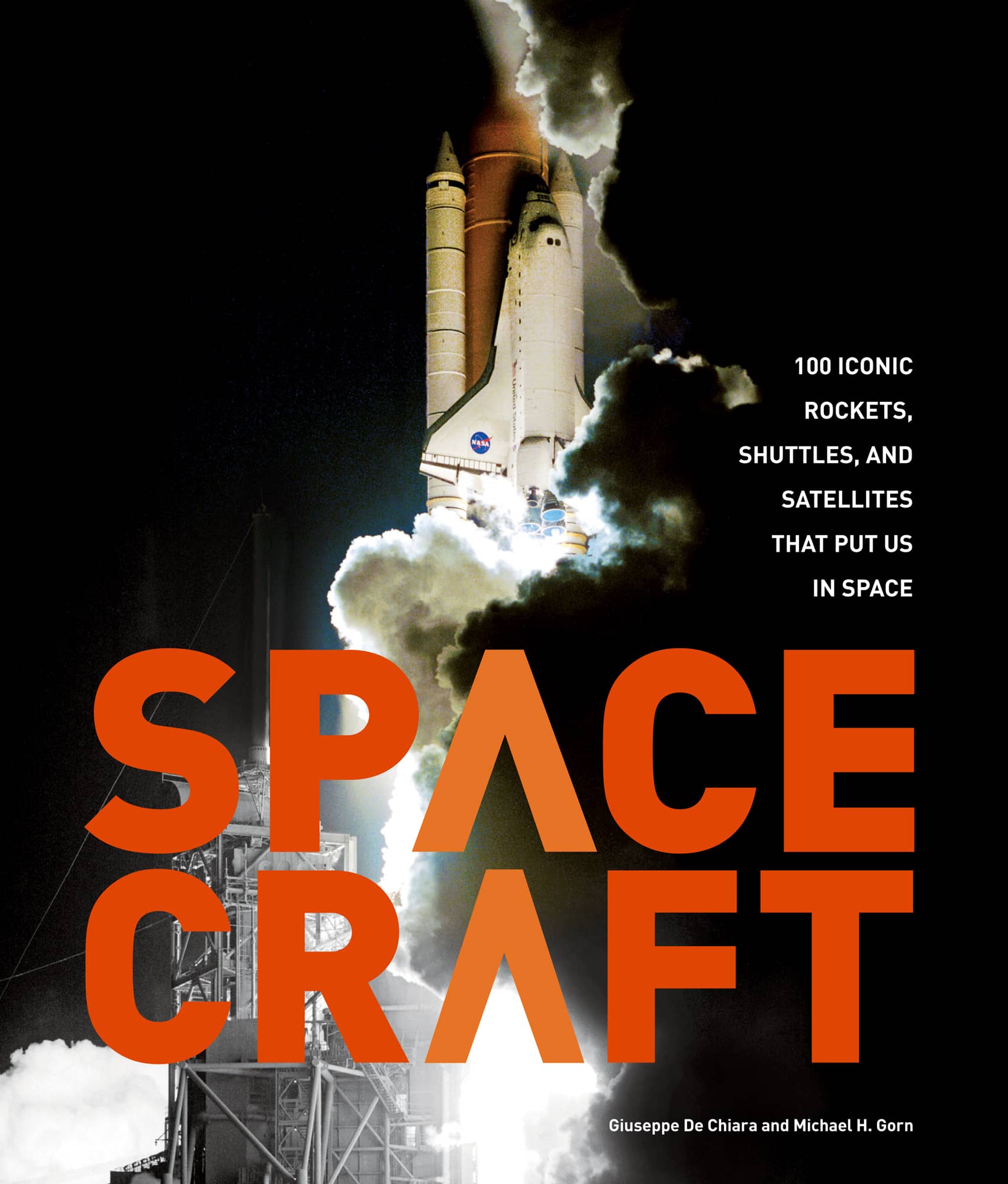

INTRODUCTION

Spacecraft tells the story of a momentous period in world history, when we escaped the atmosphere, looked down at the seas and the continents, and for the first time saw the planet in all its complexity, fragility, and beauty. At the same time, we looked skyward into the heavens and saw celestial phenomena as old as creation and as transcendent as the mind can fathom. The daring vehicles that accomplished these missions during the last six decadesfrom Sputnik 1 to the James Webb telescoperepresent the summation of space age exploration up to the early twenty-first century; they reflect the ongoing attempt by humanity to comprehend the workings of the universe and its parts.

The initial forays into space had Earth-bound parallels. At the dawn of the Space Age in the 1950s, President Dwight D. Eisenhower proposed legislation for a uniform network of high-speed freeways across the United States, ostensibly for national defense. Its usefulness, however, proved far wider. The National Interstate and Defense Highways Act of 1956 represented the biggest public works expenditure in US history (about $41 billion by the end of the Eisenhower administration alone) and expanded the American expressway grid by roughly 41,000 miles. More than that, it stimulated job creation and contributed to the economic boom of the 1950s, accelerated the pace of modern commerce, and narrowed sectional and regional differences, geopolitically unifying the country as never before. In their own way, the spacecraft that serve humanity return many of the same benefits.

Three years before the passage of this law, on the other side of the world, a New Zealander and a Nepalese Sherpa undertook a completely unrelated challenge. On May 29, 1953, Edmund P. Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became the first people to reach the summit of Mount Everest, the tallest point on Earth at 29,028 feet (8,848 meters). We didnt know if it was humanly possible to reach the top of Mount Everest, Hillary later said. Of no military, economic, or political consequence, reaching the peak of the world satisfied several deep-seated human drives: the pursuit of origins, the fulfillment of curiosity, the lure of adventure, the revelation of the unknown, and the test of endurance. These same motivations also typify the urge to explore space.

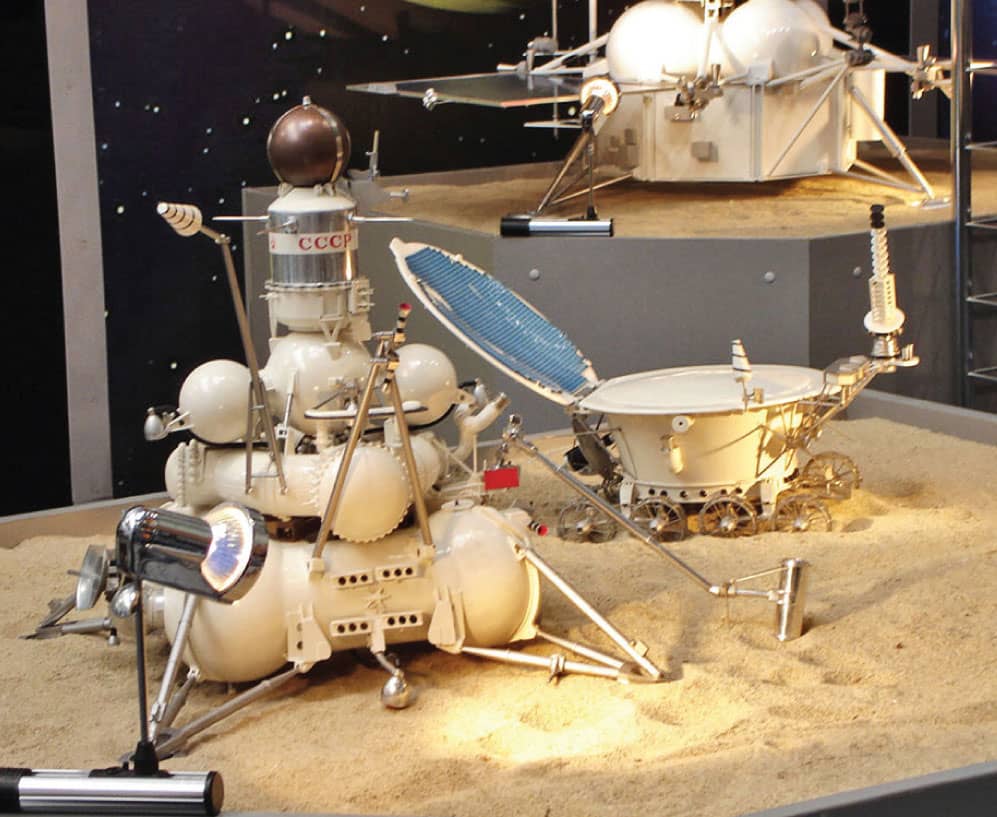

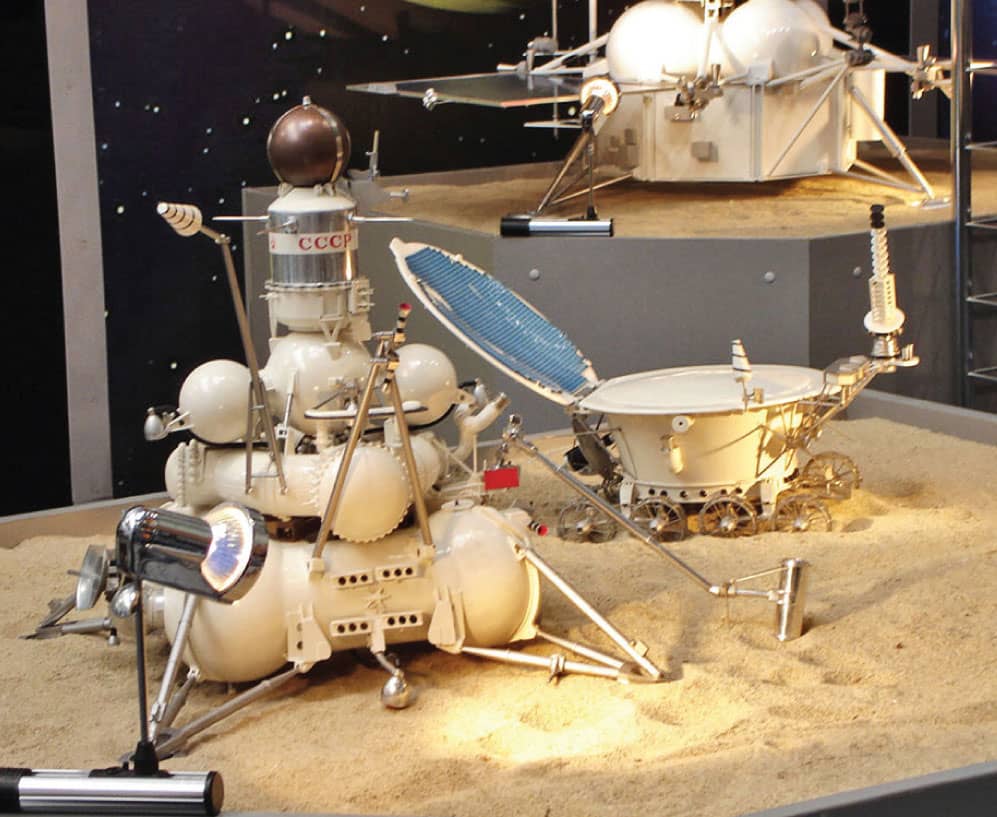

Because this book is confined to spacecraft designed for illumination rather than for tangible resultsfor endeavors like Mount Everest, rather than the National Highway Systemthere arises the inevitable debate between human and robotic sojourners. Will we engage with the universe through cosmonauts, astronauts, and taikonautsthrough sentient explorersor will automated orbiters and landers be our surrogates? The spacecraft profiled suggest that both have unique but complementary roles, that robots will continue to be sent to places too inhospitable or too distant for us, and that people will go where risk can be managed and where human intelligence cannot be substituted.

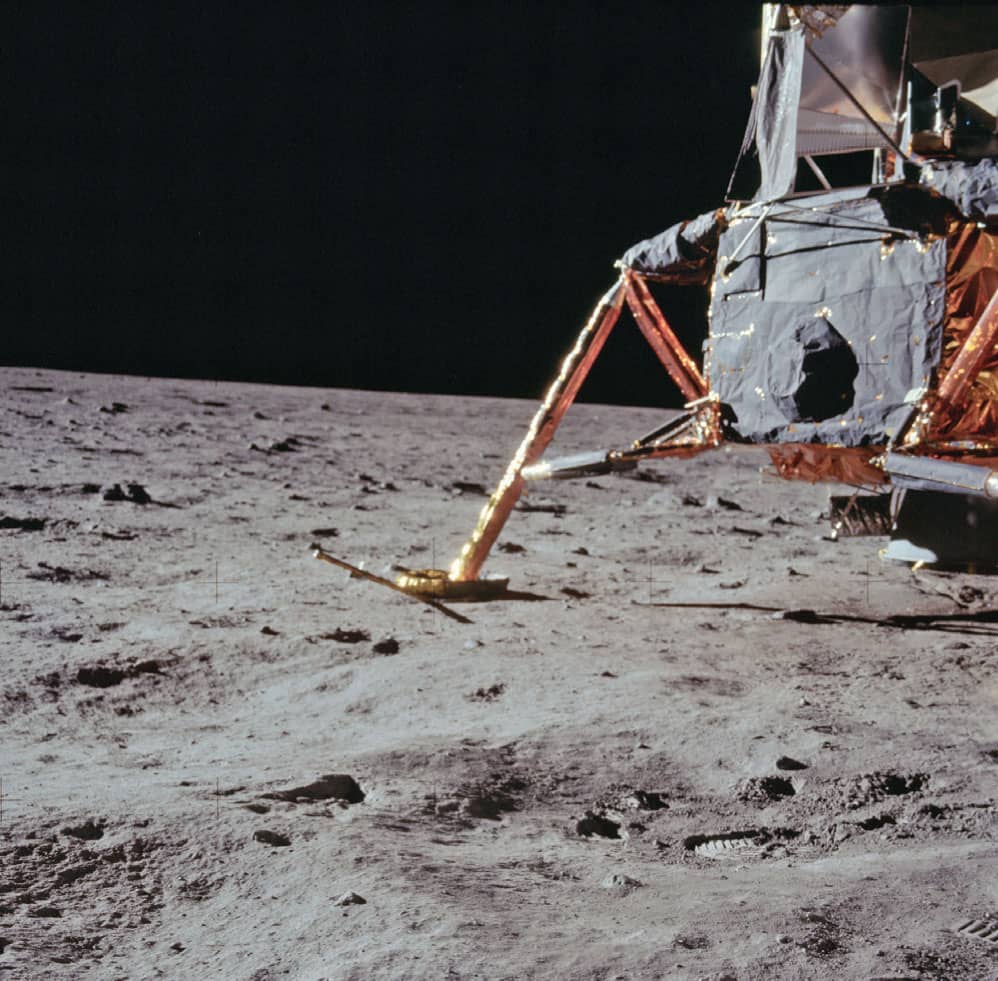

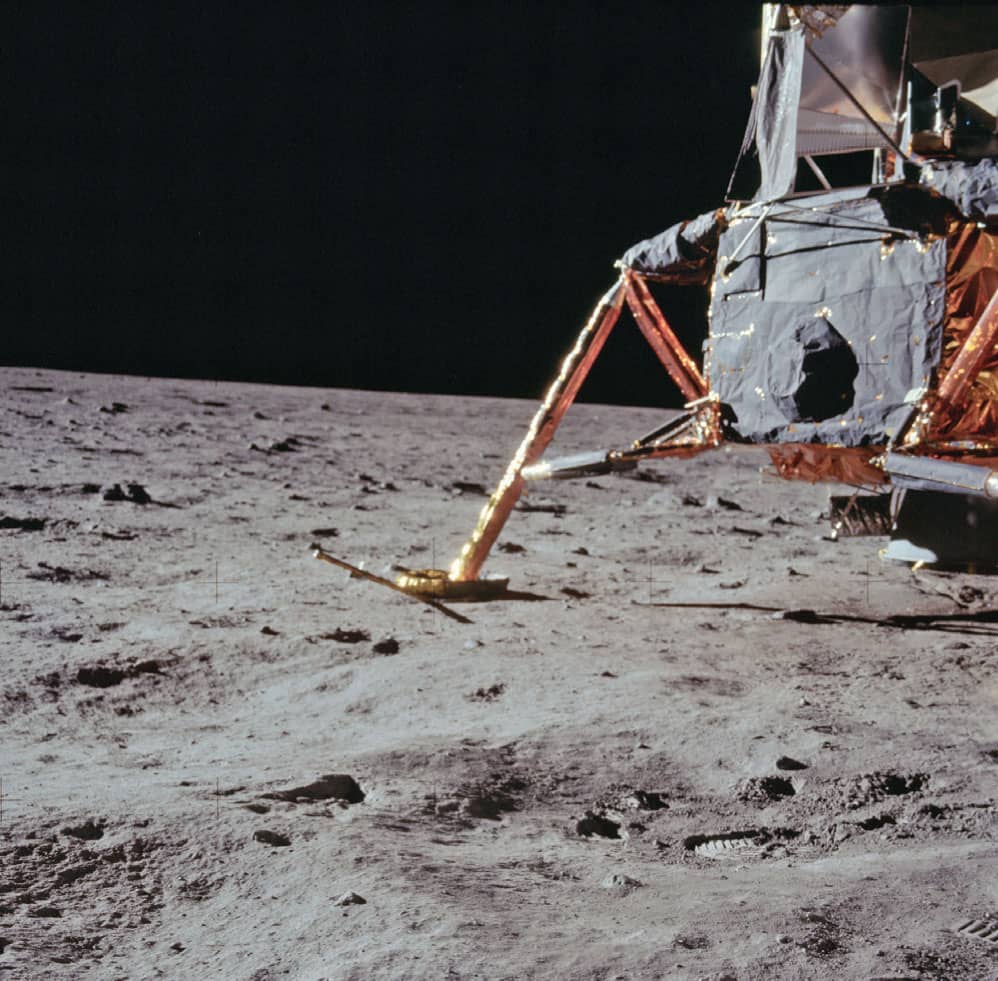

The Mars Science Laboratorys Curiosity rover performs many of the same chores as living spacefarers, without the limiting factors of time, fuel, supplies, and (to name only one safety issue) radiation exposurethe latter a serious health concern according to Curiositys own findings. On the other hand, the twelve Apollo astronauts who walked on the moon from 1969 to 1972 accomplished tasks impossible for machines. They witnessed and described the palpable texture of the moons surface, assessed the general features of its geology, and felt the peculiarities of lunar gravity in their every step and motion. They quarried large and highly varied quantities of rock and soil (842 pounds in all). They reported changes in their own physiology and psychology. They golfed! Then they returned to Earth with suggestions for future missions and explained how the experience affected them in artwork, memoirs, and the media.

Spacecraft also illustrates the international context of space travel over the last sixty years. It started as a duel between the United States and USSR, in the height of the Cold War, that not only involved a technological contest, but a struggle for world opinion. The Soviets and Americans trumpeted their space achievements to the world as proof of the superiority of their cultures, their governments, their economic systems, and their political ideologies. But once the Cold War ended, space exploration ceased to be a subplot in a global confrontation and in time assumed a radically different character.

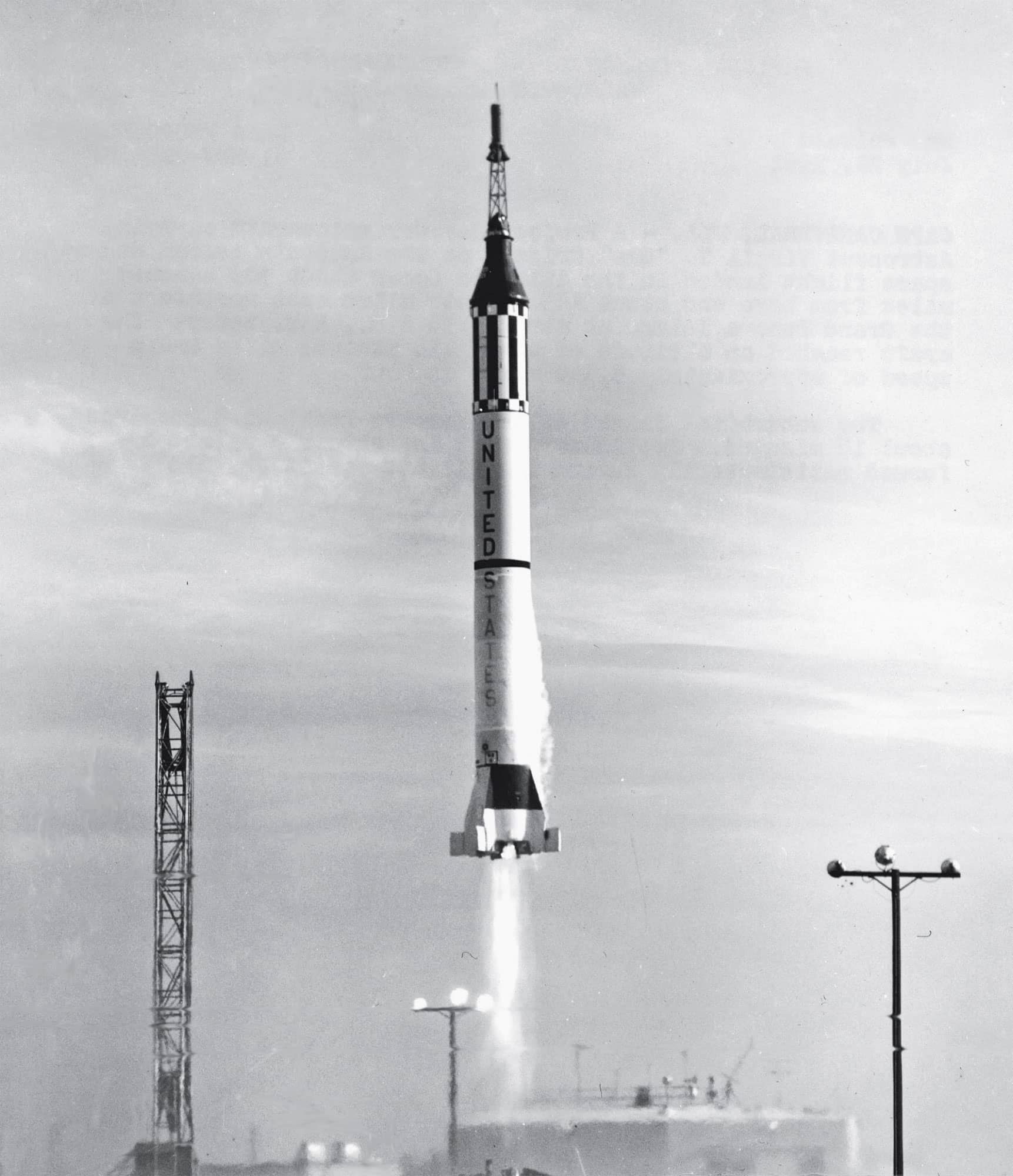

This evolution underlies the organization of this book. Divided into three parts of twenty years each, it traces three distinct periods. The initial one, from 1957 to 1977, covers the first Space Age, during which time the two superpowers vied for supremacy. The climax occurred with the race to the moon, a battle won by the United States in part because President John F. Kennedy imposed the daring objective of a lunar landing. That accomplishment erased the early lead held by the Soviets and enabled NASA to leap ahead to the finish line. But even though Apollo captured the big prize, the clash did not end there. To redeem themselves, the Soviets pivoted to new ground. By pursuing space station development with the seven Salyuts and Mir, the USSR restored its reputation and closed out the first phase of space exploration with an unquestioned mastery of long-duration habitation in orbit. The United States, meanwhile, scored its own late-innings win by concentrating on a series of spectacular robotic missions: the historic flights of Vikings 1 and 2 to Mars in the bicentennial year and the so-called Grand Tour of Voyagers 1 and 2 to the outer planets starting in 1977.

The next point on the timelinefrom 1977 to 1997was a transition period that left behind the Soviet-American polarity and opened a new era of tentative, multinational collaborations. This realignment began with the recognition by NASA and the Russian space agency that the end of the Cold War and the tightening of budgets left neither side with the resources necessary to build massive new projects in space. Consequently, to the shock of many, these former combatants agreed to forget (if not forgive) their old hostilities and to negotiate a partnership for an immensely ambitious undertaking: the International Space Station (ISS). Along with the ISS, the space shuttle also became a key contributor to the budding dtente in the heavens. Its large crew complement of up to seven enabled travelers of many nations, races, and creeds to work and live beside one another, and its cavernous cargo hold rendered it the sole means of transporting and assembling the outsized modules of the ISS. This era also marked the emergence of another transnational force: the European Space Agency (ESA), whose ten founding states came to epitomize fully integrated teamwork across borders.

Finally, during the third phaseentitled Space Exploration at a Crossroads, 1997 to 2017the study of the universe and its constituents became a global initiative. The docking of the ISSs first two modules in 1998 signified the realization of a massive multinational project with a lifespan expected to last at least until 2024, under the supervision of a five-member consortium consisting of the United States, Russia, Canada, Japan, and the ESA. At the same time, ESAs own program gained in stature, producing some of the worlds most sophisticated robotic spacecraft and launch vehicles. It also expanded its roster to include twenty-two member countries, embracing most of the European continent (ESAs governing council consists of Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom).