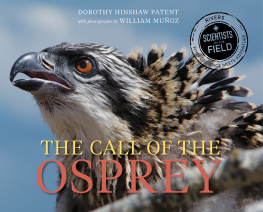

Text copyright 2015 by Dorothy Hinshaw Patent

Photographs copyright 2015 by William Muoz

All images by William Muoz with the exception of the following: pp. (second and third) by Ashton Clinger.

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

Design by Ellen Nygaard

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Patent, Dorothy Hinshaw, author.

The call of the osprey / Dorothy Hinshaw Patent ; with photographs by William Muoz.

pages cm.(Scientists in the field)

Audience: Ages 1014.

Audience: Grades 7 to 8.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-544-23268-6

1. OspreyMontanaJuvenile literature. 2. OspreyEffect of mining onJuvenile literature. 3. MercuryBioaccumulationUnited StatesJuvenile literature. 4. PollutionEnvironmental aspectsJuvenile literature. 5. Wildlife conservationUnited StatesJuvenile literature. 6. ScientistsJuvenile literature. I. Muoz, William, illustrator. II. Title. III. Series: Scientists in the field.

QL696.F36P379 2015

598.9'3dc23

2014016090

eISBN 978-0-544-67218-5

v2.0615

Prologue

On a cold day in March of 2013, Bill Muoz, a photographer, and I drive up to the Riverside Health Care Center, a nursing home and skilled nursing facility just east of Missoula, Montana. Were meeting Erick Greene and Heiko Langner, scientists from the University of Montana, and Matt Young, their assistant. We shiver as we face into the bitter wind and head for the tall metal pole at the edge of the parking lot. On top of the pole is a flat platform with the remnants of an osprey nest and an extension on one side that holds a video camera. The three men are there to reactivate the camera after the long winter in anticipation of the April arrival of Iris and Stanley, a pair of ospreys that nested there the previous season. At least they hope Iris and Stanley will show up, since they proved to be outstanding parents. Ospreys mate for life, but a lot can happen in the seven to eight months that the birds spend thousands of miles south, in Mexico or beyond. Stanley and Iris had attracted many fans around the world to their webcam, and those people were eagerly awaiting the stories that would come with the new breeding season.

Erick and Heiko at work with the camera.

This webcam and another one south of Missoula are a boon to the long-term Montana Osprey Project, research the scientists have been carrying out since 2006, along with Rob Domenech, a fellow scientist. This study focuses on what has been the largest Superfund site in the country, an area that includes a 120-mile stretch of the Clark Fork River running from the mining town of Butte, Montana, to the former Milltown Dam a few miles east of Missoula. The Superfund project aims to remove the millions of tons of mining waste contaminated with heavy metals and to restore the natural environment. The scientists are using ospreys, birds that consume fish they catch in waterways near their nests, to evaluate the types and amounts of contaminants in the river. By analyzing samples of blood and feathers from osprey chicks being raised in twenty nests along the Clark Fork and its tributaries, the researchers can tell which toxic metals still linger in the system and where they are concentrated. They also use the project as an opportunity to educate the public about the natural world through the two webcams and visits by students and summer campers to the nests.

Erick and Heiko climb aboard the platform that the big red and white roofing truck will lift up to the camera. After donning safety harnesses and helmets, the two men are hoisted up as Roy Van Ostrand, the truck driver, expertly guides the platform over to the nest pole. Working on the camera in the cold Montana weather is not a pleasant chore, as the men need to use their bare hands to adjust the camera. Bill and I shiver as we crane our necks to watch the scientists patiently labor to make sure the camera is working well.

The roofing truck lifts Erick Greene and Heiko Langner up to check on and clean the video camera that will bring the lives of the ospreys into homes around the world.

Its clear that the birds will have a lot of work to do fixing up their nest this year.

Once they return to the ground, its our turn for a lift. Im afraid of heights and had felt a bit leery as I watched the platform sway in the wind, but Heiko waves at me to come over. I hesitate, but he calls out with a smile, Come aboard, its part of the project. Besides, its fun. Okay, Im coming, I answer, and join the men.

Bill and I don the harnesses and hard hats and up we go, soaring beside the swiftly churning Clark Fork River below, where the ospreys catch fish. We hunker down inside our coats, trying to avoid the cold wind as it gently rocks the platform. Despite the swaying, Im not at all afraid; Heiko was rightthis is fun. Roy expertly swings the platform up close to the empty nest, and I peer down to examine whats left from last year. Im surprised to see little more than an almost flat surface of compacted material with some sticks encircling the diameter. I can see that the birds will have a lot of work to do to build a proper nest here once again, and I look forward to watching them, thanks to the webcam. Roy swings the platform down again and I exit quickly, rubbing my icy hands together in a vain attempt to warm them.

Im glad to get back to my car, where I turn on the heat right away. Once home, I check my e-mail, and theres already a message from Erick, with attached photos of me and Bill on the platform titled High on Life. I know Im going to enjoy being part of this project.

Dorothy and Bill go up to take a look at the Hellgate osprey nest.

CHAPTER ONE

THE GREAT FISHER

Its a warm, sunny afternoon in early May at the Riverside Health Care Center, where Erick Greene greets a group of students from Hellgate High School in Missoula. They have come to learn about ospreys, birds whose giant nests decorate the tops of dead trees and nesting platforms along the shores of rivers, lakes, and seas across the country and around the world, including in Europe, northern Asia, and Australia.

These young ospreys are growing up amid the mountains of Montana.

Erick Greene tells the high school students about ospreys.

Spreading the Word

The scientists work hard to spread the word about ospreys and the dangers of pollution in several ways. The visiting students are part of the flagship program of Missoulas Watershed Education Network (www.montanawatershed.org), a nonprofit offering young people information about the ecology of waterways in western Montana. The scientists are also part of the Birds-Eye View Education Program, which carries out summer programs for children and adults that teach them about the effects of mining activities, the life along the river, river restoration, and similar topics. Since these efforts have begun, thousands of young people and adults have learned about the environment along the river where they live.