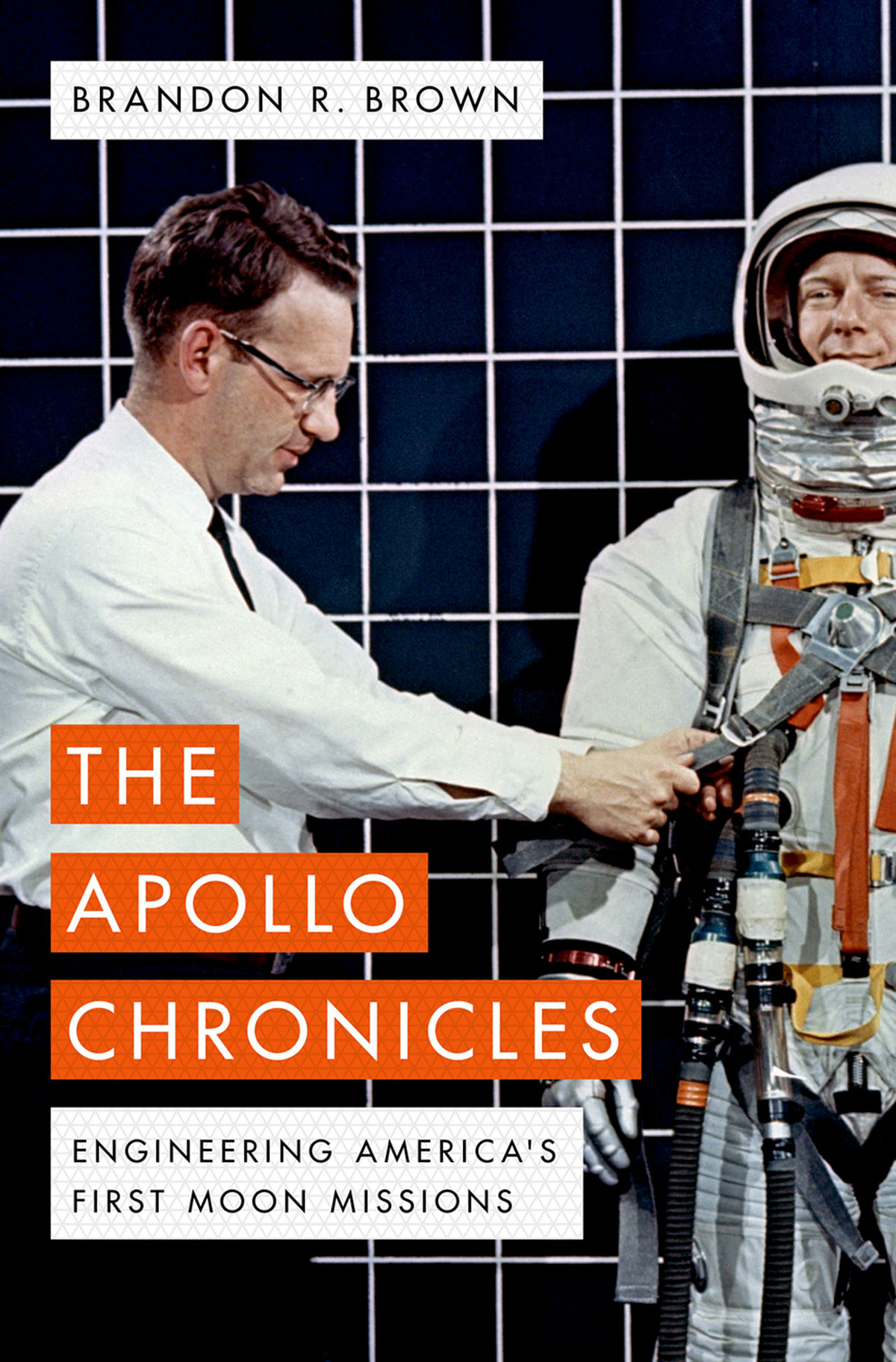

The Apollo Chronicles

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Brandon R. Brown 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190681340

eISBN 9780190681364

For my father and my mother.

For the Apollo engineers and their families.

Contents

On a winters night three years ago, I looked up at the full Moon, with its dark and light patches, and realized all at once that I knew very little about my fathers early career. Almost nothing. Id met many of his fellow engineers, heard stories of their quirks and their humor, but I had no idea what living and working the Moon missions was like in the 1960s. As of this writing, my father has just turned eighty-five. He has some very sharp memories of certain segments and certain projects, while other parts are understandably hazy now. After I started peppering him with questions, he brought out a box of keepsakes and memorabilia from his career days, talking through a review of each piece. He also shared a few phone numbers with me, of surviving colleagues. And when I showed him a list of names from NASAs archive of oral histories, he gamely circled those he knew would have interesting and important stories to tell.

I started reading everything I could find about ApolloAmericas program to land people on the Moon and return them alive to our planets welcoming surfaceand the steps that came before it. Many wonderful narratives focus on the astronauts and the blow-by-blow missions in space. But I mostly wanted to understand the projects earthly trenches, with engineers sweating details, deadlines, and decisions of a sort no person had faced before. In the eleven years spanning the formation of NASA in 1958 to the first Moon landing in 1969, the engineers cleared or circumvented every hurdle. If they did not solve every problem, they solved most and cleverly soothed the rest. Another set of books, fewer in number, detail the engineering work, including the piles of acronyms, the shifting, expanding organizational charts, the precise titles and versions of the various systems of each rocket, spacecraft, testing platform, and so on. The combination of NASAs strange internal parlance and Apollos monumental technical complexity raises a significant hurdle for many readers who might otherwise want to understand the work, the process, and the experience. What was it really like, day to day and month by hectic month?

The Apollo engineer Peter Armitage once told an interviewer, The real story is in the people and why they behaved the way they behaved. Nobodys ever written a book like that yetthe real people, the mistakes they made. With humility, I have tried to write a book that could leave the remaining engineers nodding in approval. But I also have written this book for anyone my age or younger. I was born in early 1969, months before the first Moon landing, and by the time my generation became aware of the world, Apollo was old news.

This book is not a memoir. As the least interesting element involved, your author will now recede. Neither is it my fathers story, though a few of his anecdotes will improve the pages that follow. And while I now appreciate just how brave our astronauts were, to sit on towers of explosive fuel and venture into a deadly realm, this book is more concerned with the astronauts protectors. In it, I focus on the Earth-bound: the welders of space-worthy seams, the designers of heat shields, the stitchers of spacesuits, and those who computed razor-thin trajectories through space, with disaster awaiting any deviation or missed step. As you read, youll sit with the mystified engineers who, barely out of college, watched warning lights blink on at the worst possible times. Youll hunker with the rocket engineers in the shaking walls of a block house during tests of the worlds most powerful rocket engines. Youll crawl with draftsmen over sprawling, improvised tables, drawing around the clock to complete hundreds of schematics. And youll sit with young, farm-raised Americans learning rocketry from imported German experts.

The stories, even the ones we havent yet lost, are nearly endless. Any attempt to comprehensively honor the four hundred thousand minds that pioneered the missions would be as impossible to assemble and write as it would then be to read. You will meet a number of the engineers but avoid long parades of names. This book will explore the Apollo years using a handful of main characters like blood cells moving through the various limbs of NASA. I want to urge the reader against the impression that these individuals were super-human. Two were most definitely visionaries, but Ive selected others because they were involved in key milestones, worked in multiple parts of NASA, and, crucially, have retained detailed memories of the Apollo era.

The first act of a dramatic arc to the Moon began in October of 1957. When the Soviet Union put a metallic artificial moon in orbit around the Earth, Americans quite nearly lost their minds. What did it mean that our enemies, at unprecedented speeds and heights, could methodically paint these bandsthese orbitsagain and again over our skies? Could the Sputnik see us? Was it a hostile device? Could it drop an atomic bomb? As the political historian Walter McDougall wrote, For the first time since [the War of 1812] the American homeland lay under direct foreign threat.... Newspapers compared flat-footed America to some fat Roman lolling in the baths before a barbarian invasion.

Never mind catching up, the nation thought. How could we get into space at all? What did the country have in its engineering cupboard? If nameless Soviet scientists were plotting even larger and more menacing missions, who would lead the way for the humiliated United States?

Before experiencing 1957, you will meet some of our cast in earlier times. In most cases, they had little inkling that history would sweep them up and push them onto a brightly lit technical stage. The world would soon watch them working in a theater of bewildering scale and scope. When the curtain rushed open, they would stand without script or rehearsal, looking to one another for whatever relevant experience they could muster. And to a surprising extent, humanitys peaceful path to the Moon relied on ideas born in war.

July 2018

I first want to thank the engineers and scientists I have interviewed. In sharing their recollections and expertise, the following people breathed great life info this project: Bob Austin, Hal Beck, Eugene Benton, Aldo Bordano, Robert Brown, Marlowe Cassetti, Nesbitt Cumings, Caleb Fassett, Gerry Griffin, Mack Henderson, Frank Hughes, John Kastanakis, Ed Kowalchuk, Arnolia McDowell, Elric McHenry, Jack Miller, Thomas Moser, Debra Needham, Lee Norbraten, Catherine Osgood, Thomas Parnell, Henry Pohl, Wesley Ratcliff, William Sneed, Ken Young, Renee Weber, Cynthia Wells, Don Woodruff, and Len Worlund.