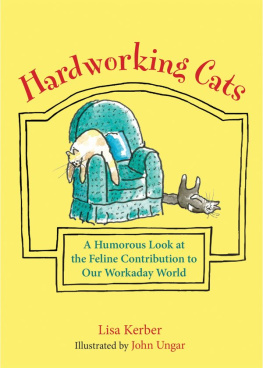

Seafurrers: The Ships Cats Who Lapped and Mapped the World

Copyright 2018 by Philippa Sandall

Illustrations copyright 2018 by Ad Long unless otherwise noted in the , a continuation of this copyright page.

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or online reviews, no portion of this book may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The Experiment, LLC | 220 East 23rd Street, Suite 600 | New York, NY 10010-4658

theexperimentpublishing.com

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and The Experiment was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been capitalized.

The Experiments books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk for premiums and sales promotions as well as for fund-raising or educational use. For details, contact us at .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sandall, Philippa, author.

Title: Seafurrers : the ships cats who lapped and mapped the world / Philippa

Sandall and Ad Long.

Description: New York, NY : The Experiment, [2018] | Includes bibliographical

references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017047334 (print) | LCCN 2017056969 (ebook) | ISBN

9781615194384 (ebook) | ISBN 9781615194377 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Cats. | Human-animal relationships. | Seafaring life.

Classification: LCC SF442 (ebook) | LCC SF442 .S26 2018 (print) | DDC

636.80092/9--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017047334

ISBN 978-1-61519-437-7

Ebook ISBN 978-1-61519-438-4

Text design by Sarah Smith, based on designs by Clare Forte and Ky Long

Cover design by Sarah Schneider

Front cover illustration by Ad Long; cover photo Robert Bahou | offset.com

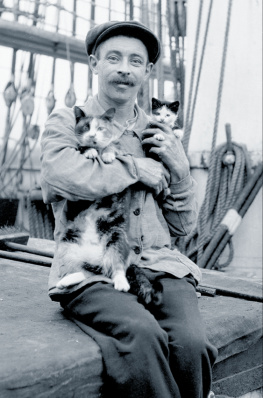

Back cover photo, Sydney, circa 1910, by Samuel Hood/Australian National Maritime Museum

Manufactured in China

First printing April 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Preface

W hile the many extraordinary exploits and achievements of the seafarers who lapped and mapped the world are well documented, those of their indispensable pest controllers, shipmates, and mascots are not, apart from a few celebs you will read about here. These famed felines include the intrepid Trim, who circumnavigated Australia with Matthew Flinders; the invaluable Mrs. Chippy, who weathered Antarctic blizzards while keeping watch on Ernest Shackletons Endurance; and the redoubtable Simon of the Amethyst, who maintained his pest-control duties day in, day out despite being seriously injured in the Yangtze Incident. Hence this incidental seafurring history, a somewhat flotsam-and-jetsam maritime miscellany drawing on letters, diaries, memoirs, newspaper reports, and photographs to shed new light on life on the ocean waves in the days of sail and steam. We felines favor the oral tradition of storytelling, as you may be aware, so to help me pull this together and put it down on the page, I roped in the indispensable services of a scribe (Philippa Sandall) and illustrator (Ad Long). The views and commentary, of course, are all my own and are signposted throughout: According to Bart.

I am from a seafurring family. My name, Bart, is a nod to our family hero, the courageous Portuguese explorer and navigator Bartolomeu Dias de Novais, who was given instructions to sail southwards and on to the place where the sun rises and to continue as long as it was possible to do so in 1487. First to round the Cape of Good Hope was his claim to fame. (European and as far as we know should probably be added to this.) Dias sailed out of Lisbon, headed down the west coast of Africa, rounded the Cape, and made it into the Indian Oceangateway to the Orient and its richesand then safely back home. Round trip: sixteen months and seventeen days. There were plenty of rough patches, but homeward bound the Cape took the cake. Cabo das Tormentas (Cape of Storms) was what he wrote on the charts. Back in Lisbon, armchair traveler King John II claimed naming rights and plumped for Cabo da Boa Esperana (Cape of Good Hope), in hot anticipation of pepper profits and the lucrative spice trade with India. But that was not to be, at least not for another decade and another king.

Christopher Columbus stole the limelight in the interim. He headed west for the spices of the East in 1492 and found the New World. What that really means is he sailed across the Atlantic, dropped anchor in the Bahamas, staked the Castile Crowns claim, called the fiery chile that the locals ate pepper, and to his dying day never admitted he hadnt found what he was looking for. As an unknown and unkind critic aptly put it: When he started out he didnt know where he was going. When he got to the New World he didnt know where he was. And when he got back to Spain he didnt know where he had been.

Vasco da Gama knew exactly where he was going on his passage to India in 149798, and Portugal got its sea route to the East Indies and a monopoly on the profitable spice trade for the next hundred years or so, until the determined emergence of Dutch maritime power, seemingly from nowhere, changed the game again.

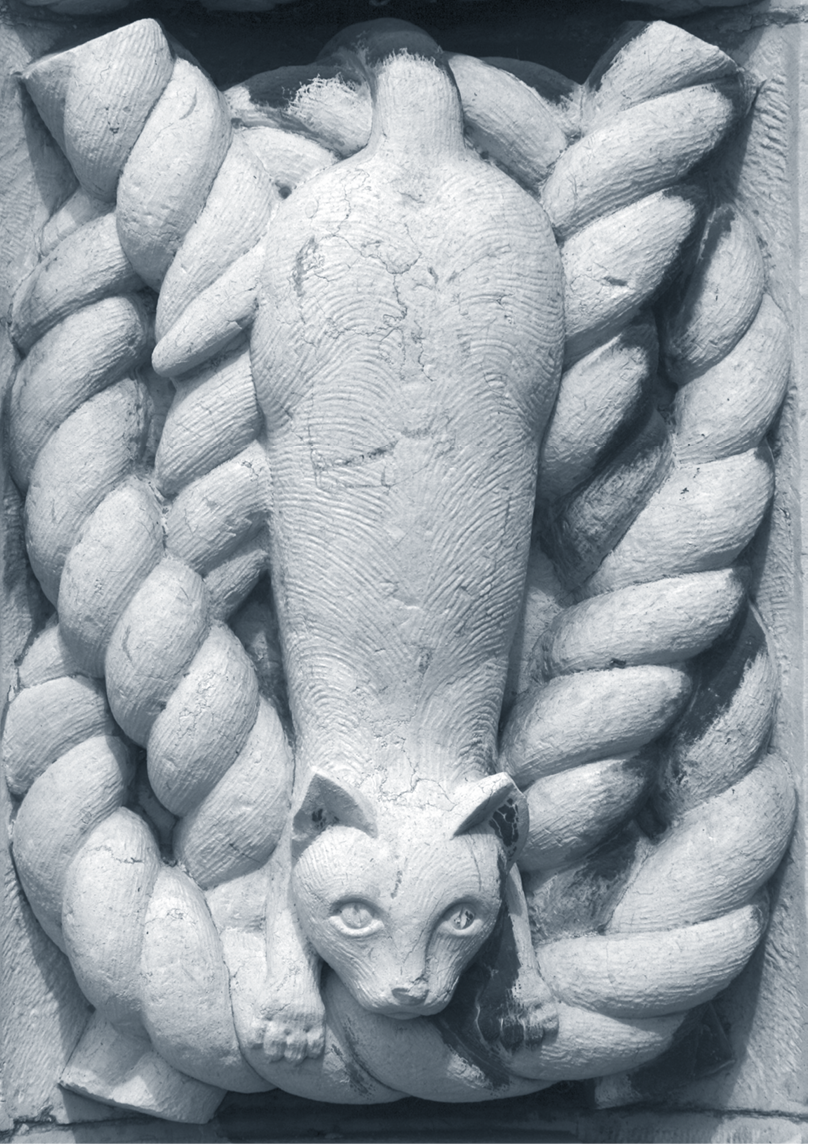

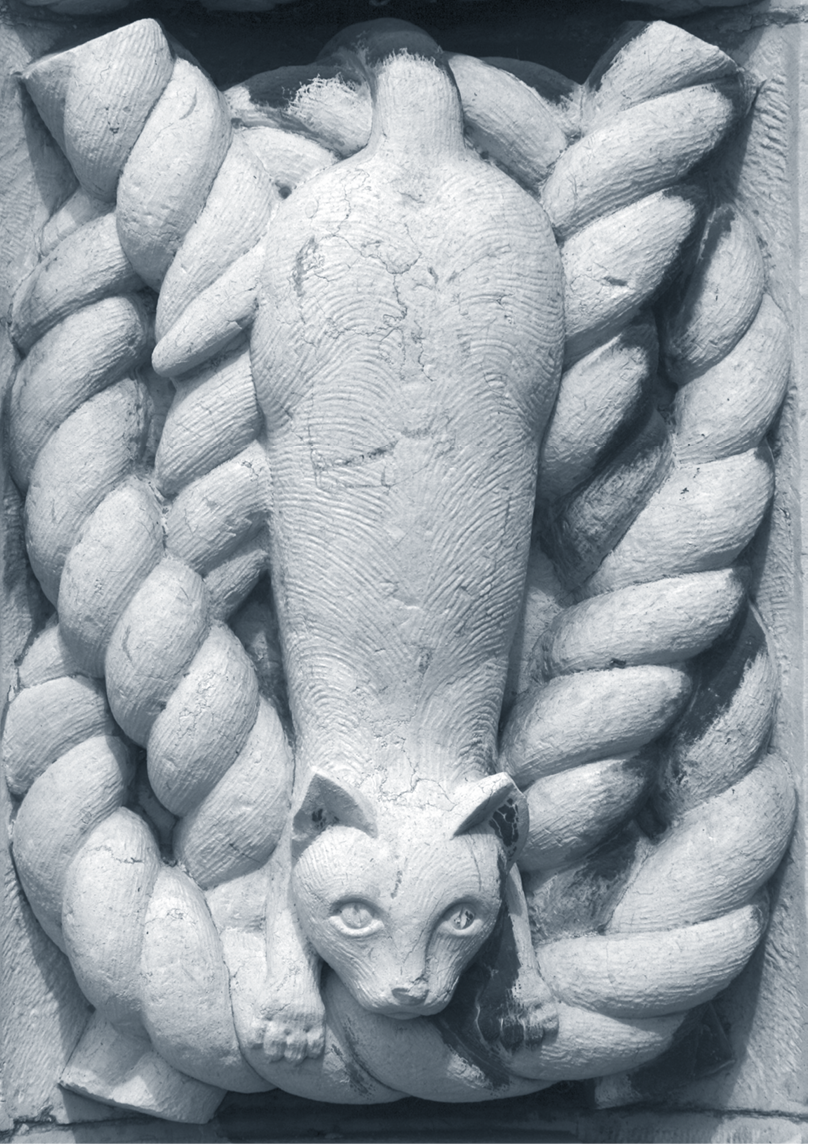

But not one of themDias, Columbus, or da Gama, nor the explorers and traders who followedcould have done it without the onboard protection against pests for their provisions and cargoes that their able-bodied seafurrers tirelessly provided. How do we know ships cats played such a key role? The Portuguese carved it in stone, as you can see on this sixteenth-century decorative column in the cloisters of the Jernimos Monastery in Belm, Lisbon.

A watchful seafurrer stretched out on a square knot, carved on a column of the sixteenth-century Jernimos Monastery in Lisbon. Today, the monasterys west wing houses the Maritime Museum.

A seaman enticing the ships cat up one of the shrouds of Pommern, a four-masted barque

and windjammer operating on the grain trade route between Australia and England during the interwar years, and now anchored behind the land Maritime Museum as a display

Embarking

ACCORDING TO BART

To begin at the beginning, I guess I need to explain how our feline forebears stepped out of the wild and became the sea cats who lapped and mapped the world. It all began some twelve thousand years ago, when Homo sapiens (whom Ill call sapiens from now on to keep it simple) embraced a change that changed everything. They quit their nomadic hunter-gatherer way of life in various parts of the world and, with a natural eye for real estate, picked out prime locations by lakes and rivers with plenty of freshwater to settle down.