Build a Pole Woodshed

by Mary Twitchell

CONTENTS

The mission of Storey Publishing is to serve our customers by publishing practical information that encourages personal independence in harmony with the environment.

Cover design by Carol J. Jessop (Black Trout Design)

Copyright 1980 by Storey Publishing, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this bulletin may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages or reproduce illustrations in a review with appropriate credits; nor may any part of this bulletin be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other without written permission from the publisher.

The information in this bulletin is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Storey Publishing. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. For additional information please contact Storey Publishing, 210 MASS MoCA Way, North Adams, MA 01247.

Storey books and bulletins are available for special premium and promotional uses and for customized editions. For further information, please call 1-800-793-9396.

Printed in the United States

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Twitchell, Mary

Build a pole woodshed / by Mary Twitchell

A Storey Publishing Bulletin, A-42

ISBN 0-88266-216-3

Introduction

More and more people are turning to wood as a primary or secondary heating fuel, and as this number increases, so too does the sophistication of our wood stoves/furnaces, and our knowledge of wood heat. By late autumn there are few homesteads, particularly in the northern rural areas, which arent obscured by their seemingly infinite cords of split wood cords stacked outside or in sheds to season. Properly seasoned wood is as important a part of the woodburning process as a well-constructed stove or a safe installation.

Most woodburners now know that green wood can be as much as 65 percent water. This means that in burning a piece of green wood, as much as 1200 BTUs per pound (or 1/8 the potential heat value of the log), is lost in evaporating the moisture. In addition, wet wood is much more difficult to ignite and to keep burning. Worst of all, it produces more creosote which creates a potential fire hazard.

Wood Must Dry

Getting the full heat value from a piece of wood is very simple. The wood must be allowed to dry, and preferably for two years. (Seasoning times vary with the climate; in the desert wood dries much more quickly, in colder wetter areas drying may take two years or more.)

Over this two-year period, the green wood dries at various rates. Much of the moisture evaporates very quickly. In the first three months the seasoning is half complete and the fuel value is 90 percent of what it will be when thoroughly dried (evaporation also depends on temperature and humidity). In the next six to nine months, the wood is reasonably dry; in two years it will be as dry as it will get.

If you have invested time, energy, and money in a wood stove installation, its foolish to forego a further savings by burning green wood. It requires no work to let wood season, and in the process you are increasing its heat value; the wood will be lighter, ignite better, and produce less smoke and fewer sparks.

The following pages outline various ways to speed the seasoning process from no-cost methods of stacking the wood properly to building a low-cost, pole-built storage shed.

Preparing Wood for Storage

After a tree is felled, it should be bucked to length, then split. Splitting is easiest when the wood is green and preferably frozen. Wood can be left round if under six inches in diameter. If the logs are of greater diameter, they should be split to prevent decay and accelerate the drying process. Since wood dries more rapidly along the grain, it is necessary to break the water barrier the bark to let this process occur. Splitting also increases the surface area which speeds up drying.

It is essential to split birch and alder or they will rot. Dont be shy about splitting wood; you can always use kindling. In addition, splitting reduces the sizes to be burned, and wood stoves/furnaces burn cleaner and more efficiently if fed splits of no more than six inches in diameter.

Open-Air Stacking

Indoor or basement storage may seem the most logical way to dry wood, but you will probably have to contend with dirt and insects. There will be fewer problems if the wood is stored outdoors with a weeks supply stacked in the basement or on an enclosed porch for easy access.

Wood piled outdoors against an exterior wall of the house is conveniently located, and you wont have to negotiate cellar stairs with armloads of wood. It also keeps the dirt and insects outside, but the exterior house walls will cut down on air circulation to the pile, water may drain off the house onto it, and it may dry very slowly, if at all.

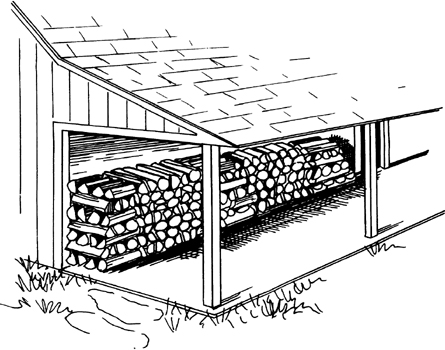

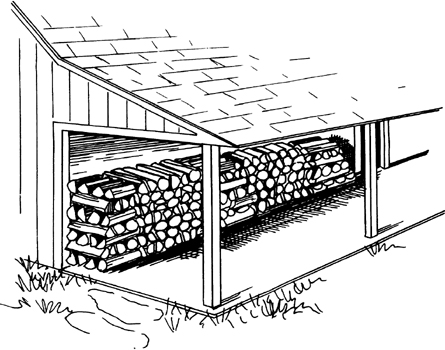

Wood stacked on a porch for seasoning.

If you have a concrete patio, wood can be piled there. Otherwise, locate the pile within a reasonable distance of the house. If the pile is located too far away, getting to it will be difficult in winter; if located too close, insects may be a problem, fire a hazard, and good air circulation more difficult to achieve.

Avoid damp places or depressions where water will collect after a rainfall or during the spring runoff. Loose soils dry the fastest; clayey soils the slowest. The wood should have maximum exposure to the sun and wind. The best location is on a hilltop or knoll where there are more air currents.

Consider the prevailing winds. The longer dimension of the pile should be exposed to the summer winds.

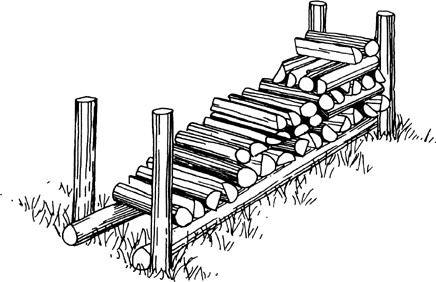

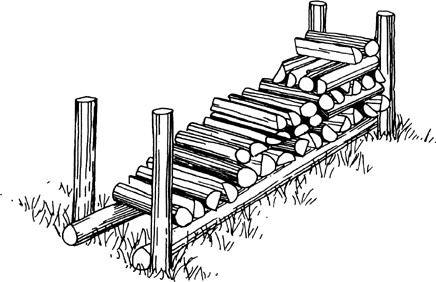

Lay down two stringers (poles of three to four inches in diameter) running the length of the pile. Anything can be improvised for support (stones, 2 x 4s, metal pipes) as long as it raises the pile about four inches off the ground to prevent decay and rot. Place the stringers a foot or so apart, and leave plenty of space between the piles.

The stringers can be of any length, but if youre curious about the number of cords of wood that youve cut, they should be eight feet long. At either end, drive in stakes to prevent the pile from collapsing. Cut them so that when driven in they are four feet high. Stack the splits so that they straddle the stringers.

Stacking wood on stringers speeds curing.

It is a real annoyance to have a pile tip over in the middle of winter. As a precaution, pile the last two splits in every row crosswise and tilt them slightly towards the pile to give it more stability.

The splits will air-dry more quickly if, after the first layer, the entire next layer is laid criss-cross, and the direction of the splits alternated with each tier until the pile starts to wobble. Leave the splits stacked criss-cross for three months, then restack them in the normal, parallel fashion.

Wood without bark will dry faster, but stripping it is impractical. Strip elm of bark to prevent the further spread of Dutch elm disease. This bark should be burned or the beetle will continue its nefarious activities once the weather warms.