Contents

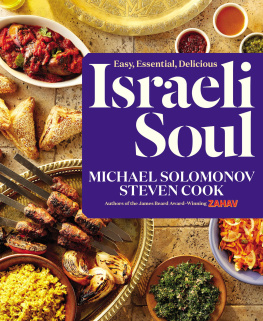

Copyright 2018 by Michael Solomonov and Steven Cook

Photographs copyright 2018 by Michael Persico

Photograph on by Rafael Ben Ari/Dreamstime

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, NY 10016.

hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Solomonov, Michael, author. | Cook, Steven (Restaurateur), author.

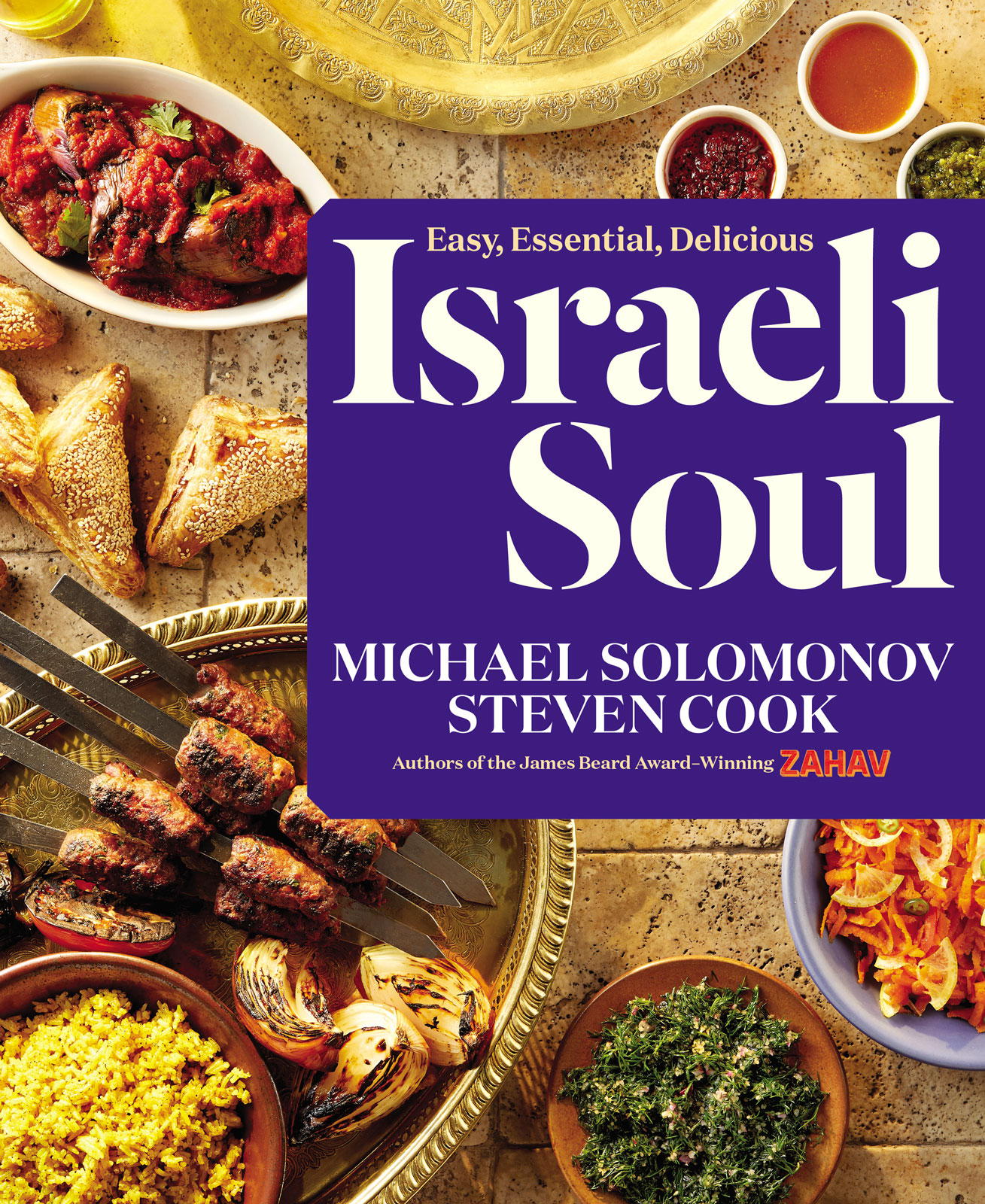

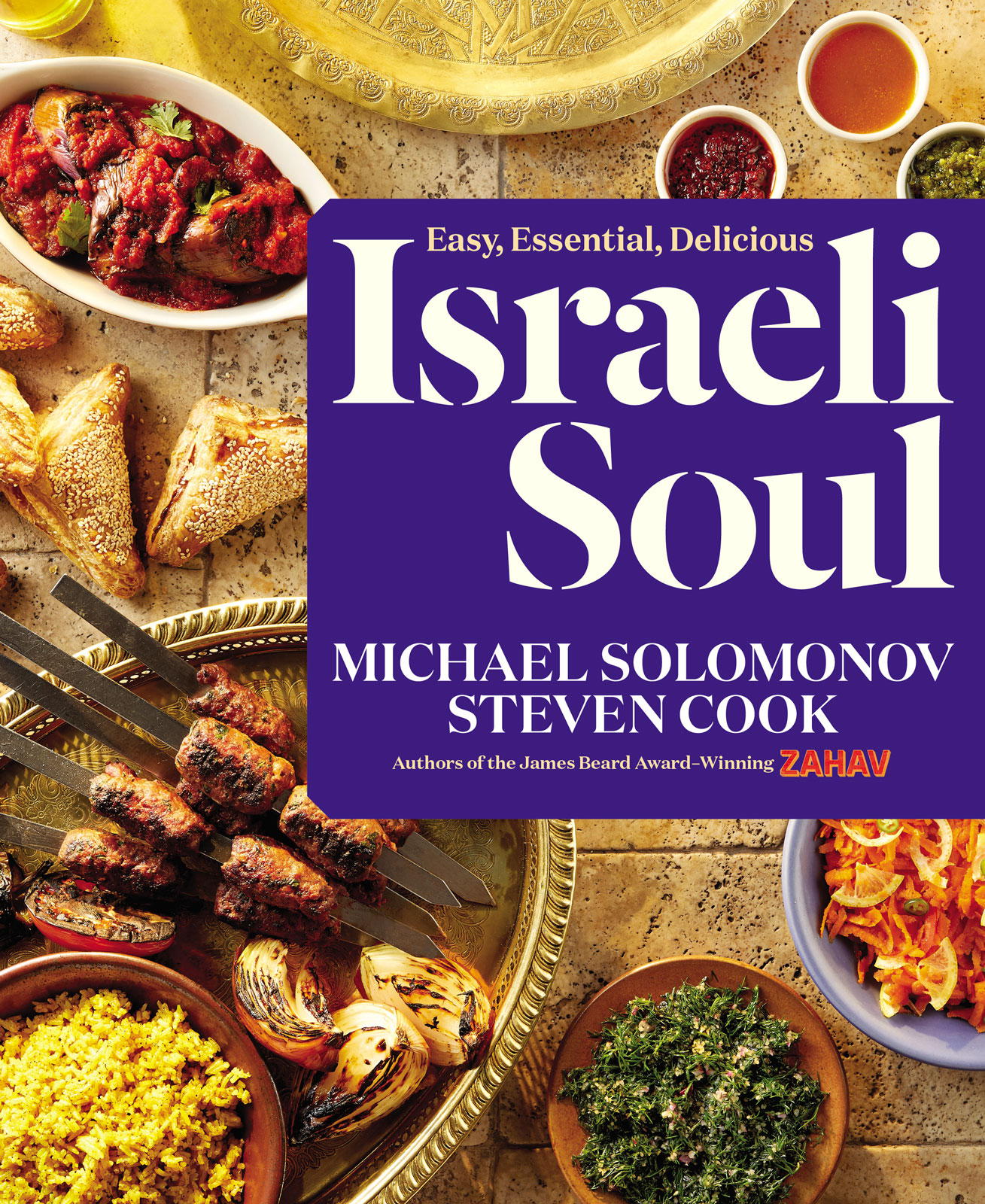

Title: Israeli soul : easy, essential, delicious / Michael Solomonov, Steven Cook.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2018] | A Rux Martin book.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018017712 (print) | LCCN 2018021734 (ebook) | ISBN 9780544971271 (ebook) | ISBN 9780544970373 (paper over board) | ISBN 9781328633453 (special ed)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, Israeli. | Kosher food. | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX724 (ebook) | LCC TX724.S636 2018 (print) | DDC 641.595694dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018017712

Produced by Dorothy Kalins Ink, LLC

Art Direction by Don Morris Design

Recipe Editor: Peggy Paul Casella

v2.1018

To Evelyn Solomonov, Susan Cook, and Laurel Rudavsky

A mother understands what a child does not say

Jewish proverb

Contents

Endpapers: Old City, Jerusalem: Muslim Quarter

Title pages: Ripe pomegranates, Galilee; the Mediterranean at Caesarea

Dedication: Jerusalem

Introduction: Hills of Galilee, Fishing at Akko Map illustration by Don Morris

Acknowledgments: Juice seller, Tzfat

Last page: Olives at Haim Rafael, Tel Aviv

Endpapers: Ancient olive trees, Galilee

Introduction

By the time you read this, Israel will be seventy years old and Zahav, our Israeli restaurant in Philadelphia, will be ten. For ten years weve been calling Zahav a modern Israeli restaurant, but that phrase has never felt particularly apt. After all, theres nothing modern about cooking pita in a wood-burning oven or kebabs over a charcoal grill.

And yet, Israel is a modern country, formed within the lifetime of some of its citizens. Weve been puzzling our way through this contradiction for the last decade. There is a common misconception that Israeli food equals Middle Eastern food. But this is a vast oversimplification that obscures a remarkable story. The soul of Israeli cuisine lies in the journey these foods have taken to the ends of the earth and back, to be woven together in a nascent culture that is both ancient and modern.

It is not just the food of pre-Mandate Palestine, a cuisine that, in any case, was already familiar to the Jews of Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. Nor is it simply the collected recipes of European, Balkan, and North African Jews returning to their ancestral homeland.

For two millennia, Jews have been wandering the earth, embracing the cultures and cuisines of their local hosts, adapting them to their religious and dietary needs, and transmitting the results at each stop along the way. The establishment of Israel in 1948 created a repository for all of these traditionsand a place for them to evolve in strange and wonderful ways.

For us, Israeli soul is sabich, the now classic sandwich of fried eggplant, hard-boiled egg, and the mango pickle amba that developed in Israel from the Sabbath breakfast traditions of Iraqi Jews. It is rugelach, the Ashkenazi pastry, here treated to the Arabic practice of saturating pastries in syrup. It is borekas, the stuffed savory pastries whose flaky dough made its way from Spain, through the Ottoman Empire to Bulgaria, and finally to Israel, where they are now a national obsession.

Like America, Israel is a product of migration. The vast majority of Israelis are only a few generations removed from a completely different life, in a completely different place. Food is a bridge that connects them to their heritageand to each other.

What is the taste of home? Can the memory of childhood be captured in a single bite? How soulful and satisfying is the dish that made its way from the Diaspora to be reborn in Israel? There is a Hebrew expression, ldor vdorliterally from generation to generation. It is the framework on which the survival of the Jewish people has been built for thousands of years, assuring that our values and traditions will outlive us. Our friend and farmer Mark Dornstreich (of blessed memory) used to say that its impossible to be a first-generation farmer. It takes longer than a few years to establish a fruitful relationship with the land. Maybe its the same with restaurants. A ten-year-old restaurant like Zahav is practically geriatric in America. In Israel, it is a toddler.

The parents of Rachel Arcovi, owner of the Hadera restaurant Opera, moved to Tel Aviv from Yemen in 1911. The family lived among immigrants from all over, and Rachels mother learned to make Ashkenazi specialties like kugel, tzimmes, and gefilte fish, which she cooked alongside the Yemenite staples she had learned from her own mother. Her family moved north to Hadera in 1936, sustaining itself any way it could, often by working in orchards or packing plants. In 1974 Rachel took over Opera, a struggling coffee house, which continued to struggle. Her son and his friends, well aware of her gifts as a home cook, encouraged her to use those talents and expand the menu. Forty-three years later, Opera is an institution supporting three generations (and counting).