The year was 1961. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had only been in existence for three years, but already two spectacularly successful space missions completed by Soviet cosmonauts were having a dramatic effect on the civilian space agencys carefully planned, step-by-step human space flight program.

A Problem of Complacency

The single-orbit flight of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin in April 1961 hit America hard.

Unexpectedly divested of the historic prestige of placing the first person into space, NASA was accused of being too complacent. Every indication suggested that the Soviet Union was building up to this achievement, albeit with a program progressing under a strict shroud of secrecy.

This was in direct opposition to the open way in which NASA operated, with their events timetable openly announced. The Russians knew approximately when the first ballistic Mercury flight would take place, and even the names of the three prime astronaut candidates. With this and other technical knowledge available to their space chiefs, they were able to work to their own covert timetable and prepare to launch one of their cosmonaut team into orbit. They knew that the United States would only conduct a suborbital mission using a converted Redstone intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), which was far less powerful than their own R-7 booster.

As a former administrator of NASA, James Edwin Webb later admitted in hindsight, the Russians had made several data-gathering, unmanned flights in early 1961. We made a number of important, less spectacular, but very important flights. So both countries were coming down the line in flight programs that involved meteorological and other satellites.

We were flying monkeys and they had earlier flown dogs. Soon thereafter they were flying men. But by and large there were a number of quite important flights that showed increased horizons as to what could be done. Now, it was perfectly clear that they had been flying a booster that could lift 10,000 pounds into orbit, and the biggest thing we could put up was a Mercury, which is about 3,000 pounds. It was perfectly clear that we were behind them, and that they had been working at least four or five years before we got started on these bigger boosters.

President Kennedy shakes hands with NASA Administrator James E. Webb during a meeting in the Oval Office, 30 January 1961. (Photograph by Abbie Rowe in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston)

Boosting Old Reliable

In January 1959, just three months after NASA was established, the newly formed civilian space agency settled upon one of the most reliable large rockets ever produced in the United States, the Redstone, as the prime launch vehicle for its ambitious plans to place the first American astronauts yet to be selected into space. NASA also chose the McDonnell Aircraft Company to design and build the Mercury spacecraft.

A modified and enhanced version of Nazi Germanys deadly A-4/V-2 missile, the U.S. Armys Redstone was widely known as Old Reliable due to its renowned dependability and an impressive record of successfully completed launch and flight operations. Ahead of being selected by NASA, the Redstone had undergone several years of development and testing as a medium-range, tactical surface-to-surface missile for the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) at what was called the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama. This reliability was a clear factor in its selection by the space agency.

With the cooperation of the Army, NASA issued a request to the ABMA for eight Redstone missiles to be launched in the first phase of what was now called Project Mercury, to one day send a number of astronauts on proving ballistic or suborbital space missions. However, with a thrust of just 78,000 pounds, it was also recognized that the Redstone was incapable of inserting a manned spacecraft into Earth orbit. NASA was already looking beyond the ballistic program, and specifically at the Atlas series of rockets for their future manned orbital plans.

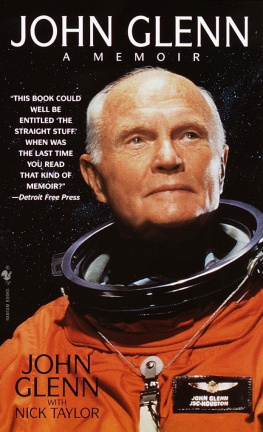

As history records, Navy Comdr. Alan Shepard was launched atop a Redstone rocket in his Mercury spacecraft Freedom 7 on 5 May 1961. Although he became the first American to fly into space, he was beaten to the honor of the worlds first spacefarer by cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, blasted into a single Earth orbit in his Vostok spacecraft just three weeks earlier. Still, NASA was persisting in its plans for an incremental space flight program, with future manned Redstone launches in its provisional manifest.

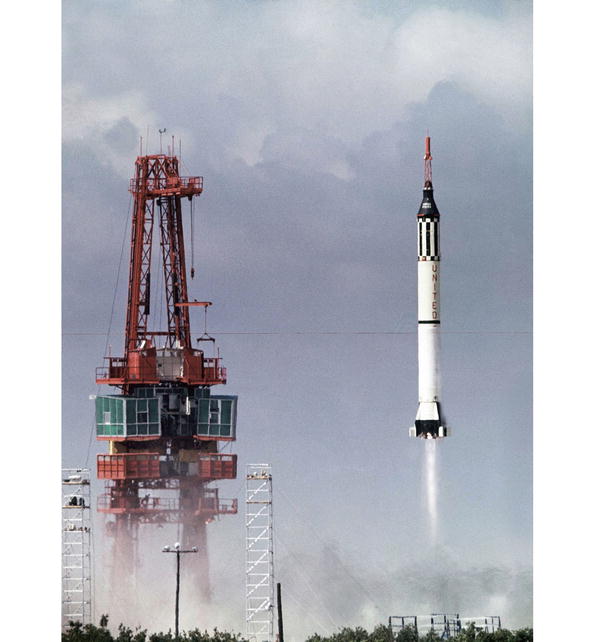

Alan Shepard is launched on Americas first manned space flight, 5 May 1961. (Photo: NASA)

With the fervor of an international space race rapidly gaining momentum, the United States and particularly President John F. Kennedy could no longer ignore events in the new frontier of space. On 21 May 1961, the President took up the political and patriotic challenge in a special message before Congress on urgent national needs, in which he asked for an additional $7 billion to $9 billion over the next five years to upgrade the American space program.

If we are to win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny, he declared, the dramatic achievements in space which occurred in recent weeks should have made clear to us all, as did the Sputnik in 1957, the impact of this adventure on the minds of men everywhere, who are attempting to make a determination of which road they should take . First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish. With that, he had daringly thrown down the gauntlet to the Soviet Union.

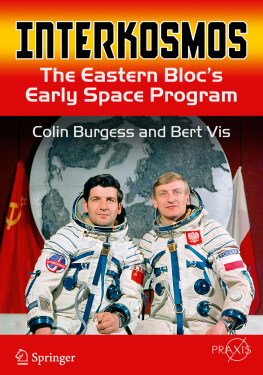

Soviet cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov. (Photo: Authors collection)

But there were more shocks to follow. On 6 August 1961, following a successful Mercury suborbital space flight by U.S. Air Force Capt. Virgil (Gus) Grissom a flight in many ways similar to that of Shepard NASA was once again left red-faced and self-questioning when the Soviet Union announced that cosmonaut Gherman Titov had been launched on an orbital space mission. His flight would last in excess of a day, and carry him through a total of 17 orbits of the planet. It was a massive propaganda coup for the Russians and their space efforts, and devastating news for NASA.

From left: John Glenn, Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom prior to Shepards Freedom 7 space flight. (Photo: NASA)