T H E G R E A T E S T A D V E N T U R E

kosmos

A series exploring our expanding knowledge of the cosmos through science and technology and investigating historical, contemporary and future developments as well as providing guidance for all those interested in astronomy.

Series Editor: Peter Morris

Already published:

Asteroids Clifford J. Cunningham

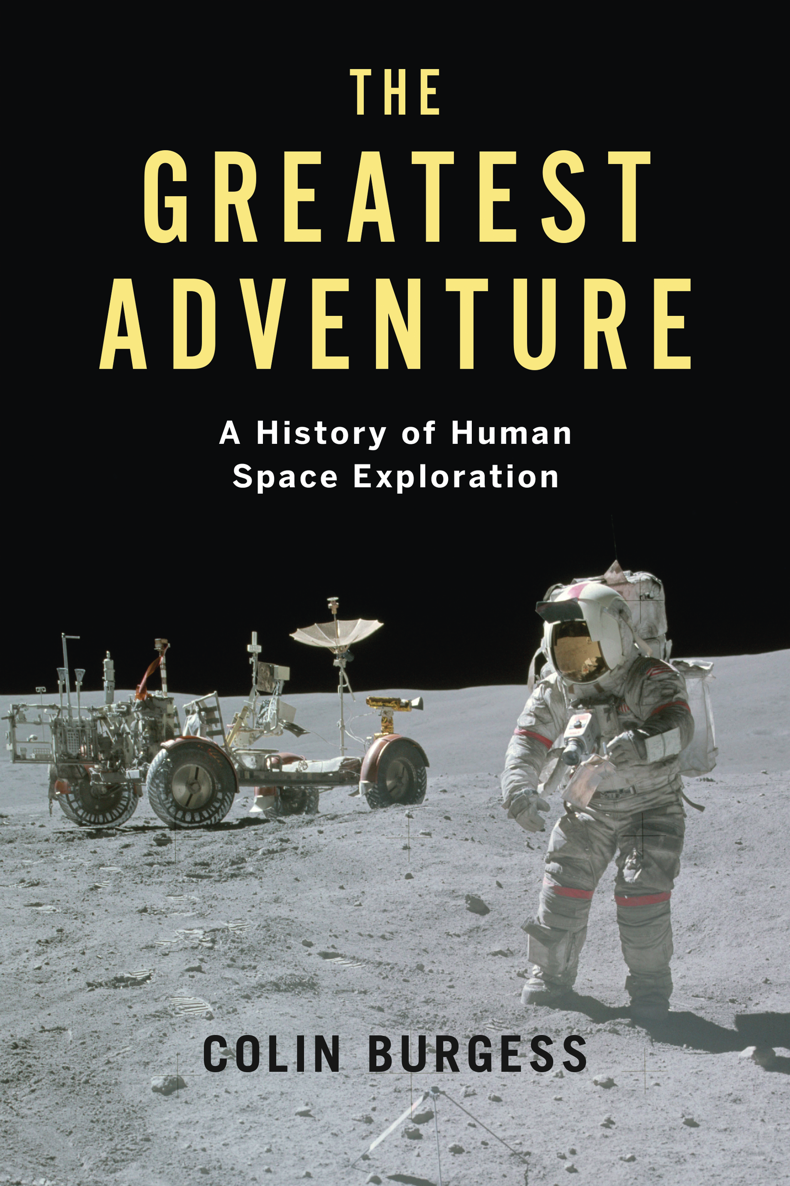

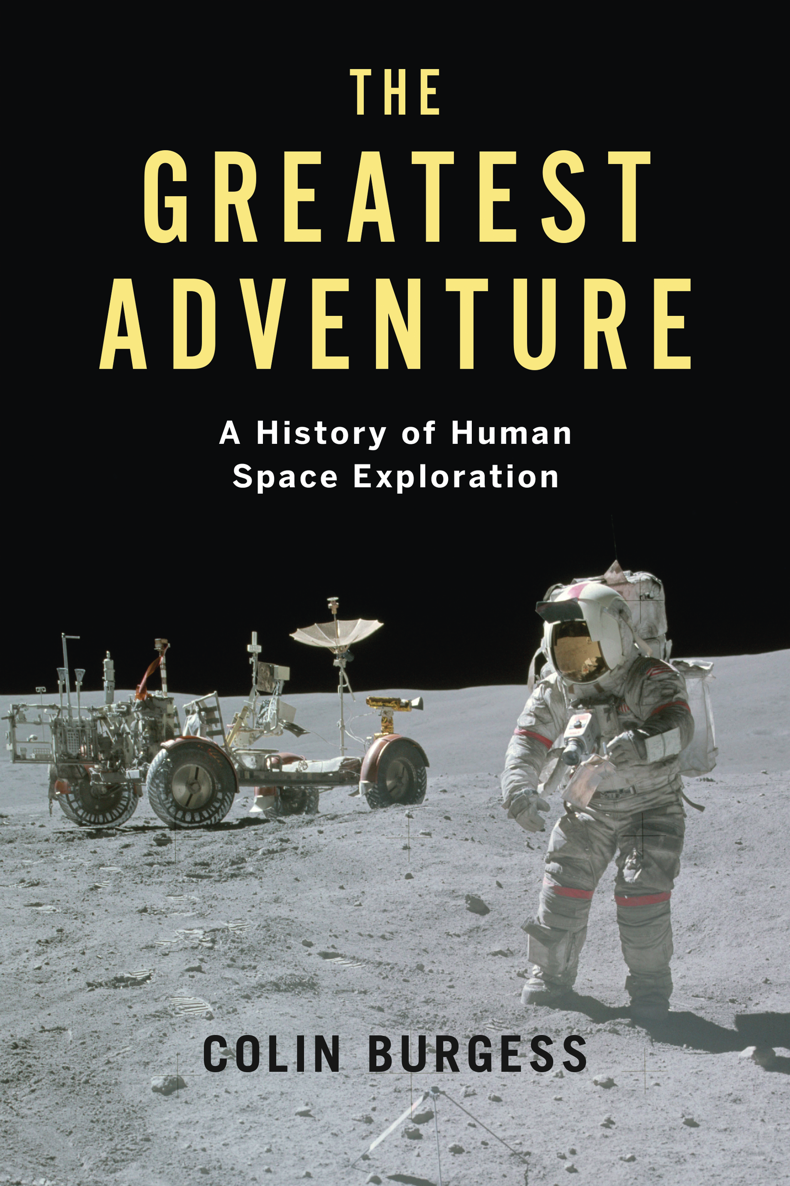

The Greatest Adventure Colin Burgess

Jupiter William Sheehan and Thomas Hockey

Mars Stephen James OMeara

Mercury William Sheehan

The Moon Bill Leatherbarrow

Saturn William Sheehan

The Sun Leon Golub and Jay M. Pasachoff

T H E

GREATEST

ADVENTURE

A History of

Human Space Exploration

COLIN BURGESS

Reaktion Books

To our Fallen Heroes: the crews of Apollo 1 (as-204), Soyuz-1, Soyuz-11, Chal enger and Columbia

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London n1 7ux, uk

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2021

Copyright Colin Burgess 2021

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78914 460 4

CONTENTS

Just as we continue to do today, our prehistoric ancestors would have gazed in profound wonderment at the rising silvery Moon. They could not fathom its purpose; all they knew was that its brilliant fullness gave a welcome light in the darkness and that it might exude some mystical, magical powers.

Few people understood that this and other venerated astronomical bodies they could see in the night sky might be solid, independent worlds; instead, they became a visible source of myths and fantasies, preserved and immortalized through successive generations and across many cultures. These myths have concerned such legendary Roman and Greek heroes as Selene, Diana, Astarte, Luna and Daedalus, as well as Soma, a Hindu god of the moon, and the Aztec sun and moon gods Nanahuatzin and Tecciztecatl.

Astronomy, the study of our Moon, the planets, stars and other celestial objects, is widely regarded as our earliest science. Once astronomers and philosophers began to comprehend our planets actual position in the universe, those myths of old mostly gave way to later theoreticians musing about ways to somehow fly to our closest celestial neighbour.

Speculation about the Moon intensified when Galileo used a crude refracting telescope to gaze not only upon our cratered Moon but beyond, to the moons of Jupiter. Later, circa 1609, fellow astronomer Johannes Kepler wrote a book called The Dream, a popular fantasy in which demons begin spiriting people away to the Moon.

In his classic 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon, French science fiction writer Jules Verne prophetically told of a lunar flight 7

T H E G R E A T E S T A D V E N T U R E

successfully carried out by three intrepid explorers. Incredibly, their fictional journey would bear many striking parallels with the first lunar landing by human beings more than a century later. The explosive propulsion device used to launch Vernes three-man aluminium spacecraft is called Columbiad, while the Apollo 11 spacecraft was named Columbia. Remarkably, the production and use of aluminium in manufacturing was relatively undeveloped at the time of Vernes book. The Columbiad craft is propelled on its journey to the Moon from Florida, not too far from the present-day Kennedy Space Center, and, just like Apollo 11 in 1969, it splashed down in the Pacific Ocean for recovery by naval vessels. There are many other startling similarities: one of Vernes lunar travellers has the surname Ardan, while Buzz Aldrin was a crew member on Apol o 11; furthermore, Neil Armstrongs middle name was Alden. Another adventurer is named Nicholls a near anagram of the surname of command module pilot Michael Collins. Verne also predicted the use of the spacecraft propulsion device known as a retro rocket, many decades before they were actually developed. Unlike Apollo 11, however, expedition leader Barbicanes crew carry along some non-human domestic passengers, as seen in contemporary woodcut il ustrations featuring a pair of cockerels and two small dogs, one of which has the intriguing name of Satellite. Verne may rightfully be regarded as a true doyen of science fiction, but even he could not have envisaged the rich and dramatic history that would unfold a century beyond the publication of his wonderfully prescient book.

Along with advancements in science and technology came the dis-couraging knowledge that we are firmly in the grip of gravity and that there is no simple method of breaking free from our planet. During the late nineteenth century there was a growing realization that only mighty rockets would be capable of defying the immutable laws of gravity, carrying vehicles beyond the atmosphere and into space. In a paper published in 1903, Russian science teacher Konstantin Tsiolkovsky fore-saw the development and construction of rockets fuelled by liquid propellants, including liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. This would later be the combination employed in launching the first successful rockets and, decades on, Americas fleet of space shuttles. An avid reader of science fiction, Tsiolkovsky calculated that Vernes description of using the massive Columbiad space cannon to propel his explorers to the Moon was flawed, as the massive acceleration forces created would 8

Prologue

crush any occupants to a bloody pulp inside their capsule. He relied instead on Newtons third law of motion: that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction the very basics of rocketry. Hailed as a true genius by the Soviets, Tsiolkovsky would come to be recognized as the father of astronautics.

There were others undertaking similar pursuits in rocketry around this time. Foremost among those in the United States was the physicist Robert H. Goddard, who began building and launching tiny rockets in 1914, much to the wary bemusement of people residing in Auburn, Massachusetts, who dismissed his quaint rockets as the work of a harmless eccentric. Undeterred, Goddard continued with his work and successfully launched the first liquid-fuelled rocket to an altitude of 56 m (184 ft) on 16 March 1926. Over the next fifteen years, Goddard and his helpers managed to launch no fewer than 34 rockets, eventually reaching a maximum altitude of 2.6 km (8,500 ft) and speeds close to 885 km/h (550 mph). Despite receiving very little financial or public support for his research work and test firings, Goddard would finally become known as one of the founding fathers of modern rocketry. In 1904, he told his high school graduating class, It is difficult to say what is impossible, for the dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow.

Other visionaries included physicist and engineer Hermann Oberth, who published his 92-page work Die Rakete zu den Planetenrumen (The Rocket into Interplanetary Space) in Germany in June 1923. Six years later, he expanded on this dissertation in a full-length book, Wege zur Raumschiffahrt (Ways to Space Flight). In the autumn of that year, 1929, he conducted a static firing of his first liquid-fuelled rocket motor, christened the

Next page