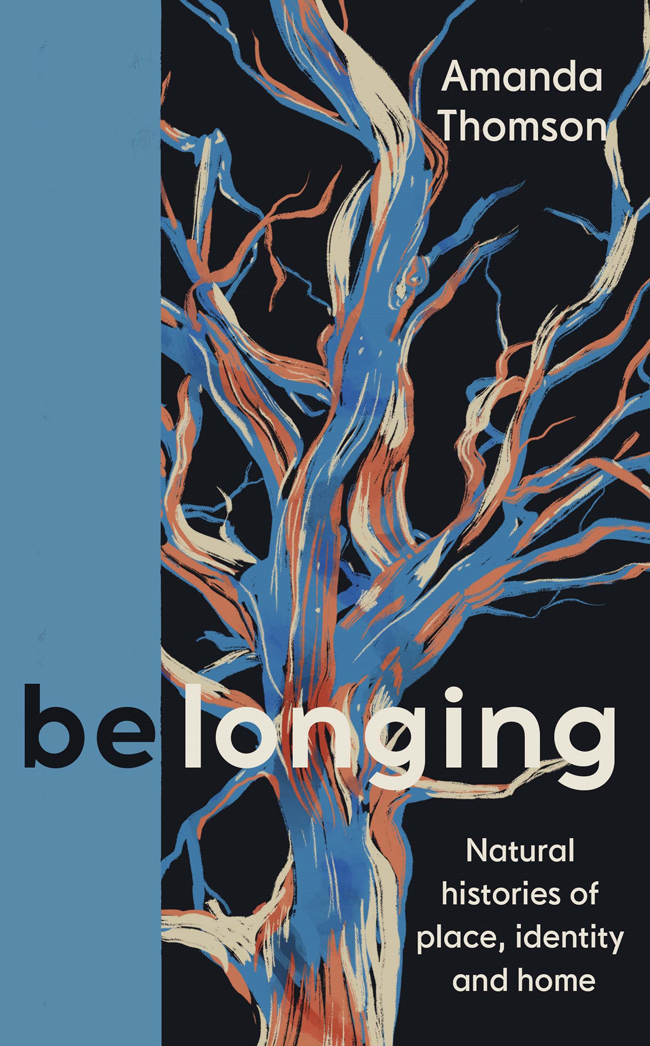

Amanda Thomson - Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home

Here you can read online Amanda Thomson - Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Canongate Books, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home

- Author:

- Publisher:Canongate Books

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Also by Amanda Thomson

A Scots Dictionary of Nature

First published in Great Britain in 2022

by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2022 by Canongate Books

Copyright Amanda Thomson, 2022

The right of Amanda Thomson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Extract from A Man is Assynt by Norman MacCaig, written c. 1967.

First published by Chatto & Windus in 1970 in A Man in My Position.

Published in The Poems of Norman MacCaig (Polygon, 2005).

Reproduced by permission of Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn.

For image credits please see

For more information about this book and

Amanda Thomson please visit: passingplace.com

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 83885 472 0

eISBN 978 1 83885 473 7

For Mum and for Elizabeth, with me every step of the way

Contents

understory | the (layer of) vegetation growing beneath the level of the tallest trees in a forest |

snag |

|

Prologue

OUT OF PLACE

I N THE BACK GREEN OF my mums house stand two rowan trees Ive known since childhood. At first, Id just be able to reach up and touch the lowest branch. Later, Id grasp it to swing myself up into the tree. It broke or was sawn off years ago now, and the trees themselves are old and feel frail, brittle. Any time theres a storm or high winds, my mum worries that branches will break off and knock out the telephone line or, worse, batter onto the roof.

The rowan is a folkloric tree in Scotland; theyve been used in medicine, to dye clothes, and are thought to ward off evil spirits and protect against disease. At our house in the Highlands weve planted two rowan trees, one on each side of the gate leading into the field. If they take, they will outlive us, and at one point, they might provide some protection from the wind. At the back of the house and up a hill is a small stand of four granny pines, which I always think of as our coven, standing watch over the house, which is made of larch. Abernethy Forest in Strathspey is a place Ive been making artwork about for some years, and its where Im now lucky to live. It has been described as an important remnant of ancient Caledonian pinewoods, and holds the most extensive area of these woods in Scotland. For many, its a stunning, heart-stopping place to be.

Theres a lovely phrase about the Caledonian pinewoods of Scotland that resonates with me every time I walk within them to stand in them is to feel the past. Its from a book written in the late 1950s, The Native Pinewoods of Scotland, by H.M. Steven, then Professor of Forestry at Aberdeen University, and A. Jock Carlisle. They write: The trees range in age up to 300 years in some instances, and there are thus not very many generations between their earliest predecessors about 9,000 years ago and those growing today. To talk about a general timelessness in these forests is somewhat clichd, but to consider how our very particular human time rubs up with such longevity is something else entirely.

At the back of my mums house, right at the border, a conifer looms taller than the house, casting its shadow over the green. One summer, jackdaws terrorised a blackbirds nest and the garden was in a constant state of agitation. The daughter of our upstairs neighbours planted that conifer when she was a child, after it had served its purpose as a Christmas tree in their house. Shes now in her seventies.

Early on in my walks through the Scots pinewoods of Abernethy, I began to notice the standing dead trees. They come in all shapes and sizes, barkless and pale amongst the deep greens of the living trees, pockmarked, riddled with the traces of beetles and beasties; some retain their bark, some are lichen-covered. Over time they will fracture their branches, sometimes shear half their trunks onto the forest floor. Such trees are known as snags, and when I investigated further, I found that deadwood in a Scots pine forest is incredibly important for the forests health. These trees can stand for decades, decaying quietly, slowly, leaching a gradual and steady release of nutrients back into the forests understory. They are home to a vast array of birds and insects, some very rare specialist saproxylic species, including several types of beetles, wasps and hoverflies and the lichens and fungi are dependent on these microhabitats ecological islands of otherness that dead and dying wood provides. Birds nest in their hollows and holes, and eat the insects that feed on the dead wood. I love the idea that the dead can sustain the living, and it has become an important touchstone for me how that which is no longer with us can make us who we are and can be a continuous source of strength or comfort.

We see different types of snags all over Scotland. Standing stones and other prehistoric relics dot the landscape and well sometimes come across the remains of Clearance villages and the shells of old crofts and sheilings. Closer to now lies evidence of more recent histories: paths that were once railway lines; factories and mills and churches now turned into housing and offices; an industrial crane that has been kept as a symbol of a citys ship-building past, that some will still remember in use. But we also have old letters, documents and photographs with, if we are lucky, names and dates and places written on the back. We have the National Records of Scotland and ancestry.co.uk. We drive past places that we used to visit, where people we know used to stay, or we return to places weve not been in a while, and something is evoked, or provoked, in us. Such things are testaments to earlier days and moments in our lives.

The snag is one of the understories of this book. Its also a great word. It can be something that catches our attention, emotionally resonates, arrests and holds us, often momentarily and sometimes surreptitiously. Although the word can have negative connotations, I think of snags as hooks on which we can hang past experiences that remind us of the disparate moments and aspects of our lives that have made us who we are, who we have become. In an old Scots language dictionary, a snag is a branch that has been completely broken from a tree, and I wonder about the continuity and disjuncture from our past that is a part of how our lives move on. I wonder how the dead, the things that are no longer with us, continue not just to influence but give succour to the present. Perhaps thats always been a concern of mine. The first artwork I made after discovering these Scots pine snags and their significance was called dead amongst the living. It started as a documentation of the dead trees that I encountered in a small area near the house I was staying in, and its become about the lives being lived around them still.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home»

Look at similar books to Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Belonging: Understories of Nature, Family and Home and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Amanda Mason [Amanda Mason] - The Wayward Girls](/uploads/posts/book/140005/thumbs/amanda-mason-amanda-mason-the-wayward-girls.jpg)