ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Friends of cephalopodsboth the forty-one paleontologists who congregated at the 2016 meeting of the Geological Society of America in Denver and the worldwide community of amateur and professional aquarists, rock hounds, and scientistsare some of the kindest people Ive met. Theyre as kind to a ten-year-old who just learned the word cephalopod as they are to a graduate student scrambling for data, and as kind again to a writer tackling her first book. I extend eight armloads of gratitude to all the cephalophiles who have inspired and informed me over the years.

Two electronic homes for tentacle science deserve special mention. FASTMOLL is a mailing list for researchers who study fast mollusks (which means, of course, the cephalopods), and despite their heavy workloads the scientists on the list responded quickly and generously to all my inquiries. TONMO, The Octopus News Magazine Online, is a forum for anyone interested in octopuses (and other cephalopods), amateur or professional. I drank deeply from the resources of this welcoming community.

For sharing their knowledge of the natural world and their enthusiasm for the scientific endeavor, Im indebted to a great many researchersI hope I have remembered them all, and I apologize to any whose names Ive inadvertently omitted. Kathleen Ritterbush offered prompt assistance with every request, no matter how obscure or mundane, and shared more bizarre and fascinating stories than I could fit in the book. Kenneth De Baets was a tremendously helpful correspondent throughout the research and writing process. Neil Landman and Peg Yabocbucci welcomed me warmly into the cephalopod circle, and along with Dirk Fuchs, Christina Ifrim, and Jakob Vinther, they did their best to straighten out my sketch of the evolutionary tree. Louise Allcock, Sasha Arkhipkin, Matthew Clapham, Jerzy Dzik, Eric Edsinger-Gonzales, Bret Grasse, Kiana Harris, Megan Jensen, Christian Klug, Dieter Korn, Isabelle Kruta, Adrienne Mayor, Heike Neumeister, Scott McKenzie, Neale Monks, Roy Nohra, Andrew Packard, Richard Ross, Isabelle Rouget, Jocelyn Sessa, Martin Smith, and Vojtch Turek all patiently answered my abundant questions despite the demands of their own work. Many of these generous people also took the time to read and correct portions of the manuscript. Any mistakes that remain despite their efforts are entirely mea culpa.

The cheerful guidance of my agent, Lydia Mod, has helped every step of the book-writing adventure. She always has the best ideas, one of which was connecting this project to editor Stephen Hull at the University Press of New England, whose cogent advice and criticism caused a real book to emerge from a sea of disparate stories. Im also immensely grateful for the hard work of production editor Ann Brash and copy editor Mary Becker. Christine Heinrichss comments on an early draft were both sensible and inspirational, and Yael Kisels incisive feedback throughout the writing process stimulated many crucial manuscript surgeries. Designer Eric Brooks made a book more beautiful than I ever imagined.

Many thanks to the photographers and artists whose creations illuminate the text; my work would be much poorer without theirs. Cynthia Clark took on the lions share of the illustration and responded with heroic patience and humor to my every email. The eyes that peer so charmingly from the evolutionary tree of cephalopods are all hers.

The academic roots of this work owe a great deal to my undergraduate adviser, Armand Kuris, who actively encouraged my octopus obsession, and to my paleontology professor, Bruce Tiffney, who welcomed my term paper about cephalopod evolutionthe zeroth draft of this book, you might say. Later support came from my graduate adviser, Bill Gilly, who introduced me to Humboldt squid, taught me sterile laboratory techniques, and unsnarled my fishing lines.

My fathers help has been instrumental to the whole journey, from setting up my first aquarium to providing project management as I wrestled with this manuscript. Im grateful to my children for happily embracing all things tentacled and for challenging me with questions about fossils, extinction, and when Mom will be done writing her book. As for my husband, he brewed pot after pot of tea, took our darling distractions to the park, and cast a critical eye on text and figures. My gratitude to him is as deep as a spirulids implosion limitmaybe deeper.

The World of the Head-Footed

J et-propelled and flight-capable, iridescent and elastic, squid are a true marvel of nature. Theyre fast: they can swim twice as fast as an Olympic champion, shoot their tentacles out in less time than it takes you to blink, and alter their appearance at literally the speed of thought. Theyre flashy: some grow luminous lures at the ends of their arms, others squirt self-portraits in ink, and their skin creates any color from vivid red to iridescent blue.

Yet most humans dont know a lot about squid. We tend to view them through the lens of either mythology or gastronomy, limiting these wondrous creatures to the role of terrifying Kraken or tasty calamari.

If youre in the first camp, kept up at night by visions of Jules Vernes Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea or Peter Benchleys Beast, then relax and get some sleep. Although giant squid can grow to almost 40 feet, 25 is far more common, and most of that length is in their slender, stretchy tentacles. Whats more, there are no reliable accounts of any squid, no matter how giant, endangering boats or killing humans.

On the other hand, if the only thing you know about squid is whether you prefer them fried in rings or raw with rice, youre not alone.

Swimming Protein Bars

Pretty much every animal that encounters a squid tries to eat it. Even bears and wolves have been known to take advantage of the occasional beach stranding.

The poor things are born delicious. Squid produce huge numbers of offspringfrom hundreds in some species to hundreds of thousands in othersnearly all of which are eaten before they grow up. When they hatch from their eggs, theyre smaller than your fingernail, so Babys First Predators are small too: fish larvae and aquatic worms.

But squid grow quickly, and in a matter of days or weeks those that survive turn the tables. Growing fat on their onetime adversaries, squid start to attract larger predators: seals and seabirds, sharks and whales. The sheer scale of squid consumption is mind-boggling. Scientists once pumped the stomachs of sixty elephant seals from South Georgia and found 96.2 percent squid by weight. Meanwhile, a single sperm whale can eat 700 to 800 squid every day.

Rough luck for the squid. However, it earns them the dubious honor of being named ecological keystones. They start so small, grow so fast, and get so big that they provide abundant food for marine predators of every sizea one-prey-fits-all solution. Thus, many species of squid act as biological conveyor belts, moving energy from tiny plankton up to apex predators. Including humans.

Squid and their octopus and cuttlefish relatives have been caught and eaten by humans for probably as long as humans have

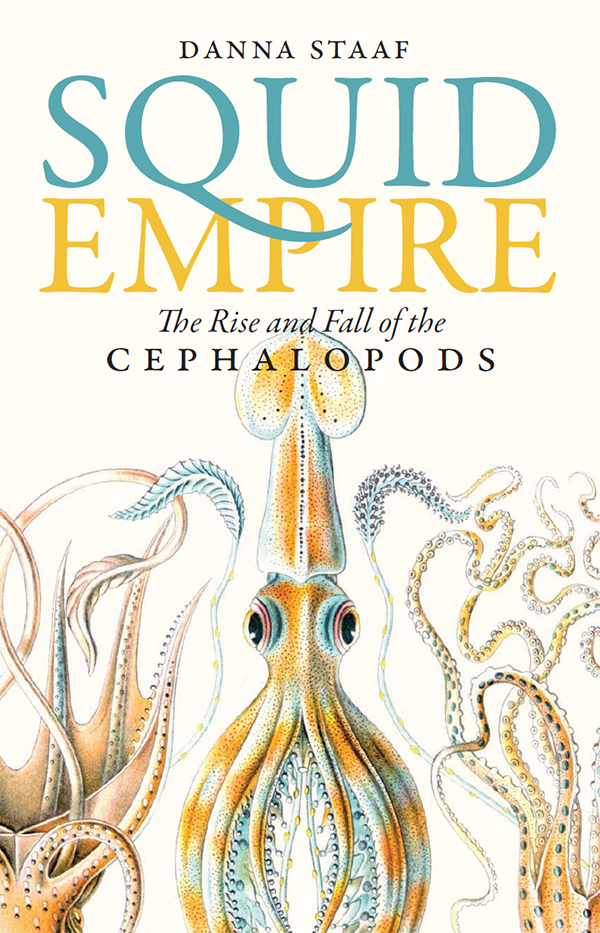

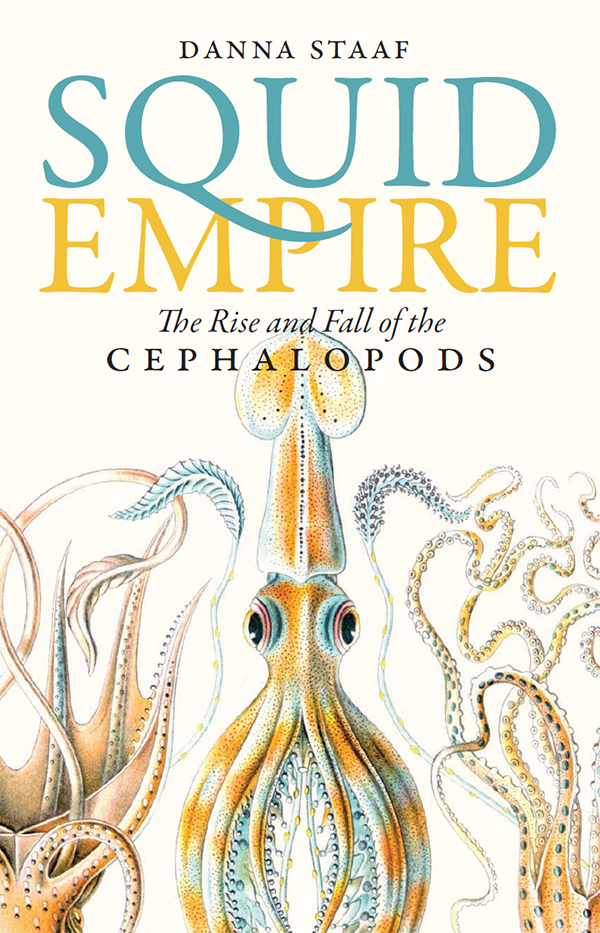

FIGURE 1.1 Humboldt squid can grow up to 2 meters long and spawn millions of eggs. Their size and abundance support the worlds largest invertebrate fishery.

Next page