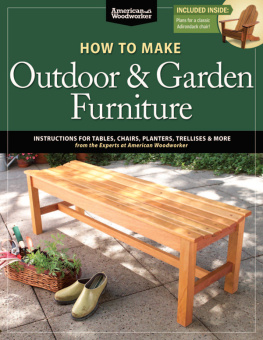

Easy-to-Build Adirondack Furniture

Mary Twitchell

Introduction

Building Adirondack furniture is a time-honored craft. Sturdy and rustic, this furniture can be a beautiful addition to any indoor decor, although its most often used to set the scene outdoors. There, the furniture is subjected to a lifetime of abuse. Yearly it moves from somewhere hidden away (probably dark and musty winter storage) to front-and-center on the summer stage. Now, hour after hour it is beaten on by intense UV light, drenched in driving rains, then fried again in the summer sun. Through it all, the furniture patiently endures ever handsome, ever inviting, ever lasting. To survive summertime abuse and the semiannual ritual of being dragged into and out of storage, outdoor furniture must be sturdy, rugged, and well built all qualities that epitomize Adirondack pieces.

This bulletin contains instructions for building an Adirondack chair, matching footstool, companion side table, and Westport chair (an ancestor of the modern-day slatted Adirondack chair). Each project will take the moderately skilled carpenter less than a day to fabricate; for the beginner, maybe a weekend. However, none of the cuts is difficult, and no special tools are required.

Choosing the Right Lumber

When furniture is set outdoors, its wood is exposed to wet weather, damp soils, and insects all the conditions that stress joints and cause wood to rot. Naturally decay-resistant woods such as western red cedar, cypress, redwood, and oak are therefore the smartest building materials. These species, however, are expensive; Douglas fir and southern yellow pine are less decay resistant but when painted they make attractive and durable substitutes.

Pressure-treated lumber will last for 20 years (much longer than untreated woods), but if its sawdust gets into your eyes, the experience will be extremely painful. You may also object to putting your skin in constant contact with chemically treated wood. A compromise solution is to cut your chairs legs and stringers (they come in contact with the ground and are therefore the most susceptible to rot) out of pressure-treated lumber, then construct the rest of the piece from untreated stock.

Regardless of wood species, choose your lumber carefully. Avoid boards that cup, twist, or bow. They will make construction much more difficult, if not impossible. Choose boards with as few knots as possible. Sometimes you can avoid the knots by judicious cutting, other times not. Before final placement of any precut piece, check the two surfaces and place the better surface face up.

For strength and a sense of aesthetics, choose straight, sturdy boards with as few knots as possible.

Fasteners

When considering what type of screws to use, focus on the galvanized, brass, stainless-steel, or zinc-coated varieties. Stainless-steel drywall screws have a Phillips head and are easily driven by a power drill fitted with a Phillips-head driver. These screws wont corrode or rust, but they are expensive.

Bits used to drill pilot holes should be of the same diameter as the solid part of the screw (that is, minus the threads). Drill pilot holes for all screws. If a screw is countersunk close to a boards edge, the wood is likely to split; predrilling the holes prevents this. Should the wood split, turn over the board or cut a replacement piece.

If the screws will show on your final piece, pay close attention to their placement. Screw heads should create a consistent pattern. For the slats, recess the screws " (1 cm) from the sawed ends and use two screws per end.

Whenever larger surfaces adjoin (stringers to legs, for example), use three screws in a triangular or diagonal pattern so that the screws enter the wood in different grains. For greater strength, screw from both sides of a joint.

Glue

Use a waterproof carpenters wood glue; this is yellowish, and it will strengthen wood joints. Apply glue to adjoining surfaces. If youve applied too much, it will ooze out the edges when the boards are screwed together. With a wet rag, remove the excess before it dries. If it is allowed to dry, the excess glue will have to be chipped off and will leave a stain on the wood.

Finding a Construction Surface

For Adirondack furniture assembly, work on a smooth and level surface; otherwise the pieces wont sit squarely when finished. If youre building on your garage floor, for instance, check first whether its floor slopes toward a floor drain.

Sanding

The directions here call for sanding the pieces after theyve been cut but before they are assembled; because of the slat construction, it is very difficult to sand the wood once the chair has been screwed together. Sand first with a coarse-grained paper (120 grit), then with a fine grit (220).

A 1" 3" 4" (2.5 7.6 10.1 cm) sanding block wrapped with sandpaper is easy to use if youre hand-sanding; a palm sander or belt sander will make the process quicker.

Finishing Tips

The finish you choose may depend in part on which wood you choose. For decay-resistant woods (redwood, cedar, cypress, oak), use stains and varnishes; they let the natural grain of the wood show through. Softwoods (pine, fir) have knots and imperfections, which will look better if painted.

Wood sealers maintain the woods natural appearance. Apply three coats with a brush or roller. Wait until the previous coat has dried before applying the next.

Stains, on the other hand, impart a brown or gray color to the wood. Apply these finishes with a rag.

If you choose to paint your furniture, prime all surfaces before assembly. When the project has been completed, apply two coats of high-gloss or enamel paint. Dark green, gray, and white are the traditional colors, but the primary colors red, blue, and yellow are also becoming popular.

The Adirondack Chair

The Adirondack chair has graced lawns for more than 90 years. Originally called the Westport chair (it was designed by Thomas Lee for his home in Westport, New York), the chair has always been associated with life at the great camps (the summer residences of the Rockefellers, the Vanderbilts, and their peers) in the Adirondack Mountains of upper New York State.

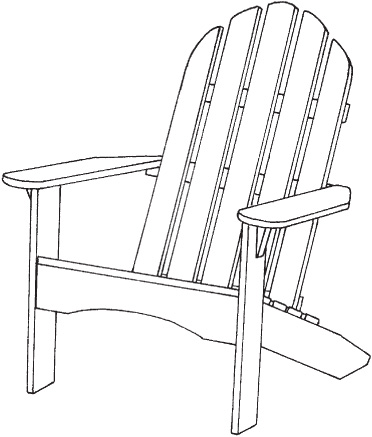

The design of the chair is unique. With its five-slatted, sloped back, its wide arms, and its steeply angled seat, the Adirondack chair is instantly recognizable. Its design is simple, unfettered, and amazingly attractive with straight clean lines and an alluring low profile a sharp contrast to its wobbly modern-day counterpart of twisted aluminum and frayed plastic webbing.

The Adirondack chair is a classic element of our rural landscapes. It is sturdy, simple, and attractive and will last many, many years.

Materials and Tools for the Adirondack Chair

Tools

Tape measure

4 (1.2 m) level

Power drill with Phillips-head driver, or Phillips-head screwdriver

Drill bit for pilot holes

Circular saw or ripsaw

1" (2.5 cm) chisel

Rafters square

Sanding block, palm sander, or belt sander with assortment of sandpaper (coarse to fine)

Framing or rafters square

T-bevel

Hammer

Jigsaw