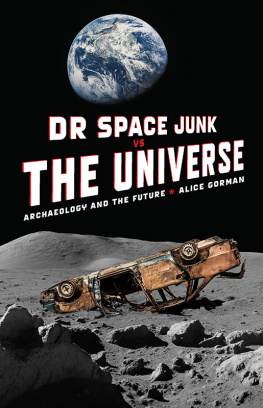

ALICE GORMAN is an internationally recognised leader in the field of space archaeology. She investigates the archaeology and heritage of space junk, planetary landing sites, rocket launches and antennas. She is a Senior Lecturer at Flinders University in Adelaide, and a Director on the Board of the Space Industry Association of Australia. In 2017 she won the Bragg UNSW Press Prize for Science Writing. Dr Gorman tweets as @drspacejunk and blogs at Space Age Archaeology.

This book is dedicated to the women of my family across four generations: my grandmother, Alice, my mother, Tish, my sister, Claire, and my niece, Stella.

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Alice Gorman 2019

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

ISBN 9781742236247 (paperback)

9781741244495 (ebook)

9781742248950 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

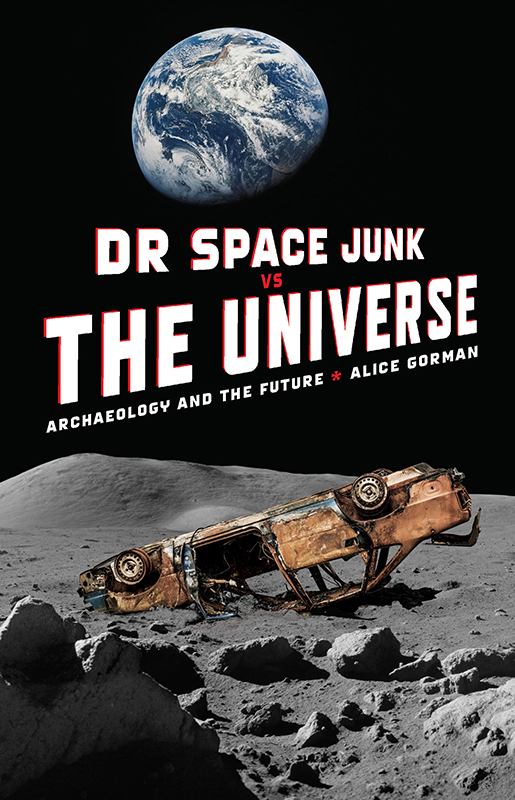

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Peter Long

Cover images NASA; loriklaszlo; and Depositphotos

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Theres something nicely counterintuitive about the concept of space archaeology. We generally think of archaeologists as people who dig down, trowelling through the topsoil and uncovering the deeper past beneath. Alice Gorman and her ilk dig, as it were, up into the heavens above the breath-able sky as well as into the dirt, to extract the debris that has fallen, Lucifer-like, from the heavens. History is the past, and archaeology is often assumed to be the deep past, but many people still think of spaceflight as science fiction and so therefore, to some degree, futuristic. And perhaps most strikingly of all we think of archaeology as slow: the pains-taking scraping away of layers, brushing dust from a half-cracked bowl. Space is, whatever else it is, fast we need to be moving at 40 000 kilometres an hour just to get there, and a body in orbit will be zooming along at somewhere between 24 000 and 32 000 kilometres an hour, depending on the kind of orbit were talking about.

In Alice Gormans wonderful book, the world is turned upside down. The past is above us rather than below. The immensely expensive and cutting-edge technologies of Apollo are junk. She takes us on a marvellous odyssey through the Space Age in terms of what it has left behind, rooting her expertise in her own life experience as well as in the grander narratives of the Cold War struggles and titanic engineering feats.

As Dr Gorman notes its wrong to think that the term history only applies to temporal remoteness. Heritage, she says, is about things from the past which are significant to people in the present, and which they want to keep into the future. This applies to very recent things like space exploration as much as it does to ancient rock art. History means everything thats been that has any kind of resonance to the present. It situates, speaks to and explains the nature of the present. There are many reasons why historical amnesia is an evil, but a main one is that such forgetfulness allows the unscrupulous to replace history with mythology. Myths make good stories, but because they are not true they are easily bent to malignant ideological purposes. There is an absolute need to keep the past alive in the present, both to avoid its mistakes and particularly where the glories of our human Space Age are concerned to remind us of what we were once capable. If ever it feels like contemporary humanity is stumbling, or perhaps shuffling backwards, it is salutary to remember that within living memory we as a species were capable of striding all the way to the Moon. It makes the hairs prickle on the back of my neck just to think about it. If I am certain of one thing about that troubled century, the twentieth, it is that in 10 000 years, when every other name has been forgotten, every politician and celebrity and artist consigned to the footnotes of specialist historical accounts, Neil Armstrongs name will still be common currency.

One thing space archaeology tells us is that the past is quicker, and more immediate, than we think it is. The Space Age sits at the moment in an uncanny valley of memory: too recent to be thought of as history in the Ancient Greek or Pharaonic Egypt sense of the word, but too far back in time to inspire the young generation. For a long time, going to the Moon was the stuff of the imagined futures of science fiction. Then, in 1969, all sci-fis dreams came suddenly true. And then again, blink or you might miss it, the dreams hurtled backwards, at 32 000 kilomtres an hour, into our collective past. Going to the Moon is no longer what we do; its what our ancestors used to do. An age science fiction predicted would last for thousands of years of human space exploration and colonisation was, in reality, compressed into a few years, packaged away and shut down. That historical moment, once blue-shifted by its approach down the speculative time-lines, is now red-shifted by its rapid retreat from us into posterity. It grows more distant every day.

Gorman neither over-romanticises nor dismisses the junk she champions. It cant all be conserved but most space junk is constantly moving, on a spiral that will bring it careering into Earths atmosphere at speeds that are, literally, meltingly fast. She sanely cites the Burra Charter, to do as much as is necessary and as little as possible to retain cultural significance. Every family farm has its machine graveyard and rubbish tip. Its OK to let them decay, to let the wind and the rain take them. Some space junk may pose dangers for future astronauts (as was so vividly portrayed in Alfonso Cuarns Oscar-winning 2013 movie Gravity); but we dont need to destroy everything currently classed as space junk either, over 95 per cent of all the stuff up there, to reduce the risks of collisions from orbital debris. We can do it in a smart way by thinking through all the heritage and environmental issues.

This book reminds us that outer space is not impossibly distant: that its almost close enough to touch, and that it often showers objects down upon us like the fragment of Skylab she keeps on her desk. As charming as it is expert, as gripping as it is surprising, Dr Space Junk vs The Universe deftly threads together the cosmic and the personal, the stupendousness of space with the lived experience of human beings down here, from Aboriginal Australians to 21st-century city dwellers, encompassing everything from astounding space technology to cake and cocktail recipes. Outer space may be an arena of velocity, but this is a book youll want to take your time with to savour, rather than to gulp. Its a book that juxtaposes the human and the universal, and thats important, because it helps keep vital the great human dream, in the longest terms of our future as a species, the greatest of all of them: that one day well retake that step to the Moon, only this time well keep on going.