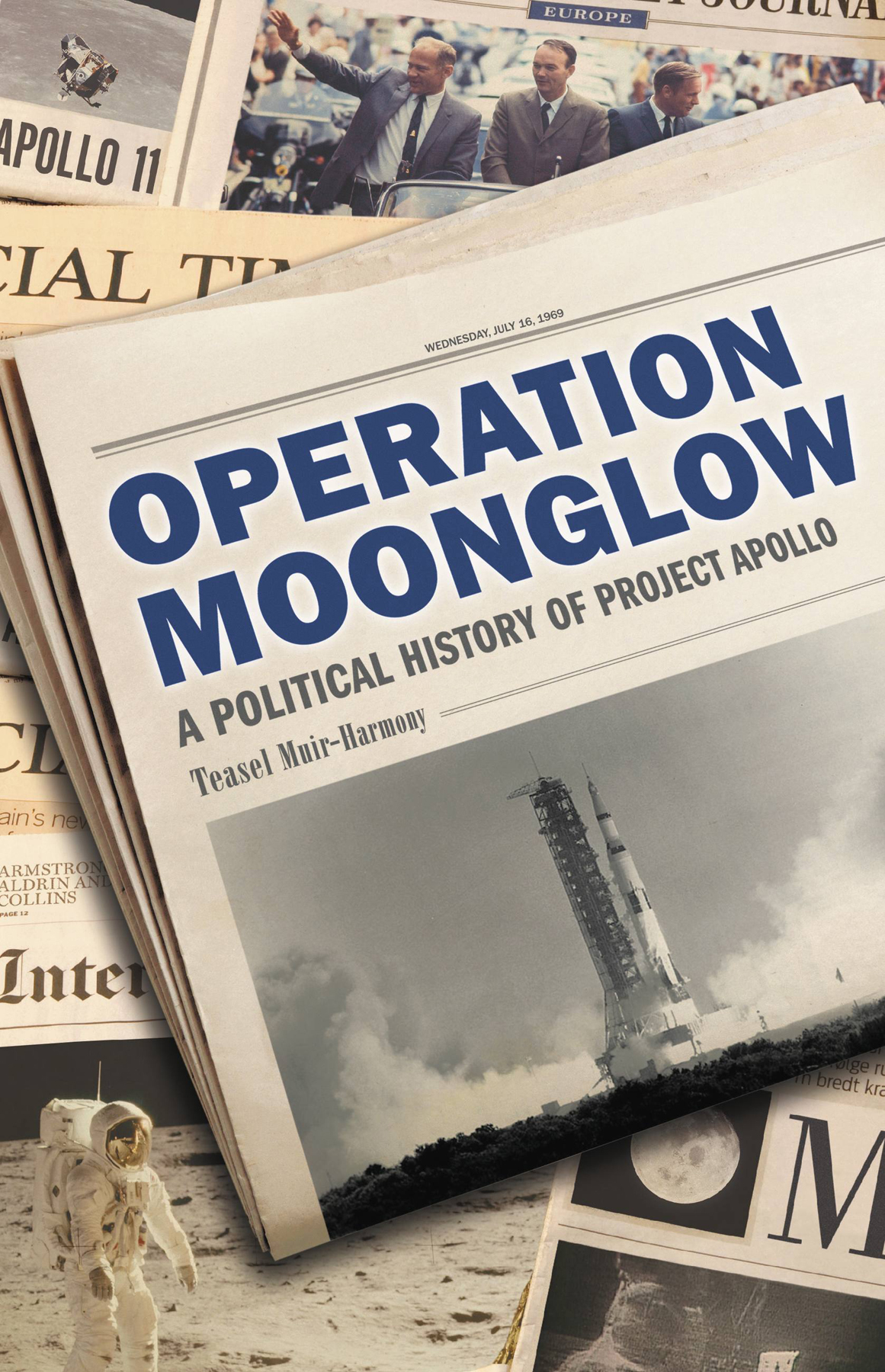

Copyright 2020 by Teasel Muir-Harmony

Cover images: NASA; Feng Yu / Shutterstock.com; oleschwander / Shutterstock.com; photo by Ken Hotchkin, Ken Hotchkin Collection, State Library of Western Australia 281436PD, sourced from the collections of the State Library of Western Australia and reproduced with the permission of the Library Board of Western Australia.

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: November 2020

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Muir-Harmony, Teasel E., author.

Title: Operation moonglow : a political history of project Apollo / Teasel Muir-Harmony.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020017479 | ISBN 9781541699878 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541699861 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Project Apollo (U.S.)History. | Space flight to the moonHistory. | Space. | Science. | Astronauts.

Classification: LCC TL789.8.U6A5 M86 2020 | DDC 629.45/4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017479

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-9987-8 (hardcover); 978-1-5416-9986-1 (ebook)

E3-20201016-JV-NF-ORI

For my parents, my first teachers.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

N ot since Adam has any human known such solitude as Mike Collins is experiencing, a NASA official commented when the Columbia spacecraft swung behind the moon on July 20, 1969.

Collins would spend the next forty-eight minutes orbiting the far side of the moon, blocked from all radio communication with his crewmates, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, who were on the other side of the lunar surface, as well as the rest of humanity back down on Earth. He felt this isolation powerfully.

This sense of solitude would not last long. What impressed Collins most on his return to Earth was not the isolation of space travel but its unifying effects. When I spoke with Collins almost fifty years after the flight, he told me, I thought that when we went to different countries that people would say you Americans achieved XYZ.what he experienced orbiting the far side of the moon: a profound sense of community.

Collins explained to me that everywhere the astronauts went, It was we. We human beingsWe did it, we did it. That was the punch line, everywhere we went. As the Apollo 11 crew circled the world on a postflight diplomatic tour, touching down in twenty-seven cities in twenty-four countries, they observed the same refrain: We did it.

That use of we instead of you Americans or you astronauts attests to the profound sense of collective participation felt by billions of people when humans first set foot on the moon. It also hints at the growing awareness of global interconnectionor the sense that we are part of one global villagethat arose alongside, and in part, because of the Space Age.

As Neil Armstrong climbed down the Eagles ladder and took one small step into the dusty lunar regolith, a record-breaking global audience waited with rapt attention. Never before had so many people come together to witness an event. But it wasnt just the numbers that made this audience exceptional. The sense of participation and global unity shared by billions of people around the world became one of the most significant consequences of the first lunar landing, with reverberations that affect us to this day.

During our conversation Collins added an essential point: this use of we around the world must have been worth its weight in gold for the US State Department and US Information Agency. As he knew well from his years as an astronaut followed by his tenure as the assistant secretary of state for public affairs, the unifying effects of Project Apollo were not just spiritual; they were also political.

This book arose from the right combination of intention and accident. Sitting in the US National Archives on an August afternoon in 2007, I was researching how scientific programs affect culture and politics. Taking the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatorys global network of satellite tracking stations as my jumping-off point, I spent the summer reading memos, reports, letters, and any other archival material I could get my hands on. In the archives airy reading room, I focused on the Smithsonians close relationship with the Tokyo Astronomical Observatory, a Meiji-era institution established in 1888.

The material I had been reviewing told me about the day-to-day workings of the cooperative international project at the observatory, but it seemed like something was missing. I had just read John Dowers Embracing Defeat, a masterful study of the postwar reconstruction of Japan from within. What matters, Dower stresses, is what the Japanese themselves made of their experience of defeat. How were the astronomers at the Tokyo Astronomical Observatory, as well as people throughout Japan, viewing US science and technology a decade after the war? And how was the US marshaling its scientific and technological programs in support of the nations political interests in Japan? With Dower fresh on my mind and some hours left in my day, I requested a few boxes from a collection that seemed promising.

What I found, tucked neatly in cream-colored folders, was a story that would come to dominate my life for over the next decade and transform how I understood the relationship between science, power, and globalization.

Holding up a US Information Agency field report dated September 4, 1962, I read, The Friendship 7 Exhibit in Tokyo was held at the Takashimaya Department Store July 26th through 29th from 10:00 a.m.6:00 p.m. daily, and was viewed by over half a million people, a crowd exceptional in size even by Tokyo standards.comprehend. This crowd was exceptional in size not just by Tokyo standards but by any other standards. Clearly, the department-store space capsule exhibit suggests a passionate enthusiasm for the US space program in Japan. But what is the larger significance of this popularity? I knew that John Glenn became a national hero within the United States after his flight. The country conferred the status of celebrity on him. But what did his space capsule mean to people in Japan? Why did they wait in a five-hour line to walk by his small, charred vehicle? Does this story hint at something larger, something more fundamental about the ties between early spaceflight and foreign relations?