Other books by Mark bitterman

Salted: A Manifesto on the Worlds Most Essential Mineral, with Recipes

Salt Block Cooking: Recipes for Grilling, Chilling, Searing, and Serving on Himalayan Salt Blocks

Bittermans Field Guide to Bitters & Amari: Bitters; Amari; Recipes for Cocktails, Food & Homemade Bitters

contents

Introduction

The Food That Time Forgot

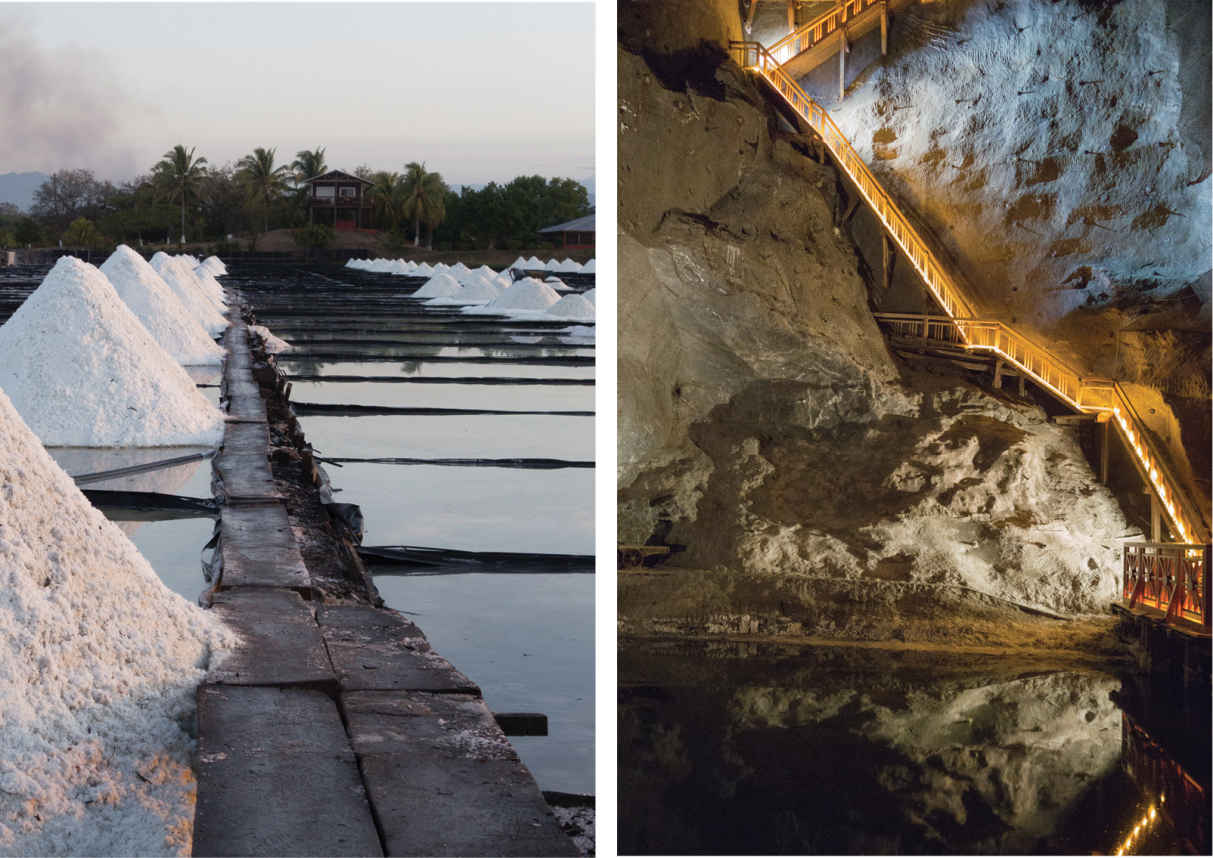

I awake early, an hour before the sun came up, eager to explore the salt farm. The air is warm on my skin, humid but fresh. Barefoot, I take the narrow path through the marsh grasses toward the salt ponds, through the cordgrass, flowering salicornia, and sea lavender. Salt crystals crunch under my feet as I pick my way along the rough wooden planks that cross the ponds. I stop in the middle, and the still waters around me mirror the golden fire of dawn reaching up through a purple sky, silhouetting the scattered volcanoes to the east and along the border of El Salvador to the south. Behind me, to the west, birds squawk like pterodactyls from the shadows of the mangrove forest, and the faint roar of the ocean fills up the space beyond. I kneel, sift my fingers through the brine, and touch the glistening crystals to my lips. The flavor is unlike anything on earth; this is craft salt.

Salt is a food that traces its roots back to the horizon where mankind meets nature. Over the millennia, across virtually every culture and locale, everyone who could make salt did make salt. It was never easy. Water had to be evaporated using the sun or fire from seas or salt springs, or raw salt rocks had to be broken and pulled by brute force from the earth. Environments like salt marshes had to be protected, and resources like wood had to be conserved. It took great ingenuity and skill, honed over centuries to a fine craft, to achieve salt making that was reliable and sustainable. Salt is one of the most varied, locally rooted, ingeniously produced, and distinctive foods on earth.

Our planet is home to many hundreds of craft salts, each a perfect, authentic reflection of its native ecology, economy, and culinary tradition. But in order to use them, you dont need access to every one. For practical use, there are only seven categories of salt, which all of the hundreds of varieties fall into: fleur de sel, sel gris, flake salt, traditional salt, shio, rock salt, and smoked/infused salt.

Each of the salts that make up these broad categories look and taste like no other salt on earth, from mild to bold, from briny to sweet, from dry to moist, from delicate to rugged, from tactfully unprepossessing to ostentatiously gregarious. A single respectful glance at craft salt reveals something truly amazing: Salt has personality. Each has stories to tell that give our purchasing dollars meaning and make our cooking fulfilling.

The mission of this book is to make you think differently about salt and empower you to make food that is better in every waytaste, texture, eye appeal, and nutrition. My aims are to share an appreciation for real, naturally made salt and to reveal how the lively personalities of distinctive craft salts will celebrate your food like nothing else. With a pluck of courage, we can unearth the lost truth of craft salt, reveal its ancient power, and explore new horizons of flavor and satisfaction in cooking.

Winning Salt

There are two ways to make salt. The most common salts are made by a process called winning, meaning evaporating salt water from the ocean, salt springs or wells, or from manmade brine. The other way is to dig it up out of the earth from a salt deposit.

Sea salts are the most common type of evaporative salt. Making them is simple enough, on paper: Collect some seawater in a shallow pond, keep it out of the rain, let the sun evaporate all the water, and then collect whats left. In reality its fantastically more complicated than that. The process has to be controlled to crystallize the minerals you do want and leave behind the ones you dont. You need a lot of space dedicated to concentrating the seawater, and then a tidy, manageable area for crystallizing the salt and collecting it. If it rains, youre done for, so you need to pick the right place, and then scale everything to perfection so that you can make a reasonable quantity of salt before losing everything. If a storm comes, you lose the whole harvest, or worse, the entire salt farm.

Modernization has thrown up its own challenges, including the threat to salt marshes of urban development and pollution of the oceans. Perhaps the most difficult challenge faced by traditional sea salt farmers is the advent of large-scale, mechanized salt farming. Challenges notwithstanding, skilled practitioners of traditional solar salt making can be found around the globe. From Guatemala mangrove forests to highland Bolivia salt flats; from the Philippines to Vietnam; across Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Slovenia; from India to Eritrea to Ghana and a dozen countries in between, solar salt making is a vital economic activity and a storied connection to the past. Salt springs also feed famed salt works from Spain to Peru to China.

Lacking either an arid climate or natural concentrated brines, people have to get inventive. Bringing seawater into greenhouses both heats the brine and surrounding air to accelerate evaporation and protects the slowly forming salt from rain. This method has taken off in recent years in the Americas, where an often inhospitable climate and an insistence on sustainability converge to push salt makers to innovate. Hawaii, Maine, South Carolina, Florida, West Virginia, British Columbia, and Newfoundland are homes to greenhouse or similar zero-emissions salt-making techniques.

Yet another way to make salt sustainably is to look in the opposite direction of the sun, which is to say, straight down. Salt makers from Iceland to Wyoming to China have harnessed natural geothermal energy to make salt. The Earths liquid mantle delivers more than twice the total of all humanitys energy output to Earths crust, superheating water that can be tapped at hot springs to heat pans filled with saltwater, creating exquisite salts in very inclement climates.

Fire-Evaporated Salt

What do you do if you want to make salt, but there is simply not enough sun, too much rain, or no other natural sources of heat? The simple answer would be to boil off seawater using wood or coal or oil. This method was once widespread. Entire forests in Europe were decimated. Entire regions of England were blighted by coal soot. Thirty pounds of raw seawater must be evaporated to make a single pound of salt. The next time you reach for a box of fire-evaporated salt, consider that fossil fuels are a big part of the price tag!

Today environmental concerns make relying exclusively on fossil fuels to do the job unappealing and impractical in most instances, but there are exceptions. Many of the best fire-evaporated salts start with naturally concentrated brines, such as from a salt spring, well, or marsh, or use the limited available sun and wind to pre-evaporate the seawater to concentrate it before boiling off the remainder to crystallize salt. After 100,000 years of exploitation by Neolithic and post-Neolithic people in France, Le Briquetage de la Seille was developed and run as a major industrial salt works, boiling salt spring brine in earthenware vessels, breaking open the vessels to remove the cake of salt, and then discarding the vessels in heaps, converting at least 200 acres of the once flat countryside into a land of sprawling hills. People in Chinas Sichuan province have for millennia been pumping concentrated brine from 2,000-foot-deep wells in the earth. Neolithic England was home to salt making in its southern salt marshesa practice that continues there today.