has been a long time in the making.

This

Scots Dictionary of Nature has been a long time in the making.

As an artist, much of my work is about the Scottish Highlands, and in 2010, when I made an artists book called A Dictionary of Wood (which would be a first version of what you are reading now), I was doing research about the remnant Scots pinewood forests of Abernethy, and about Culbin, a Forestry Commission forest in Morayshire. Earlier that year, in a second-hand bookshop in Edinburgh, I had found an old Jamiesons A Dictionary Of The Scottish Language, abridged by John Johnstone and published in 1846. The original price of 11 was embossed in gold on the spine, and I bought it for 20. In opening random pages, Id come across words such as timmer breeks (timber trousers), meaning a coffin, and dedechack: the sound made by a woodworm in houses, so called from its clicking noise, and because vulgarly supposed to be a premonition of death. I loved these words and more: they had a resonance and a particular feeling to them that was sometimes poignant and affecting, and sometimes conveyed a prosaic descriptiveness that nonetheless spoke of close connections and an attentiveness to the nuances of the landscape, what it contains, how we move through it, and even specific times of day or year. Break-back: the harvest moon, so called by the harvest labourers because of the additional work it entails. There were also words like huam: the moan of an owl in the warm days of summer, evocative of that feeling of the haziness of a long, hot summers day as it spills into evening.

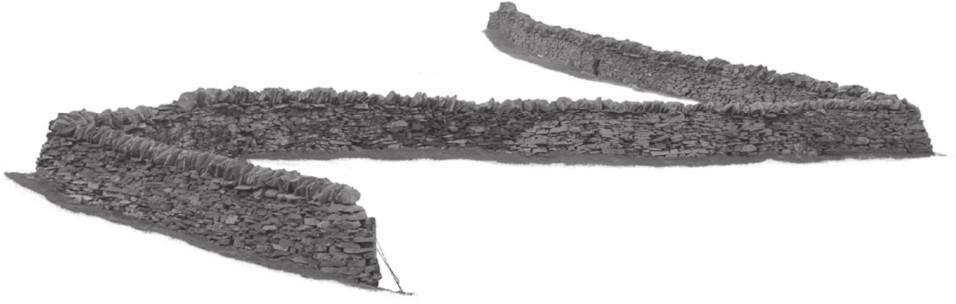

This old dictionary made me begin to wonder about lost connections to land and place and perhaps even ways of seeing and being in the world, and I began wondering what else I might find. Eard-fast means a stone or boulder fixed firmly in the earth, or simply, deep rooted in the earth, and its a word that seems to get to the heart of this book. It resonates with ideas of place and belonging, makes me think of deep connections to places and particular landscapes and makes me consider how language can assist or be at the root of such connections. Between 2009 and 2013 I was doing a doctorate and an element of my research related to the gradual changes that happen over time in the forests of Morayshire and Abernethy and how, when one is familiar with a place, one sees many more layers and begins to recognise the subtlest of these changes. I was also interested in how we make sense of and articulate our relationships to the land, both visually and verbally. As I walked with foresters and ecologists, I came across words like gralloch, used by a deerstalker to describe the innards of a dead deer (and the verb to gralloch, which so viscerally describes the task of removing them).

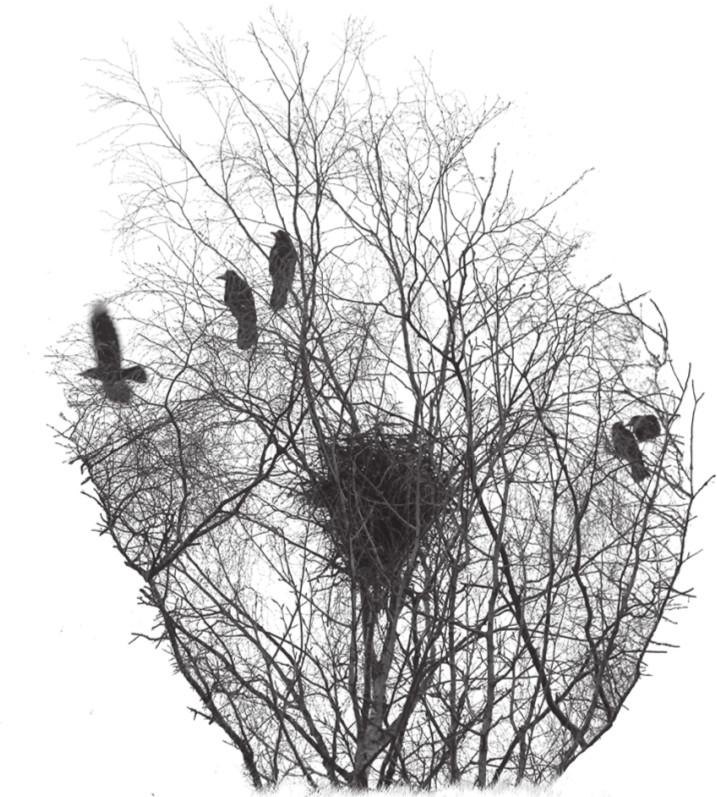

Such words were unfamiliar to me, and yet foresters and ecologists used them with ease and specificity to describe their everyday activities. As I listened and heard these new (to me) words, they informed additional ways of seeing and gave me different understandings of the places where I was walking and of the activities they were carrying out. And there were other phrases too, some quirky, others pithy. An older forester told me about a man who started working for the Forestry Commission but was not very good at his job: he was not wid material, the forester said. I decided to systematically go through the Jamieson dictionary looking for words related to wood, and did the same when I subsequently found a Supplement to Jamiesons Scottish Dictionary, edited by David Donaldson and published in 1887, and then a copy of The Scots Dialect Dictionary, edited by Alexander Warrack and published in 1911. I started making my way through each of these dictionaries, noting words most of them completely unfamiliar first in relation to wood, then over the years birds, weather, water, and of course, the land itself.

The focus on words relating to walking came at a later date, as I began to think about how we discover places by moving through them; and how places themselves (and what were doing in them) dictate how we move. At the same time, theres also more of a personal connection. H.M. Steven and A. Carlisle, in The Native Pinewoods of Scotland, wrote to stand in them is to feel the past, and in looking through these old Scots dictionaries theres a resonance with a different time as well as different connections to place, land, weather and, perhaps, a link to previous generations, both in the broadest sense, and in a more intimate and immediate sense. These are words we may remember our grandparents, or our great aunts and uncles, using.

My maternal grandmother came from a place that my family calls The Haggs, but on maps its just Haggs. Its a village just to the north of the Castlecary viaduct between Glasgow and Edinburgh, and to the east of the M80 motorway between Glasgow and Stirling. Fourteen family members lived in two small houses in a row of about five. The boys lived in one house, and my gran and her sisters lived with their parents in the other. The row is long demolished and must have sat somewhere above where the M80 now runs. They moved to a council house in Castleview Terrace in the 1940s, and my (great) Aunt Mary and two of her brothers lived there until they died, all of them well into their eighties.

Accent and language always seemed to spill from west to east as we went from the town nearer Glasgow, where I was raised, to The Haggs, which had a more easterly lilt and used different words and intonations. I wish I remembered more, or had recorded them. I learn from looking at these old Scots dictionaries that