In a rousing speech that he gave at a Moscow rally on 22 October 1969 to welcome back the crews of the recent troika flight of Soyuz-6, Soyuz-7 and Soyuz-8, Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev observed: Our country has an extensive space program designed for many years ahead. We are following our own road, following it consistently and purposefully. Our road of space conquest is a road of solving fundamental tasks, basic problems of science and technology. The Soviet Union regards space explorations as the great task of learning and practically using the forces and laws of nature in the interests of men of labor, in the interests of peace on the Earth. These goals would be integral to a new and attention-grabbing facet of the propaganda-driven multi-national space effort that came to be known as Interkosmos.

A Bold International Venture

Interkosmos was the name given to a limited international program of peaceful cooperation in space research and technology originally dating from the mid-1960s, which was devised and orchestrated by the Soviet Union. Those behind the venture described it as a means of establishing mutually beneficial relations with Eastern Bloc countries through unmanned and manned space ventures. But it also served as a high-profile propaganda exercise, with the Soviet Union playing a particularly dominant role in the manned research program which carried guest cosmonaut-researchers into space, and controlling the release of most of the publicity associated with that program.

There was actually a practical engineering initiative behind the origins of the manned Interkosmos program. Spacecraft designers and engineers had long agreed that a Soyuz spacecraft should spend no more than 100 days in orbit. Beyond that time, the vehicles batteries and propellants would have gradually degraded, and this could have a potentially serious impact when crews attempted to bring the Soyuz back to Earth. This had obvious ramifications for the future Soviet space program, which involved sending cosmonauts on extended stays aboard orbiting Salyut space stations. As James Oberg pointed out in his book, Red Star in Orbit , they soon came up with a solution, but one that was extremely wasteful and fraught with unsatisfactory technical difficulties.

The solution was to send up a fresh Soyuz periodically to replace the aging one. On board the ship would be mail, fresh food and other cargoes; the men aboard Salyut could use their original Soyuz to send back down to Earth the results of their experiments, including exposed film, logbooks, tape cassettes, biological and medical samples, and materials produced in the furnaces.

Sometime in 1976 or so, planners must have realized that these Soyuz replacement flights need not be unmanned, flown entirely on autopilot Instead, two cosmonauts could visit the space crew, cheering them up.

Discussions were held as to the possible crewing on these Soyuz change-over missions, but sending two Soviet cosmonauts was seen as an unnecessary waste of resources. Instead, it was felt that some useful science could be carried out in the few days that this fresh crew would be present on the Salyut station. Thoughts then turned to sending up non-cosmonaut researchers. Obviously the commander would be a Soviet cosmonaut, and the person in the second seat need only be given minimal training to cope with any in-flight emergencies or incapacitation of the flight commander. Basically they would have to know how to control the Soyuz craft in any sort of emergency, and a better than basic knowledge of the Russian language was crucial. Discussion then began to center on what was occurring in the West. Around that time, the United States had come to an agreement with the European Space Agency (ESA), a consortium of nations including West Germany, Italy, France and Great Britain, which would allow ESA astronauts to fly aboard future space shuttle missions and participate in work programs, principally in the Spacelab module that ESA was to develop.

Although the first shuttle flight was still some years away, the Russians seized upon this initiative, which carried great potential propaganda value, and the Interkosmos program was born. It was formally announced in mid-1976, with the Eastern Bloc representatives being referred to as research-cosmonauts.

The Early Days of Interkosmos

The Interkosmos program actually had its origins as far back as 1520 November 1965, when designated representatives from the Soviet Union met with delegations from eight fraternal Communist countries to discuss the content, form, and objectives of a possible collaborative effort in space science and exploration. Those eight countries were the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Peoples Republic of Bulgaria, the Republic of Cuba, the Hungarian Peoples Republic, the Mongolian Peoples Republic, the Polish Peoples Republic, the Romanian Socialist Republic and the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. At the conference, the signatory participants exchanged views concerning the most suitable ways and means of pursuing cooperation in the exploration and peaceful use of outer space, taking into account the scientific and technical potentialities and economic resources of each particular socialist country. Questions on forming a program of joint research in the fields of space physics, space meteorology, organization of distant communications and telecasts, and space medicine and biology with the help of artificial satellites and geophysical and meteorological rockets were discussed. As well, the question of jointly constructing and launching satellites and the possibilities of specialists from interested countries cooperating in the development of new instruments and equipment for space exploration were discussed.

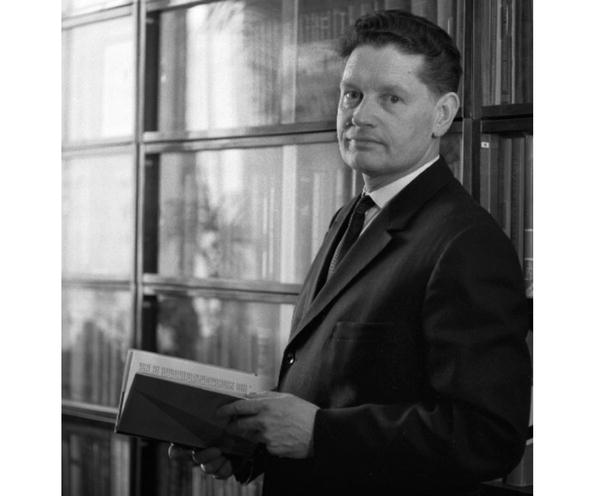

In Moscow six months later, on 30 May 1966, a Council for International Cooperation in the Peaceful Exploration of Outer Space was established under the auspices of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR the highest scientific institution in the Soviet Union which was at that time led by Academician Boris N. Petrov. The Council determined that the Soviet Union and the eight participating nations should each create a body to formulate a scientific program for this undertaking.

Academician Boris Nikolayevich Petrov, President of the Council for International Cooperation, USSR Academy of Sciences. (Photo: Authors collection)

At another conference the following year, held from 513 April, all nine nations signed an agreement to work together on a number of comprehensive space cooperation projects in five areas of study: physics, meteorology, biology and medicine, space communications, and the study of the Earths natural resources. The protection of the planets environment would be added to the list in 1976. Further agreements reached at the conference covered the holding of further conferences, symposia and meetings, as well as the exchange of visiting scientists.

Sixteen months later, on 13 August 1968, the signatories to the agreement submitted to the United Nations Secretary General a draft plan for an INTERSPUTNIK commercial system of international space communication that would meet the requirements of both developed and developing countries.