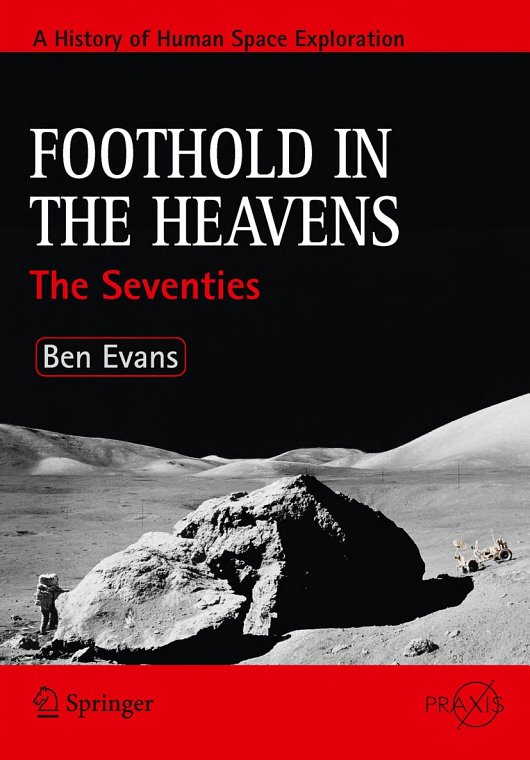

Foothold in the Heavens

The Seventies

Author's preface

When I set out to write a five-volume history of humanity's exploration of space, it seemed a big project, though fairly straightforward. Starting with Yuri Gagarin's pioneering voyage in April 1961, the journey through five dramatic decades promised to be an exciting one, with specific breakpoints between the volumes: the resumption of manned lunar landings in the Seventies, the arrival of the Shuttle in the Eighties, the development of the International Space Station in the Nineties and the increasing 'privatisation' of getting people into orbit and the first fee-paying 'tourists' in the Noughties. My intention was for something a little more detailed than a basic log of manned expeditions into space, but as time has rolled on, the project evolved into a far larger and more complex task than envisaged.

I must, therefore, ask the reader to forgive me for failing to strictly track an entire decade with each volume. The first volume, Escaping the Bonds of Earth, had to take into account some of the advancements of the Fifties as a prerequisite to focusing on 'its' decade, the Sixties. In this second volume, Foothold in the Heavens, I had to focus on particular episodes in considerable depth - the historic flight of Apollo 11 being a notable example - at the expense of covering an entire decade. Furthermore, I realised that spaceflight was not, and is not, a unique phenomenon, outside of public or political control. Rather, it has been an integral part of our social, economic and cultural fabric, and the lightning speed or snail's-pace slowness of its progress through the decades has been increasingly dictated by outside influences: the Bay of Pigs, the mythical 'missile gap' between the United States and the Soviet Union and the Cuban Crisis of 1962 were all instrumental in determining space policy. In the early Seventies, the progressive thawing of relations between the United States and the Soviet Union similarly impacted their respective space programmes. I feel it would be unconscionable to discuss our progress in space without paying tribute to why we were doing so, the obstacles we had to overcome in order to get there and the opinions, attitudes and feelings of the people whose dollars and roubles were paying for such endeavours.

By the last year of the Sixties, almost three dozen astronauts and cosmonauts had journeyed into space. They had circled the globe in their pressurised ships, they had ventured outside in bulky, life-sustaining suits and they had embarked on the first mission to the Moon. Culturally, socially and technologically, the world around them had changed in a thousand ways. Against the backdrop of a deepening crisis in Vietnam, floodlit by the problems of the United States at war with itself over issues of racial and social inequality and with an increasingly disaffected youth struggling to make its voice heard, the American programme lost much of the popular appeal that it had once enjoyed. In the Soviet Union, the increasing regression and repression of Leonid Brezhnev's regime led to widespread condemnation and mass emigrations from a country that considered itself the embodiment of the beauties of the communist state. Yet, ironically, it was actually the steady thaw of relations between these bitter foes which spelled the end of limitless budgets for human space exploration.

By the early Seventies, men had walked on the Moon and had occupied space stations in orbit around Earth and both the Soviets and the Americans could still take pride in their achievements. Astronauts, managers, scientists and even some politicians could see no reason why a manned expedition to Mars and a permanently-occupied lunar base should not be achieved before the end of the century. It might not be on the scale of Arthur C. Clarke's imaginings, but it was certainly more than a mere dream. However, for an increasingly apathetic public, the cost was excessive. The race to reach the lunar surface in the Sixties would be superseded by a considerably more frugal attack on the heavens in the Seventies. As Apollo wound down, America's efforts switched to developing a cheaper means of accessing space: the Space Shuttle, which would bring both tragedy and triumph and effectively confine the nation to low-Earth orbit for the next several decades. Similarly, the Soviet leadership lost interest: its practice of signing blank cheques for Chief Designers to score major propaganda victories against the capitalist West declined markedly. Its ambitious effort to put men on the Moon fell apart and it, too, adopted a more conservative, gradual system of mastering the new frontier of space.

My intention in writing this second volume has been to briefly explore some of the reasons why the political, social, cultural and economic climate changed so significantly for both superpowers in the final years of the Sixties and those first few pivotal years of the Seventies and how this impacted our aspirations in space. For as Westerners grew their hair and sideburns steadily longer, so the budgets for space exploration steadily shortened and steadily thinned.

Four decades later, we continue to live with the consequences of those frugal times, for our species remains chained in low-Earth orbit. Today, we are further away from having our representatives return to the Moon than John Kennedy was when he made his famous speech in May 1961. The establishment of Earth-circling space stations, although ever larger, more advanced, more sophisticated and more 'international', has done little to escape what Konstantin Tsiolkovski once called the cradle of humanity. In a sense, therefore, the early portion of the Seventies was juxtaposed by two ironic, opposing themes, for as the last Apollo crew left the Moon our species reached the zenith of its accomplishments - and abruptly stopped. Four decades later, though we have had, and continue to have, a secure foothold in the heavens, we are still waiting for the next team of intrepid explorers to carry us deeper into the Universe around us.

Ben Evans,

Atherstone, February 2010

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been possible without the support of a number of individuals to whom I am enormously indebted. I must firstly thank my wife, Michelle, for her constant love, support and encouragement throughout the time it has taken to plan, research and write this manuscript. As always, she has been uncomplaining during the weekends and holidays when I sat up late typing on the laptop or poring through piles of books, old newspaper cuttings, magazines, interview transcripts, press kits or websites. It is to her, with all my love, that I would like to dedicate this book. My thanks also go to Clive Horwood of Praxis for his enthusiastic support and to David Harland for reviewing the manuscript; I appreciate not only their advice, but also their patience in what has been an overdue project which proved more difficult to write than I had envisaged. I must once again thank Ed Hengeveld for supplying many of the illustrations. Others to whom I owe a debt of gratitude include Sandie Dearn, Ken, Alex and Jonathan Jackson and Malcolm and Helen Chawner. To those friends who have encouraged my fascination with all things 'space' over the years, many thanks: to Andy Salmon and Andy Rowlands, Dave Evetts and Mike Bryce and Rob and Jill Wood. Our two golden retrievers - the ever-hungry Rosie and the the attention-seeking Milly - have provided a ready source of light relief. Lastly, there are two others that I would like to mention as having played a great role in my life in the last year. Firstly, my friend Roy Lane, who tragically lost his battle with cancer in March 2009, and secondly, our beautiful nephew, Callum Jay Hooper, born on St George's Day, 23 April 2009, whose never-ending smile and chuckling laugh are a joy to behold.