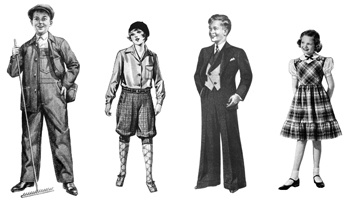

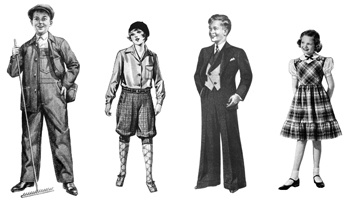

CHILDRENS FASHIONS 19001950 AS PICTURED IN SEARS CATALOGS  Edited by JOANNE OLIAN Curator Emeritus, Costume Collection Museum of the City of New York DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC Mineola, New York

Edited by JOANNE OLIAN Curator Emeritus, Costume Collection Museum of the City of New York DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC Mineola, New York

At Dover Publications were committed to producing books in an earth-friendly manner and to helping our customers make greener choices Manufacturing books in the United States ensures compliance with strict environmental laws and eliminates the need for international freight shipping, a major contributor to global air pollution. And printing on recycled paper helps minimize our consumption of trees, water and fossil fuels. The text of this book was printed on paper made with 10% post-consumer waste and the cover was printed on paper made with 10% post-consumer waste. At Dover, we use Environmental Paper Networks Paper Calculator to measure the benefits of these choices, including: the number of trees saved, gallons of water conserved, as well as air emissions and solid waste eliminated. Courier Corporation, the manufacturer of this book, owns the Green Edition Trademark.

For Amy Rose Copyright Copyright 2003 by Sears, Roebuck & Co. For Amy Rose Copyright Copyright 2003 by Sears, Roebuck & Co.

Introduction copyright 2003 by Dover Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Bibliographical Note This Dover edition, first published in 2003, is a new selection of patterns from Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalogs published between 1902-1950. The catalog images within this book are reprinted by arrangement with Sears, Roebuck & Co. and are protected under copyright.

No duplication is permitted. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Childrens fashions, 1900-1950, as pictured in Sears catalogs / edited by Jo Anne Olian. p. cm. A new selection of patterns from Sears, Roebuck & Co. verso. verso.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-42325-8 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 0-486-42325-5 (pbk.) 1. Childrens clothingUnited StatesHistory20th centuryPictorial works. 2. CostumeUnited StatesHistory20th centuryPictorial works. 3. I. I.

Olian, JoAnne. II. Sears, Roebuck and Company. GT615.C55 2003 . 391'3'097309041dc21 2003043842 Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation 42325503 www.doverpublications.com CONTENTS Introduction What is the use of a book without pictures? asked Alice. Had Sears been available in Lewis Carrolls Victorian England, she would undoubtedly have pored eagerly over the pages of each catalog the moment it arrived.

If a history of American childhood were to be compiled, it could do no better than to be composed of illustrations from the pages of Sears. The ultimate picture book, it also served as a school book in many a farm community. In rural schoolhouses children were drilled in reading and spelling from the catalogue. They practiced arithmetic by filling out orders and adding up items. They tried their hand at drawing by copying the catalogue models, and acquired geography by studying the postal-zone maps. In schoolrooms that had no other encyclopedia, a Wards or Sears catalogue handily served the purpose; it was illustrated, it told you what something was made of and what it was good for, how long it would last, and even what it cost.

Many a mother in a household with few childrens books pacified her child with the pictures in the catalogue. When the new book arrived, the pictures in the old catalogue were indelibly fixed in the memory of girls who cut them up for paper dolls.1 The pages of Sears are to American clothing what Norman Rockwells paintings are to American art. Both convey an idealized image of an optimistic middle class in which happy families went about their lives and domesticity ruled the day. Emblematic of this philosophy was the editorial in Sears Fall 1936 Golden Jubilee catalog: Father and Son! The greatest combination on earth!... Nothing can lick a Dad and his boywhen they hitch themselves up in double harness and pullTOGETHER. And exactly the same thing goes for a Mother and her daughter.

Much can be learned by observing a societys attitude toward its children, who are the visible manifestation of a familys aspirations. In turn-of-the-century America, in what Thorstein Veblen identified as vicarious consumption, parental pride was manifested by dressing ones children as well as possible, even if it entailed sacrifice, so that they might bear witness to the familys well-being. While everyday garb might have been fashioned from the canvas of the covered wagon that had carried them across the plains, in photographs, pioneer children pose solemnly in their starched Sunday best beside the family sod house or before an ornate studio backdrop, poignant testimony to their parents pride and hopes. Hence, it is not surprising to find considerable space devoted to juvenile apparel in the pages of Sears. Not until the late nineteenth century was it common in the United States to think of children as a distinct class of the nations population, meriting and requiring special treatment For most of modern history, the social and psychological meaning of childhood was vague; a child was, for all practical purposes, simply a small adult. The change in American thinking appeared only as children became a minority of the population,2 transformed into mouths instead of productive hands.

In earlier times, children lacked the freedom enjoyed by modern-day youngsters. Restrictive clothing made them look like miniature adults, which indeed they were. One of the first influences on modern-day thinking toward children was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who dealt extensively with their education and physical well-being in Emile, written in 1762. Rousseau recommended that The limbs of the growing child be free to move easily; there should be nothing tight, nothing fitting closely to the body, no belts of any kind. The French style of dress, uncomfortable and unhealthy for a man is especially bad for children. The best plan is to keep children in frocks for as long as possible, and then to provide them with loose clothing, without trying to define the shape, which is only another way of deforming it.

Their defects of body and mind may be traced to the same source, the desire to make men of them before their time. While Rousseaus pedagogic philosophy was to prove an important influence on education, less attention was paid to his theories of dress. For the next hundred years mothers continued to dress their children as small adults, in the most picturesque fashion possible, with little regard to comfort or freedom, prompting such observers as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a pioneer in the nineteenth-century womens rights movement, to remark, The most casual observer could see how many pleasures young girls were continually sacrificing to their dress. In walking, running, rowing, skating, dancing, going up and down stairs, climbing trees and fences, the airy fabrics and flowing skirts were a continual impediment and vexation. Despite improvements in standards of health and falling child mortality rates, families were having fewer babies, and the resultant decline in the proportion of children from over half to about one third of the population made them more visible and their particular needs more easily recognized. Child Study became an important movement, spawning such proponents as Arnold Gesell of Yale, and later the beloved Dr.

Benjamin Spock. This focus on children as separate entities with special needs resonated in the area of their clothing. A time-tested truth is that children want to look like each other. To be dressed differently is to be conspicuous and open to ridicule. One of Sears virtues was that it provided a safe haven of middle-of-the-road style. Emily Post, a leading authority on etiquette, well aware of the importance of conformity in dress, advised: Children should be allowed to dress like their friends.

Next page

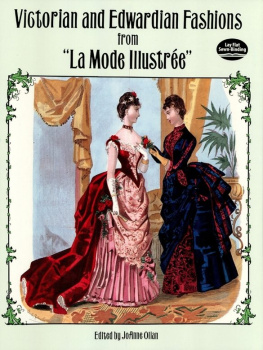

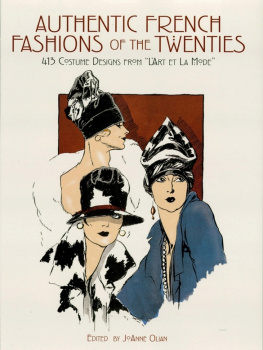

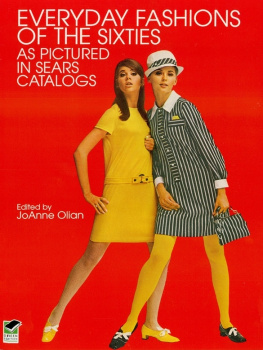

Edited by JOANNE OLIAN Curator Emeritus, Costume Collection Museum of the City of New York DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC Mineola, New York

Edited by JOANNE OLIAN Curator Emeritus, Costume Collection Museum of the City of New York DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC Mineola, New York At Dover Publications were committed to producing books in an earth-friendly manner and to helping our customers make greener choices Manufacturing books in the United States ensures compliance with strict environmental laws and eliminates the need for international freight shipping, a major contributor to global air pollution. And printing on recycled paper helps minimize our consumption of trees, water and fossil fuels. The text of this book was printed on paper made with 10% post-consumer waste and the cover was printed on paper made with 10% post-consumer waste. At Dover, we use Environmental Paper Networks Paper Calculator to measure the benefits of these choices, including: the number of trees saved, gallons of water conserved, as well as air emissions and solid waste eliminated. Courier Corporation, the manufacturer of this book, owns the Green Edition Trademark.

At Dover Publications were committed to producing books in an earth-friendly manner and to helping our customers make greener choices Manufacturing books in the United States ensures compliance with strict environmental laws and eliminates the need for international freight shipping, a major contributor to global air pollution. And printing on recycled paper helps minimize our consumption of trees, water and fossil fuels. The text of this book was printed on paper made with 10% post-consumer waste and the cover was printed on paper made with 10% post-consumer waste. At Dover, we use Environmental Paper Networks Paper Calculator to measure the benefits of these choices, including: the number of trees saved, gallons of water conserved, as well as air emissions and solid waste eliminated. Courier Corporation, the manufacturer of this book, owns the Green Edition Trademark.