Ive always thought of myself as a student of culinary theory. I started collecting secondhand cookbooks and interpreting and analyzing the photographs contained therein from about the age of eleven, devising my own approaches (though sometimes only in my imagination) for preparing and presenting the dishes they depicted. Ive always felt that cooking is largely about creativity and inspiration, not just talented mimicry of other cooks recipes and favorite tricks of the trade. Whenever I managed any opportunity to cook for people in my youth, whether at sleepaway camp, at school, onboard a school ship, or at home for my family and neighbors, I inevitably added personal touches of my own to old standards, kept or eliminated elements according to my personal preferences, experimented by recombining ingredients and preparations in ways that excited me and that I thought would excite the taste buds of my dining audience (or victims, depending on the success or failure of my latest and greatest innovations).

Ive never been attracted to the esoteric in cooking for its own sake. The majority of my preferred methodologies are tried and true. My goal has always been to cajole the most flavor that can possibly be achieved out of my chosen ingredients. Ive studied classical French technique. I understand the importance of ambient temperature when creating a terrine, I know how emulsification works in a wide variety of circumstances, and I can fillet a fish and break down a chicken in no time flat. My souffls rise, my sauces dont break and, on a good day, I can smell a perfect sear or a tainted stock from fifty feet away.

I graduated with honors from the Culinary School of Hard Knocks. My early professional instruction came at the hands of hundreds, if not thousands, of hungry sailors in Her Majestys Royal Navy at every mealtime. They worked hard, played hard, and came to the table hungry, wanting to eat as much good food as they could get their hands on. They were tough. Yet Ive seldom, if ever, run across an audience more appreciative of the special touches that I learned to bring to some of the typical shipboard fare, whether it be a sprinkling of fresh herbs, a surprisingly tender and flavorful cut of meat, or a dessert that might have unexpectedly reminded them of home. They could be hard to handle when disappointed but purred like kittens when they were well fed. They taught me many valuable lessons, the most important of which is what it takes to get a good hot meal on the table in the real world.

Ive traveled extensively and have cooked and eaten a swath through miles and miles of ships messes, captains tables on cruise ships, VIP and state dinners in the capitals of the world; in hotels, both modest and fine, large and small; in taverns, restaurants, pubs, and bars of every stripe and description. As I cook and as I sample, I try to pay attention, both to the bad and the good on the plates in front of me.

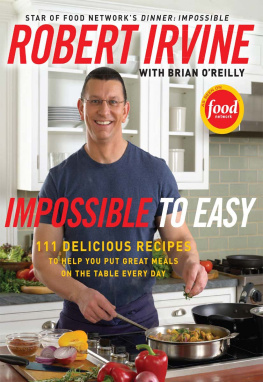

My experience as the crazed, overstressed, somewhat tyrannical (but lovable!) star of Dinner: Impossible has broadened my portfolio even more. Now I know that when youre cooking in an Ice Hotel and you cut into a potato when the temperature around you is eleven degrees Fahrenheit, its high moisture content causes ice crystals to form at the point of the cut, at which point its best to place it in water in a refrigerator to keep warm. I now have at least half a dozen recipes at my fingertips for venison appetizers, including venison Oscar, venison curry meatballs, venison hot dogs, and venison-stuffed shrimp, and they all serve four thousand. Ive learned that the proper application of liquid nitrogen to pureed mango will cause it to look and behave like Cheddar cheese. I know that fresh hogs ears and trotters need a bit longer than three hours when braised in an iron pot in a blazing hot fireplace before they are perfectly al dente. I can tell you with perfect confidence that frogs legs are delicious stewed with a little white wine on a cattle range over an open fire, that golf club shafts (with the heads neatly knocked off) make a terrific rotisserie turning device when grilling whole beef tenderloins, that Elvis ate fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches only once in a great while (gospel according to Priscilla), and that I will probably never completely and perfectly understand what children like to eat for their dinners.

I know these things because I am a chef. My job demands that I gather information, constantly experiment with cooking methods, preparations, and presentations, and endlessly obsess over the detail of every plate I serve. Its not for everybody.

But everybody has to eat, and most everybody either needs to, likes to, or wishes they could cook.

So, cook!

Its not hard to learn the mostly simple skills that can make you a good cook, even if you start without much knowledge at all. You can learn how to make a roux, and from there, how to make great soups, sauces, and stews. You can learn knife skills: how to julienne (cut meat or vegetables into thin strips), chiffonade (cut herbs and leafy vegetables into thin strips), or brunoise (cut vegetables into tiny bitsthe French have a different word for everything). Learn the difference between a simmer and a rolling boil, and you can perfect your approach both toward poaching an egg and cooking al dente pasta. Learn how to take whisk in hand and move it briskly in a clockwise motion (come on, how hard can it be?), and you too can make hollandaise and meringue. Then youre already more than halfway to eggs Benedict and lemon meringue pie. And if youre already handy in the kitchen, you know how satisfying it is to broaden your outlook and try new techniques, new flavor combinations, and new recipes.

Learn when to be patient and when to be active in the kitchen:

Patient: Wait an extra minute or two when putting a sear on a piece of fish or meat, especially a nice piece of meat. Most cooks, even practiced ones, try to move the food too soon and break the sear before the surface of the protein has perfectly caramelized. Waitforit.

Active: Whether youre working on stiffening peaks in a whipped cream or emulsifying that hollandaise, whisk with authority. Let that mixture know you mean business, and serve no meringue until it stands up and salutes you back.

In cooking, easy is a state of mind. It may seem easy for anybody to open a boxed, prefabricated mac-and-cheese product and mechanically follow the instructions. Theyll end up with something that resembles macaroni and cheese in a fairly short period of time. But youre not just anybody.

Youll start your macaroni water boiling, just as they will. But whilst it is heating, youll take a little flour and butter, whisk it in a saucepot for two minutes, pour in a cup of milk, and add shredded cheese to make a Mornay sauce, which they likely dont even know about. As it thickens and shimmers in the pot, youll cook your pasta, just like they will. In the time it takes them to add their manufactured powder to their macaroni, youll be combining your macaroni with your cheese sauce in a baking dish and popping it under the broiler. During the few minutes it takes to finish baking your homemade, soon-to-be-legendary family classic, its true that theyll already be gloomily ingesting their soulless, cheese productbased compound. But you, by persevering for perhaps five extra minutes, will instead be breaking into your cheesy, golden brown crust, inhaling the succulent aroma, and spooning and serving the warm, gooey perfection you created onto your plate and the plates of your family, their eyes glistening with gratitude and appreciation. Does that make you better than them? Youll have to decide. Im not a philosopher; Im a cook.