Contents

This counter-culture revelation of slack or redundancy in our present society proves that one can live off the waste of an affluent majority.

Charles Jencks

acknowledgments

I want to thank Amanda, for putting up with Saturdays in the shop, sawdust in the living room, and life with a guerilla. You are my first reader, my best design critic, my inspiration, and my support.

Thank you to my parents, Fran and John, for supporting my education, teaching me responsibility, instilling a solid Protestant work ethic, and selling me that Corolla for a comically good price. Thank you especially to my mother for her persistent lessons in grammar, however fitfully they may have been absorbed.

Thanks to my siblings and siblings-in-law (Spence, Ellie, Sara, James, and Jane) for their encouragement, legal assistance, design help, copyediting, material donations, and absorption of various discarded furniture prototypes over the years.

Thanks to the fine editors, designers, and staff at Storey Publishing for believing in my story and making this book a reality. Thanks also to Kip Dawkins and his assistant Marcie for the beautiful photographs, and to Kelley Galbreath for designing the book. A special thanks to Philip Schmidt, who first contacted me to feature one of my designs in his book, PlyDesign, and went on to e-mail editors on my behalf and to edit this book for clarity, content, and coherence.

And last, thank you to all the teachers I have had over the years. They taught me about writing, aesthetics, art, architecture, design, carpentry, and ethics. In chronological order: William Jones, Juan Castro, Albert Knight, Robert Goll, Salahuddin Choudhury, Timothy Castine, Hunter Pittman, Christopher Pritchett, Eugene Egger, Paolo Soleri, David Tollas, Mark Melonas, Seth Scott, Andrew Freear, Daniel Wicke, Johnny Parker, Steven Long, John Marusich, Sara Williamson, Cynthia Main, Blake Sloane, John Preus, Tadd Cowen, and Theaster Gates Jr.

Preface

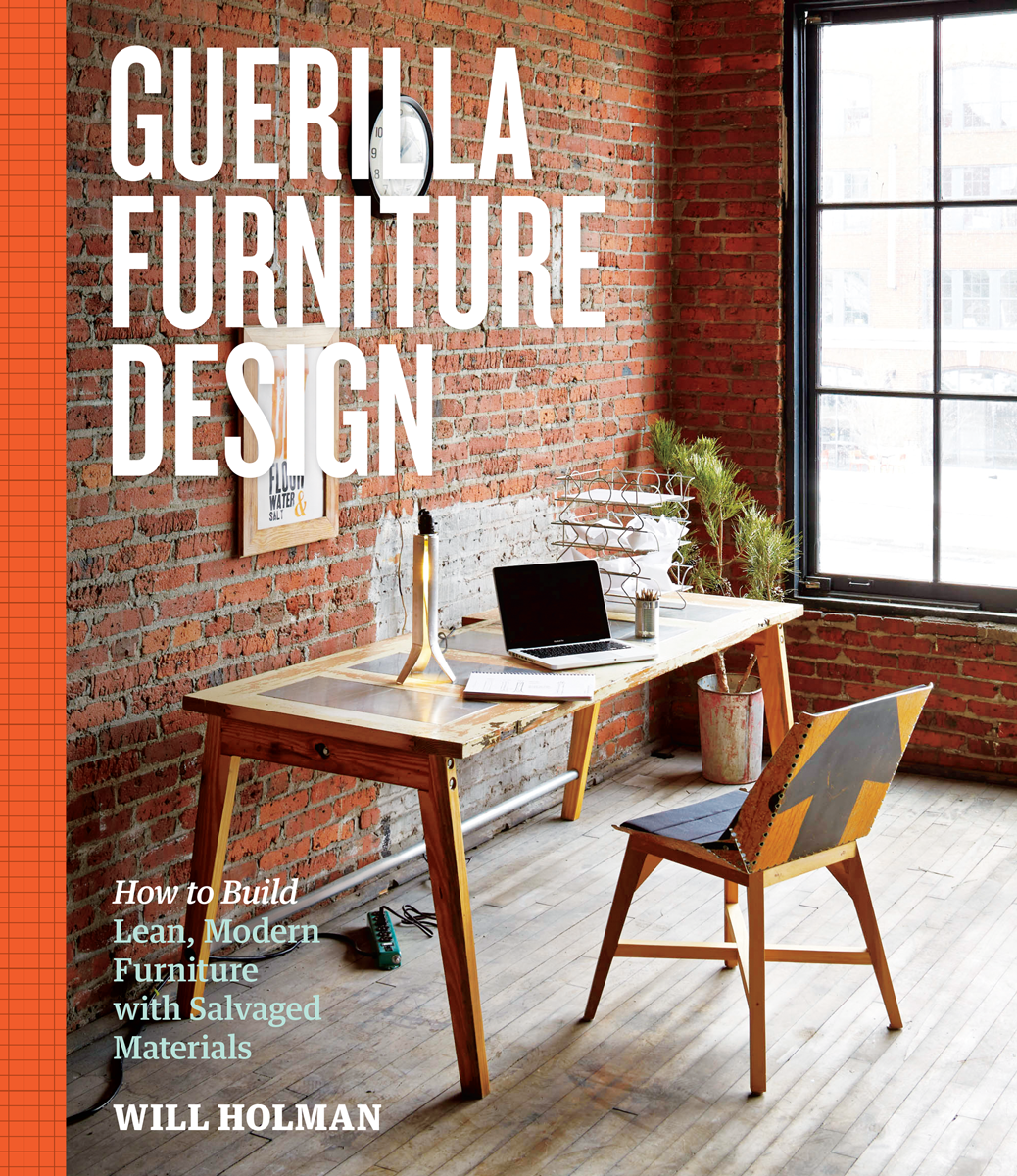

Guerilla design is a set of tactics for building lean, modern furniture out of salvaged materials.

U.S. Army Field Manuals are handbooks for military personnel, published by the Department of Defense. Since World War II, hundreds of titles have been published, including civilian-friendly topics like first aid and wilderness survival. Each manual breaks down complex concepts into manageable pieces, illustrated with simple black-and-white diagrams.

The term guerilla Spanish for little war was invented in the early nineteenth century. In modern usage, guerilla describes both insurrectionary warfare and insurgent fighters themselves. Such fighters are tough, resourceful, and adept at living off the land.

Guerilla design, as described in this manual, is a set of tactics for building lean, modern furniture out of salvaged materials. These techniques are explained generally and then illustrated with a series of case studies, sorted by material: paper, wood, plastic, and metal. Each project is presented in detail, with the assumption that materials and methods will be adapted to conditions in the field.

Introduction

The Education of a Guerilla

Never design anything that cannot be made.

Jean Prouv

I graduated with a degree in architecture from Virginia Tech in May 2007. In June, I packed a van, moved home, and spent a restless summer unsuccessfully searching for work in Baltimore. In August, I put a backpack in the backseat of my 98 Corolla and drove west. I arrived in Cordes Junction, Arizona, one week later.

For the next year I lived at Arcosanti, an experimental community an hour north of Phoenix. Founded in 1970 by Italian architect Paolo Soleri, Arcosanti is a prototype arcology, a dense urban system designed to produce its own food and energy. Eager to learn, I worked in the construction department, welding and pouring concrete, expanding the city. The wide-open country was gorgeous, the people warm and welcoming. I spent my Saturdays rooting around Arcos boneyard, home to 40 years worth of construction debris, scrap metal, scaffolding, and old cars. Dragging fragments back to the workshop, I welded pieces together to create furniture for my co-op apartment.

In the summer of 2008 I headed back to Baltimore, straight into the nascent headwinds of the Great Recession. I spent the next year working at a custom cabinetry shop. At night, I sent out rsums and designed my own projects, hoping the economy would rebound. Architecture firms were devastated by the housing collapse, work was slow, and nobody was hiring. I put aside my architectural dreams for a time and concentrated on developing my woodworking skills, tutored by the master craftsmen at my job.

First Sign. This is my first attempt at road sign furniture, at Arcosanti.

In the spring of 2009 I applied to the Rural Studio. Founded in 1991 by Auburn University professors Samuel Mockbee and D. K. Ruth, the Rural Studio is an architectural design-build laboratory in Hale County, Alabama. I was accepted into their Outreach program, figuring I could wait out the recession for one more year. The studio was (and still is) engaged in a long-term research project the 20K House meant to address the lack of decent low-income housing in the rural South. After eight months at the drafting board, my teammates and I built the ninth 20K House in about 50 days. Our client moved in at the end of June and parked himself on the porch, sitting in a rocking chair I made out of construction scraps.

20K House. MacArthur Coach sits on the porch of his 20K House in Faunsdale, Alabama.

School over, I looked for jobs across the South in New Orleans and Birmingham and back in Baltimore. Nothing came. I managed to rustle up some renovation work around the small town of Greensboro, Alabama, where I was living, spending weeks scraping and repainting the old tin roof on an antebellum home. In late summer I got a job with YouthBuild, a local nonprofit that taught trade skills to young folks (coupled with GED classes) and paid them a small stipend for doing work around the community. That year we built a big vegetable garden, bordered by a fence made of old road signs from the county dump. On the weekends I tinkered with bending extra signs into chairs.

YouthBuilds grant was cut in June 2011. I was out of work and in the wind, again. This time, I pointed the Corolla north, to Chicago, with a tiny U-Haul in tow. But salaried jobs were hard to come by, even in the big city, so I patched together a freelance career building furniture, writing articles about woodworking, teaching design to teenagers, and working for an artist renovating a group of derelict buildings on the South Side. Many of my friends, co-workers, and former classmates were in the same boat, hustling in a gig economy where steady work seemed increasingly difficult to find.