lid, which has a small wooden handle on top, fits just inside of a pot rim. It floats directly on top of the simmering foods, keeping them from moving around, helping to spread the flavors of the liquid evenly, and preventing the liquid from cooking away. Nimono (simmered) dishes such as employ this specialized lid. I make my own by shaping a disk of aluminum foil, which works passably well, except that you have to remember to use a potholder when fishing it out at the end of cooking, as it gets very hot. An Asian kitchen supplies store or website will have drop-lids in different sizes to fit your pots or you can improvise, as I do.

(Good luck and try hard to cook Japanese food!)

(Good luck and try hard to cook Japanese food!)