Lady Nijōk - Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine

Here you can read online Lady Nijōk - Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Tuttle Publishing, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine

- Author:

- Publisher:Tuttle Publishing

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lady Nijōk: author's other books

Who wrote Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

APPENDIX I:

The Historical Background

During the thirteenth century effective political control of Japan moved more and more firmly into the hands of the Bakufu, the Military Government, established at Kamakura in 1192 by Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-1199), even though sporadic attempts continued to be made at intervals by those connected with the Imperial court at Kyoto to regain some semblance of political power. Exiled to Izu after the fall from power of the Minamoto clan under his father, Yoshitomo, Yoritomo had taken up arms against his rivals, decisively defeated them, and set up the headquarters of the Military Government at Kamakura away from the influence of the Capital. From there, under the Minamoto and Hojo families, it was to govern the country for the next 160 years. Yoritomo had in fact set the pattern for military rule in Japan for 650 years with the gradual erosion of Imperial power, so that by the end of the Kamakura period the Emperor was left with merely ceremonial functions.

By the end of the thirteenth century also, the Bakufu had acquired complete control of the national income. Gradually the receipts from the manorial estates of the Imperial court and from those of the court nobles had been alienated to the Military Government through the constables and stewards whom it appointed over these estates, so that by the second half of the century the Imperial court was in straitened circumstances, dependent in fact on a few families of court nobles to defray much of its day-to-day expenses. By the end of the thirteenth century, the economic power of the Bakufu itself was also showing signs of strain as a result of the rise of powerful local families and the drain on the Exchequer due to the threat of the Mongolian invasions.

All through the thirteenth century the powerful military families, such as the Minamoto and Hojo families, continued their struggle for control of the Military Government, while members of each family strove among themselves to obtain the most influential positions. An incident recorded in Towazu-gatari illustrates this struggle. Lady Nijo reports the visit of the two High Commissioners of the Military Government, Hojo no Tokisuke and Hojo no Yoshimune, to the Retired Emperor Go Saga on his deathbed to express the sympathy of the Bakufu. Six days later she mentions that Tokisuke's house in Kyoto had been attacked and he himself had been killed, but gives no further details. What had happened was that, on orders from Kamakura, Hojo no Yoshimune had attacked and killed his fellow Commissioner, who was, it was alleged, planning revolt. The victim was a son of the ex-Regent Hojo no Tokiyori and elder brother of the Regent at the time, Hojo no Tokimune, who saw in his elder brother a formidable rival in the struggle for power.

At the time of Lady Nijo's visit to Kamakura in 1289, the executive power of the Military Government was exercised in the name of the Regent (Shikken), Hojo no Sadatoki, who had succeeded to the post in 1284 at the age of fourteen. Supreme power was, however, actually in the hands of the Governor-general (Kanrei), Taira no Yoritsuna, but he was soon afterwards, in 1293, to fall from power and suffer execution for his usurpation of authority. Increasingly powerful at Kamakura at this time also was Ashikaga no Takauji, who was in the next generation to give the final blow which was to destroy the military power of the Hojo family and establish at Kyoto the Ashikaga Military Government which was to endure for 237 years.

The original basis of the power of the Military Government was in the functions of the Generalissimo (Seii-tai-shogun or Shogun) whose duty it had been in more ancient times to put down revolts in the country, especially among the barbarian aborigines, against the authority of the Emperor. On the establishment of the Kamakura Government, Yoritomo had been granted the title of Shogun in 1192, but after the assassination of Yoriie in 1204 and Sanetomo in 1219, the Hojo family had exercised this authority with the title of Regent, and in 1252 for the first time an Imperial prince, Munetaka, the son of the Retired Emperor Go Saga, was appointed to this post as a figurehead and as a convenient hostage in the hands of the Military Government. On her visit to Kamakura, Lady Nijo saw the return to Kyoto in disgrace of Munetaka's successor, his son Prince Koreyasu, Shogun from 1286 to 1289, and the arrival of a new Shogun (1289 to 1308), Prince Hisaakira, son of the ex-Emperor Go Fukakusa. The prince's mother was Fujiwara no Fusako, one of Go Fukakusa's consorts, who appears in Towazu-gatari under the name of Lady Mikushige from her post in charge of the Imperial wardrobe.

During her visit Lady Nijo also met the all-powerful Governor-general, Taira no Yoritsuna, becoming very friendly with his second son, the lord of Iinuma, Taira no Sukemune; they found a common interest in poetry. She describes her meeting with the Governor-general; how unimpressive she thought him as he came tripping in, his official robes too small for him, to stand beside his much more stately-looking wife. Later she records her sorrow on learning that both father and son had suffered death at the hands of the Regent. She also tells about the Regent, Hojo no Sadatoki, and finds little to admire in him; all the orders of the Military Government were issued in his name, but he was too obviously only a figurehead, overshadowed by his more powerful retainers. In general she viewed the Kamakura scene with the detachment of one accustomed to the more cultured way of life of Kyoto, respected by all as "somone from the Capital," while she was most careful not to become too deeply involved in the affairs of the Kamakura administration. She expressed her views on it quite frankly. Indeed, the chronicle of the time, Masukagami, which borrows extensively both in matter and form from Towazu-gatari, is careful to tone down her adverse criticism of the Kamakura government and of the warrior classes (buke) in contrasting them with the court nobles (kuge).

At Kyoto during the whole of the period all the forms of government continued to exist just as they had done in the heyday of the Imperial power in the Heian period three hundred years before. Court nobles still held the titles of the offices prescribed in the Taiho Code of a.d . 702: Chief Minister (Dajodaijin), Ministers of the Left, Right, and Centre (Sadaijin, Udaijin, and Naidaijin). Above them was the more recently created office of Kampaku (Imperial Adviser). The Kampaku at the time of Lady Nijo's story, referred to as the Great Lord Konoe, was Takatsukasa no Kanehira (1227-1294), fourth son of Konoe no Iezane and founder of the Takatsukasa family. His eldest son, Takatsukasa no Mototada (12471313), also held the post of Imperial Adviser. Kanehira's elder brother, Konoe no Kanetsune (1210-1259), known as Prince Okanoya, is also mentioned. Kanehira resigned his post in 1287, entered religion in 1290, and died in 1294. Below the Ministers were several Great State Counsellors (Dainagon), their deputies (Gon Dainagon), State Counsellors of Middle Rank (Chunagon), and a host of counsellors and officials of lower rank. Besides these were the officers of the guards, the Bodyguards of the Right and Left (Sakon-e and Ukon-e), the Military Guards (Sahyoe and Uhyoe), and the Gate Guards (Saemon and Uemon). The principal officers were General (Taisho), Lieutenant General (Chujo), and Major General (Shosho).

Control of the Imperial Court by the Military Government was effected by balancing against each other two rival lines of the Imperial succession. In accordance with what was already a long-established custom, a prince was selected to succeed to the throne in infancy and was usually prevailed on to abdicate at adolescence. There were therefore often several ex-Emperors, with the title of Joko, living in Kyoto, each with his own court complete with ministers and officials, some of these ex-Emperors having taken vows of religion and living as religious with the title of Ho-o. The other princes as a general rule entered religion as children and became prelates of important Buddhist temples.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

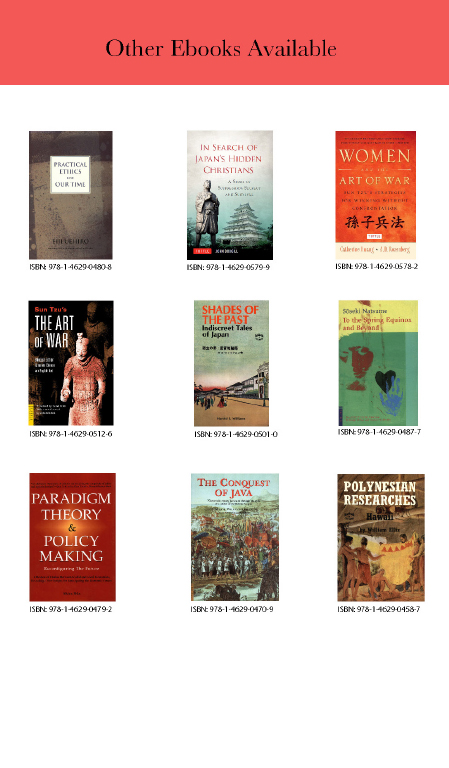

Similar books «Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine»

Look at similar books to Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Lady Nijos Own Story: The Candid Diary of a Thirteenth-Century Japanese Imperial Concubine and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.