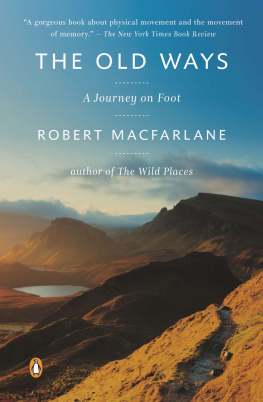

Robert Macfarlane

LANDMARKS

Contents

By the same author

Mountains of the Mind

The Wild Places

The Old Ways

Holloway

For Anne Campbell, Will Macfarlane

and Finlay MacLeod

landmark, seamark, or souls star?

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1886)

,

Where are your dictionaries of the wind, the grasses?

Norman MacCaig (1983)

1

The Word-Hoard

This is a book about the power of language strong style, single words to shape our sense of place. It is a field guide to literature I love, and it is a word-hoard of the astonishing lexis for landscape that exists in the comprision of islands, rivers, strands, fells, lochs, cities, towns, corries, hedgerows, fields and edgelands uneasily known as the British Isles. The ten following chapters explore writing so fierce in its focus that it can change the vision of its readers for good, in both senses. Their nine glossaries gather thousands of words from dozens of languages and dialects for specific aspects of landscape, nature and weather. The writers collected here come from Essex to the Cairngorms, Connemara to Northumbria and Suffolk to Surbiton. The words collected here come from Unst to the Lizard, from Pembrokeshire to Norfolk; from Norn and Old English, Anglo-Romani, Cornish, Welsh, Irish, Gaelic, the Orcadian, Shetlandic and Doric dialects of Scots, and numerous regional versions of English, through to the last vestiges of living Norman still spoken on the Channel Islands.

Landmarks has been years in the making. For as long as I can remember, I have been drawn to the work of writers who use words exactly and exactingly when describing landscape and natural life. of an arrow thudding into a tree. And for over a decade I have been collecting place-words as I have found them: gleaned singly from conversations, correspondences or books, and jotted down in journals or on slips of paper. Now and then I have hit buried treasure in the form of vernacular dictionaries or extraordinary people troves that have held gleaming handfuls of coinages. The word-lists of Landmarks have their origin in one such trove, turned up on the moors of the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis in 2007. There, as you will read in the next chapter, I was shown a Peat Glossary: a list of the hundreds of Gaelic terms for the moorland that stretches over much of Lewiss interior. The glossary had been compiled by Hebridean friends of mine through archival research and oral history. Some of the language it recorded was still spoken but much had fallen into disuse. The remarkable referential exactitude of that glossary, and the poetry of so many of its terms, set my head a-whirr with words.

Although I knew Gaelic to be richly responsive to the sites in which it was spoken, it was my guess that other tongues in these islands also possessed wealths of words for features of place words that together constituted a vast vanished, or vanishing, language for landscape. It seemed to me then that although we have our compendia of flora, fauna, birds, reptiles and insects, we lack a Terra Britannica, as it were: a gathering of terms for the land and its specificities terms used by fishermen, farmers, sailors, scientists, crofters, mountaineers, soldiers, shepherds, walkers and unrecorded ordinary others for whom specialized ways of indicating aspects of place have been vital to everyday practice and perception. It seemed, too, that it might be worthwhile assembling some of this fine-grained and fabulously diverse vocabulary, and releasing its poetry back into imaginative circulation.

The same year I first saw the Peat Glossary, a new edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary was published. A sharp-eyed reader noticed that there had been a culling of words concerning nature. Under pressure, Oxford University Press revealed a list of the entries it no longer felt to be relevant to a modern-day childhood. The deletions included acorn, adder, ash, beech, bluebell, buttercup, catkin, conker, cowslip, cygnet, dandelion, fern, hazel, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, mistletoe, nectar, newt, otter, pasture and willow. The words introduced to the new edition included attachment, block-graph, blog, broadband, bullet-point, celebrity, chatroom, committee, cut-and-paste, MP3 player and voice-mail.

When Vineeta Gupta, then head of childrens dictionaries at OUP, was asked why the decision had been taken to delete those nature words, she explained that the dictionary needed to reflect the consensus experience of modern-day childhood. at older versions of dictionaries, there were lots of examples of flowers for instance, said Gupta; that was because many children lived in semi-rural environments and saw the seasons. Nowadays, the environment has changed. There is a realism to her response but also an alarming acceptance of the idea that children might no longer see the seasons, or that the rural environment might be so unproblematically disposable.

The substitutions made in the dictionary the outdoor and the natural being displaced by the indoor and the virtual are a small but significant symptom of the simulated life we increasingly live. Children are now (and valuably) adept ecologists of the technoscape, with numerous terms for file types but few for different trees and creatures. For blackberry, read BlackBerry. A basic literacy of the natural world words which do not simply label an object or action but in some mysterious and beautiful way become part of it.

Landmarks is a celebration and defence of such language. Over the years, and especially over the past two years, thousands of place-terms have reached me. They have come by letter, email and telephone, scribbled on postcards or yellowed pre-war foolscap, transcribed from cassette recordings of Suffolk longshoremen made half a century ago, or taken from hand-drawn maps of hill country and coastline, and delved with delight from lexicons and archives around the country and the Web. I have had such pleasure meeting them, these words: migrant birds, arriving from distant places with story and metaphor caught in their feathers; or strangers coming into the home, stamping the snow from their feet, fresh from the blizzard and a long journey.

Many of these terms have mingled oddness and familiarity in the manner that Freud calls uncanny: peculiar in their particularity, but recognizable in that they name something conceivable, if not instantly locatable. Ammil is a Devon term meaning the sparkle of morning sunlight through hoar-frost, a beautifully exact word for a fugitive phenomenon I have several times seen but never before been able to name. Shetlandic has a word, afrug, for the reflex of a wave after it has struck the shore; another, pirr, meaning a light breath of wind, such as will make a cats paw on the water; and another, klett, for a low-lying earth-fast rock on the seashore. On Exmoor, zwer is the onomatopoeic term for the sound made by a covey of partridges taking flight. Smeuse is a Sussex dialect noun for the gap in the base of a hedge made by the regular passage of a small animal; now I know the word