Contents

Introduction

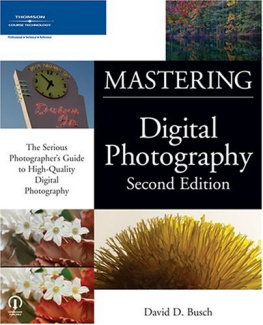

Digital photography has evolved rapidly, leading to an exciting revolution in the capture of wildlife images. New technology has inevitably brought new challenges, notably how to extract the best from digital cameras, and how to tackle the steep learning curve associated with processing images once downloaded to the computer. It is the latter process that perhaps challenges most, provoking a common unwillingness to embrace new technology. The fear of change is a human emotion shared by many, and I include myself in this. It took me two years to jump into the digital arena, but when I look back now, that feels like two wasted years.

A poor picture cannot be transformed into a great one. However, a good image can be enhanced to one that really shines. It is worth remembering the popular saying rubbish in, rubbish out. Using poor techniques in the field with the attitude that the important part of making great photographs lies in your prowess with the computer is a recipe for taking pictures that could have been very much better.

The terminology within digital photography of bits, bytes, megabytes, histograms and so on can be offputting. In this book, I aim to unravel this jargon and show you what it means, and to present an explanation of what I do alongside the resulting pictures. While the first few chapters explore the technology you will use and the techniques you will commonly employ in taking pictures, the later chapters on processing images on your computer are far more personal; they are written from my own experience, and illustrate what I do, rather than showing the only way to do things. This is important to recognise because you will find by talking to different photographers that no two photographers work with images on the computer in quite the same way. Although the basic processing techniques will be the same, both workflow (editing and processing steps) and adjustments in Adobe Photoshop are likely to differ. The simple fact is that there are both many software programs for editing and many different ways of carrying out the same adjustment in Photoshop. You may have already developed your own way of working; this is good, but you may also learn some different techniques from this book.

The many software programs available for editing images include well known names such as Breeze Browser, Apples Aperture and those from Adobe that include Lightroom and Photoshop. Designed specifically for photographers they offer the ideal platform for editing and processing RAW images. I have chosen to illustrate the steps I take in the editing process using Photoshops Bridge and Adobe Camera RAW. The reason for this is that it is likely at some point that you will have to or want to use Adobe Photoshop. Having said this Adobes Lightroom is now a viable alternative offering the photographer all the tools required to organise and process images and so you will find a section within this book exploring the basics of Lightroom. The basic tools whether in Photoshop, Lightroom or other image processing software remain roughly the same, the interface may look different but all do the same thing, therefore whatever application you decide to use, you should still be able to follow my explanations and apply them to your own workflow.

If you are new to digital photography and you are learning how to process your images, you will soon discover the majority of adjustments you make are down to using your judgement, and such adjustments will soon be second nature. By remembering this, the often daunting prospect of remembering various processes will feel less arduous.

The ability to manipulate images, and even the ability to create images, has created quite an animated debate within the wildlife photography world. Some photographers have emerged who describe themselves as photographic artists, producing beautiful images that are heavily manipulated, and often the combination of two or more images. On the other side of the fence, are the purist photographers who want to stay as true to nature as possible. The problem lies with those that create images and then attempt to pass them off as being true to nature. This generates an atmosphere of distrust, and the viewer becomes confused and cynical about whether a particular image can be believed. While photographers can generally identify these created images, the viewing public may lack the insight required to spot them.

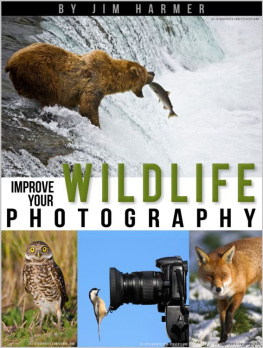

The author with a Grizzly Bear in Alaska. This Grizzly Bear came so close, I could hear its heavy breathing, and perhaps the bear could hear my heart pumping faster and faster! It was a special moment, if not a little unnerving. However, just out of shot a guide was crouched ready with a flare in the event that the bear came any closer.

(Picture courtesy of Anita Stokes)

A similar issue exists with regard to captive subjects. For many professionals, the opportunity to photograph a captive animal or one in a controlled environment is a means to an end, and can save many days or weeks in the field. Indeed, most professionals cannot justify extended periods in pursuit of subjects that may at the end of the day fail to repay the time spent in the chase. But purists condemn photographs of captive animals, and most people would always prefer an image of a creature taken in the wild, in its natural surroundings.

Both images of captive animals and those created with a computer have their place, and they can help to enrich the world in which we live with new and exciting pictures. Such images should always be clearly identified as of captive origin or manipulated. Those that publish images, knowing they are not natural but presenting them in a genuine context, are perhaps as much to blame as the photographers themselves. However, I would like to think that the majority of wildlife photographers feel a duty to declare when an image is a montage or when the subject has been photographed in a controlled or captive situation. Of course, context is everything; people generally accept that images used in advertising have no need for such disclosure. It is only important when images are used in an editorial context and passed off falsely as the real thing. In this book, I have not included such images, with a few notable exceptions where I have given an explanation in the caption.

My main purpose in writing this book has been to show how I go about taking and dealing with digital images, and to try and convey the immense pleasure I derive from being out in the wild, making pictures. Being so close to a surfacing whale as to be able to smell its breath, and watching in awe as tens of thousands of Starlings wheel in unison over a city skyline are two spectacles I have recently enjoyed with camera in hand, and on both occasions I put down the camera in order to soak up the atmosphere. My message is that you should never lose sight of what you are photographing and its welfare, and if you do put your camera down to enjoy that special experience, just make sure you dont miss that exceptional shot!

CHAPTER 1

Getting started

Digital photography is fun, best illustrated by the phenomenal growth in sales of digital cameras worldwide. We no longer have to wait for hours, days or weeks to see our results they are instant. Not only that, but rather than relying on someone else to develop our film, we can now do it ourselves, and take the image, crop it or correct it if necessary in short we have total control.