I first came into contact with ospreys in the 1970s when I was a teenager undertaking some voluntary work with the Scottish Wildlife Trust at Loch of the Lowes. Now, as the Scottish Wildlife Trusts chief executive, I am delighted to have been asked to write a foreword to this inspiring account of the bird believed to be Scotlands oldest osprey, a summer resident at Loch of the Lowes.

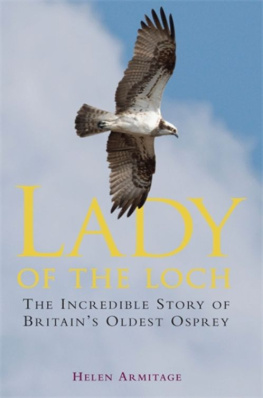

The return of the osprey to Scotland is a major conservation success story and represents a beacon of hope as we strive to rebuild our beleaguered biodiversity and battered ecosystems. Helen Armitage reveals the astonishing life of one of our most impressive and high-profile birds in a tale that involves surviving twenty round trips of 6,000 miles to West Africa and raising forty-eight chicks. It is the story of a bird that became a member of a Perthshire community and whose successes and tribulations have been followed by people all over the world.

The book is also a tribute to all those who have played, and continue to play, a part in ensuring the survival of Scottish ospreys, particularly those who have spent so many nights on osprey-watch, guarding nests against egg thieves and other vandals. The conspicuous devotion of these frontline, unpaid enthusiasts to the conservation of Scotlands wildlife and wild places has had a significant influence on my own development, and instilled in me a huge respect for conservation volunteers.

The return of the osprey, and attendant viewing and interpretation opportunities created by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and the RSPB, has delighted and inspired generations of people and helped to build much needed support for Scotlands conservation programmes. Helen has produced a valuable insight into the history of the osprey in Scotland and I am very confident that this intimate and absorbing account of the bird that became known as Lady will inspire even more people to delight in the intrinsic value of our native wildlife and to support nature conservation.

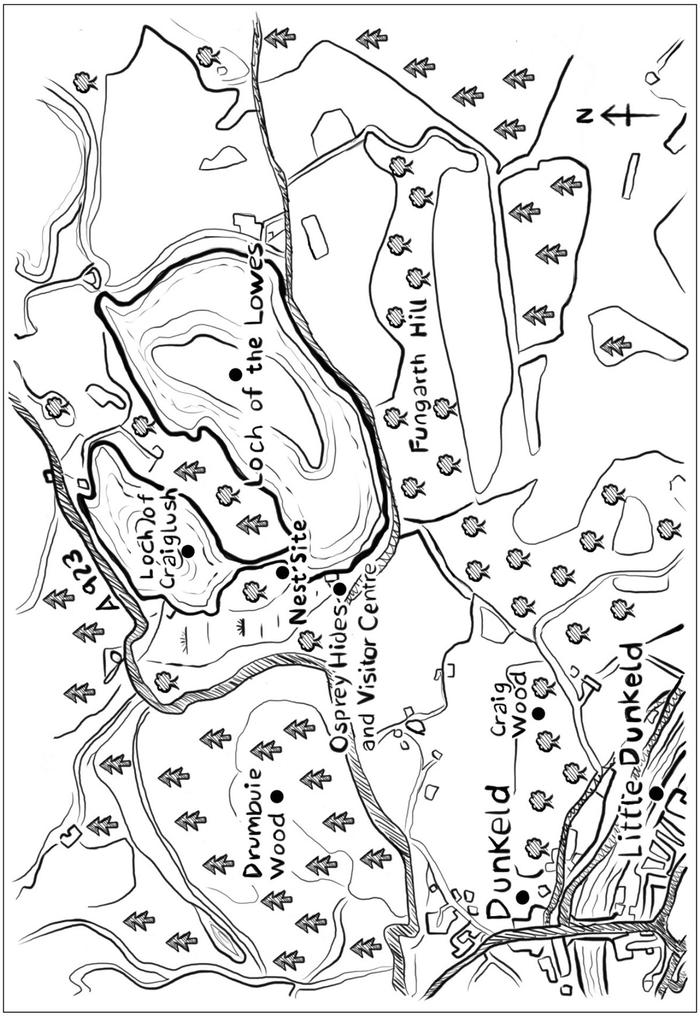

To everything there is a season, and a time and purpose. For Lady, Britains oldest breeding osprey, summers end was her time to leave her Scottish nesting grounds. It marked the close of the ospreys annual breeding season and the start of their long flight south to autumn and winter in West Africa. That year, 2009, proved no exception to a routine that Lady had established over almost two decades: she would depart the Scottish Wildlife Trusts Loch of the Lowes nature reserve in late July or early August to undertake her three-thousand-mile autumn migration.

By the middle of August, Lady was no longer to be seen on her scenic nest overlooking tree-lined, reed-fringed Loch of the Lowes, attending to her almost fully grown chicks, or in flight above its fish-laden waters, or perched in one of her favourite trees in the surrounding woodland. Soon confirmation came from the Lowes reserve, where Lady had arrived in March, that their female osprey had indeed departed that year for tropical Senegal or Gambia. This was Africa at an ecological crossroads, the countries straddling a transition zone that supported a mosaic of habitats suited to a diverse range of birds, with the ospreys and Lady among them.

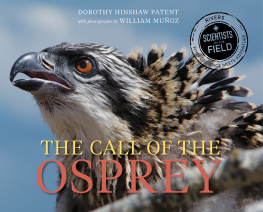

As she had done each year for almost twenty years, Lady had spent the spring and summer of 2009 on her nest at Lowes. From the reserves visitor centre it was easy to see the shambolic-looking latticework of fat sticks, as capacious as a double bed, set sixty-foot high atop a blue-green Scots pine. From that familiar nest, in which she had raised a record number of chicks, she had stretched her wings one last time in August. Lifting herself skyward, she had likely moved off with powerful wingbeats to fly high above the woods that encircled the loch. For anyone watching from the Lowes observation hides or out walking or working in the surrounding woods, fields or hillsides in that corner of Perthshire, she would have been hard to miss: a big bird, flashing by in a gleam of white and chocolate brown, with a distinctive five-foot wingspan. Sharp eyes or strong binoculars might have spotted her identifying highwaymans mask, the band or stripe of dark brown feathers that extended around her bright lemon yellow eyes to the back of her head, or the characteristic female breastband of her upper chest, a wide necklace of heavily speckled feathers that lay just above her white chest.

But now that she had gone, what the eye could not see the heart still grieved for: Ladys absence hung heavy, as it did every year at Lowes after she abandoned Scottish skies for Africa. She had earned a reputation over the years as a characterful bird and had captured the public imagination. For years, she and her ever-increasing osprey family had excited interest, curiosity and passion, locally, nationally and, indeed, internationally. In Lowes nearest town of Dunkeld, the ninth-century capital of the new nation created by the union of the Scots and Picts, everyone followed her progress with interest, discussing her regularly in the streets and cafs. Locals had known of Lady for years; some had even participated in the annual osprey watch to protect her eggs from collectors each breeding season, day and night.

They looked forward to her presence in Lowes skies each spring and summer, swooping, soaring high on fixed wing over the ever-changing waters of the loch, and delighted in watching her flight, direct and purposeful, high above the reserves dense, encircling woodland where she had nested since 1991. Lady was a practised parent: she had spent many a long day building, breeding, defending, feeding, as if her work were never done. Then perching motionless, yet eternally watchful, on a lofty lookout post.

Whether circling, flapping, hovering or still, Lady had an enviable birds eye view of the Perthshire landscape. The county over which she flew sits at the heart of mainland Scotland and includes the heather-clad peaks of the Trossachs the Highlands in miniature. It is an ancient land, comprising the early Celtic earldoms of Atholl, Breadalbane, Gowrie, Strathearn, Mentieth and Balquhidder . Lowes itself lies in the earldom of Atholl, once the area of Clan Duncan, who supported Duncan I, murdered by Macbeth. When the line became extinct in the early thirteenth century, the region and the earldom reverted to the Crown until the mid-1400s, when James II of Scotland bestowed the title on a Stewart of Balvenie. Later Queen Anne raised it to a dukedom. The seat of the earls and dukes of Atholl is the turreted Blair Castle, which dates from the thirteenth century, and is close to the Grampian Mountains, a strategic location on the route north to Inverness. It was once a threatening, dangerous place, but is now a landscape of wild, natural beauty.

Dunkeld is typical of Perthshires numerous age-old settlements. An attractive town, with a long and dramatic history, it was made the seat of the Scottish primacy in AD 851 by Kenneth MacAlpin, first king of Scots, and was once the ecclesiastical centre of Scotland. A battle raged around Dunkeld Cathedral during the Jacobite uprising of 1689 but now it is a peaceful place, with lawns that slope down to the river. The town lies several miles north of Perth in the hilly, rugged countryside of the southern Grampians, nestled in a valley, enclosed by woody crags and watered by the Tay. The magnificent lochs, mountains and glens make it a haven for ospreys.