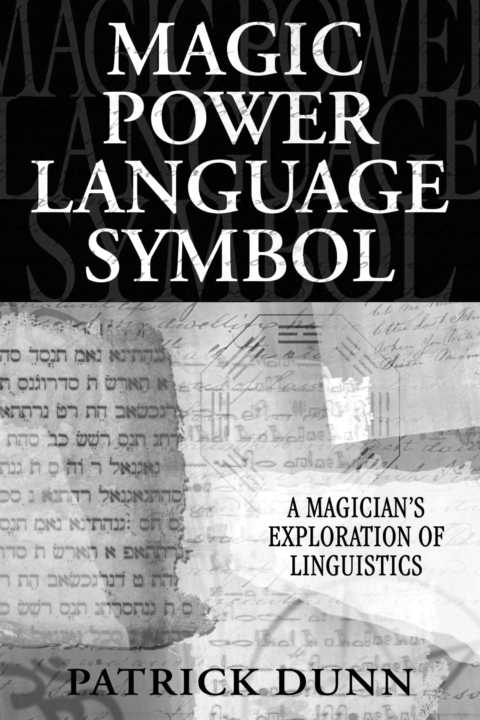

Patrick Dunn has studied witchcraft, the Qabalah, chaos magic, and anything else he can get his hands on. In addition to obtaining his PhD in literature, he has studied linguistics and stylistics. He lives in Illinois, where he teaches English literature. Dunn is also the author of Postmodern Magic: The Art of Magic in the Information Age.

To Write to the Author

If you wish to contact the author or would like more information about this book, please write to the author in care of Llewellyn Worldwide and we will forward your request. Both the author and publisher appreciate hearing from you and learning of your enjoyment of this book and how it has helped you. Llewellyn Worldwide cannot guarantee that every letter written to the author can be answered, but all will be forwarded. Please write to:

Please enclose a self-addressed stamped envelope for reply, or $1.00 to cover costs. If outside the U.S.A., enclose an international postal reply coupon.

Many of Llewellyn's authors have websites with additional information and resources. For more information, please visit our website at http://www.llewellyn.com.

For Eric

People write books for many reasons: desire for fame, desire for money, desire to fill a gap in knowledge, desire to see their name in print, temporary insanity, divine command ...

But people help other people write books for one reason: they care.

Thank you:

Mom: for everything, from morel hunting to tarot cards to last week's phone call.

Chris: for reading the manuscript and offering your suggestions. I can say with certainty that they improved the book tremendously.

Eric: for evenings of coffee, books, and philosophical arguments. Your comments about the semiotic web and reductive materialism gave me the impetus to write this book. And you turned me on to Buber, as well.

Ed: for years of good debates about magic, religion, and rationality, good suggestions about music and reading material, as well as the computer program that saved me hours of work on this particular book.

Peter: for your friendship and suggestions. Thanks especially for listening politely when I go on about irregular Hebrew verbs and the like.

Betty: for margaritas and conversations, not to mention suggesting half of the linguistics articles and books that appear in this one's works cited.

Richard: for making my life beautiful, giving me faith in myself, and loving me as I love you-with a love that holds the stars in place.

Also thank you to various spirits whom I will not name here, as well as gods, daemons, angels, ascended masters, and what all else I have no idea exists, but may: in other words, however the undifferentiated substance of infinite qualities manifests to my little dual mind: thanks.

I'm also one of those people who writes with a soundtrack. Therefore, thanks to the following musicians, who didn't know that they helped me write this book, but did:

The Adicts

Apocalypse Hoboken

Atmosphere

Cake

Cramps

Dropkick Murphys

Eddie and the Hot Rods

The Faint

Guttermouth

Jets to Brazil

me chris

Motion City Soundtrack

Mouthwash

Nirvana

Operation Ivy

Pitchshifter

The Pogues

The Ramones

Rancid

Randy

Soul Coughing

The Streets

The Strokes

XI

f you're looking for magical words, you really can't do better than abracadabra! No one really knows what abracadabra means, if it ever meant anything. Its earliest mention is in a recipe for an amulet. Why this word-out of countless words engraved on charms, talismans, and tablets from the ancient world-survived is a mystery as well. Why do stage magicians not shout, for example, "Abrasax!" or "Abalatha!" Why abracadabra?

f you're looking for magical words, you really can't do better than abracadabra! No one really knows what abracadabra means, if it ever meant anything. Its earliest mention is in a recipe for an amulet. Why this word-out of countless words engraved on charms, talismans, and tablets from the ancient world-survived is a mystery as well. Why do stage magicians not shout, for example, "Abrasax!" or "Abalatha!" Why abracadabra?

I fantasize that perhaps the word itself ensured its survival and popularity. Perhaps it serves as a reminder that real magic, no matter what stage magicians do with their trickery, still exists. Abracadabra could provide the key to magic.

One possible origin for the word is an Aramaic phrase: avra kedabra. This sentence means "I create as I speak." Aramaic is a language closely related to Hebrew; Jesus, when he spoke to friends and relatives and God, spoke Aramaic. The verb avra, "I create," in Aramaic is cognate with the verb evra in Hebrew. But Hebrew makes a distinction between different types of creation: if you make something from nothing, you say "evra," but if you make something from something else, you say "etzor." So abracadabra is saying, "I create something from nothing when I speak, just as my words come from nothing." Yet in the relevant cosmologies, only God can create out of nothing. Evra is a verb for God to use, not humans. Therefore, to say abracadabra is to speak an incantation of apotheosis.

I don't care much about apotheosis. But I do care about language and magic. There are six thousand languages on Earth, give or take, and every healthy child will learn at least one of them. Children learn language effortlessly, without study or memorization, and while they sometimes make amusing mistakes, they make far fewer than any adult learning a new language would. The speed with which children learn language is evidence that there's something about it that's ingrained in our makeup as humans.

Magic is not as universal as language, but it comes close. Most cultures have some concept of magic, and the majority of people on Earth believe in it to a greater or lesser degree. Some materialists might deplore that state of affairs as evidence of regrettable ignorance. But clearly, just as there is something inborn in humans that compels us to learn language, there's also something inherent in humans that encourages us to learn magic.

My goal in this book is to explore the ways in which magic and language interact with each other. Attitudes toward language not only shape magic in the past and present, but the sciences of linguistics and semiotics illuminate the study of magic in interesting ways. After my first book, many people wrote to me expressing a desire for a more scholarly treatment. Yet I did not want to write a book of mere scholarship; I wanted to write something practical as well as edifying. My first book contained many exercises and rituals; this book contains few. My first book contained techniques; this one contains theories. Yet the magician seeking practical techniques or even spells won't come away empty-handed. On the contrary, this book contains information on the structure of incantations, glossolalia, evocation and invocation, mantras, and meditation. For those who want techniques, this book explores them in greater depth than would a book of mere step-by-step instructions.

f you're looking for magical words, you really can't do better than abracadabra! No one really knows what abracadabra means, if it ever meant anything. Its earliest mention is in a recipe for an amulet. Why this word-out of countless words engraved on charms, talismans, and tablets from the ancient world-survived is a mystery as well. Why do stage magicians not shout, for example, "Abrasax!" or "Abalatha!" Why abracadabra?

f you're looking for magical words, you really can't do better than abracadabra! No one really knows what abracadabra means, if it ever meant anything. Its earliest mention is in a recipe for an amulet. Why this word-out of countless words engraved on charms, talismans, and tablets from the ancient world-survived is a mystery as well. Why do stage magicians not shout, for example, "Abrasax!" or "Abalatha!" Why abracadabra?