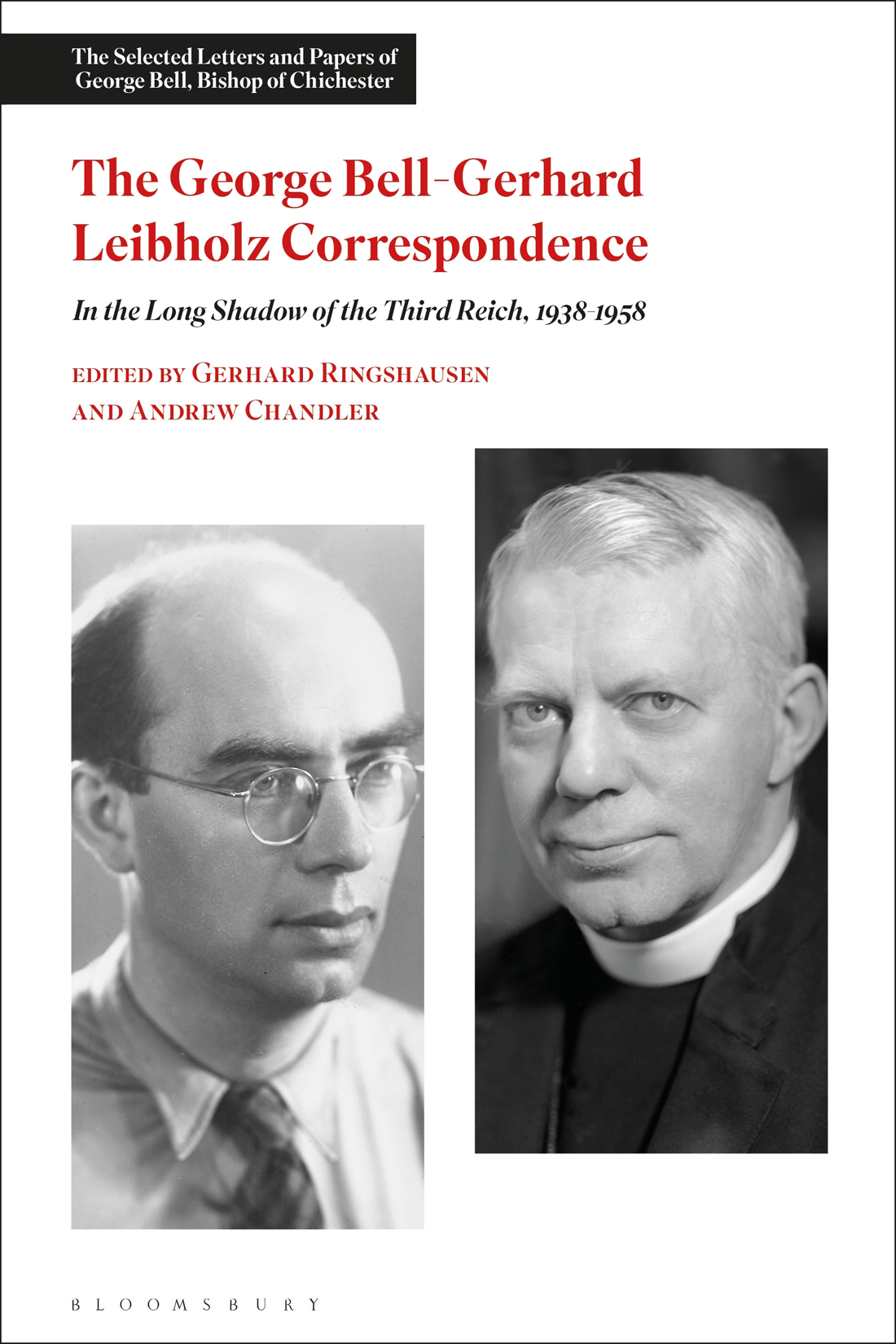

The George Bell-Gerhard Leibholz Correspondence

The Selected Letters and Papers of George Bell, Bishop of Chichester

GEORGE KENNEDY ALLEN BELL (18831958) was a figure of distinctive importance in many of the great political and religious landscapes by which we have come to recognize the history of the European twentieth century. He was a priest of the Church of England, a chaplain to an Archbishop of Canterbury, a Dean of Canterbury and then, for almost thirty years, Bishop of Chichester. Bell played a significant role in the development of that church, but his most distinctive contribution lay in the evolution of the international ecumenical movement. Bell became a leading light in the Life and Work movement and then the World Council of Churches, and a crucial bridge not only between the Church of England and other churches but between British Christianity and the churches of the world at large. In this context he came to know intimately such luminaries as Nathan Sderblom, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Willem Visser't Hooft and Eivind Berggrav.

In the context of the unfolding history of the Third Reich, Bell worked to support the persecuted, playing an important part in the German Church Struggle and also organizing relief to support refugee families who sought to escape abroad. He saved many lives. During the Second World War Bell repeatedly challenged British military and diplomatic policy, particularly over the obliteration bombing of German cities, and by his own secret initiatives he became a ready emissary of the German resistance against Hitler. Throughout his life Bell also sought to promote a new relationship between religion and the arts, commissioning work from the composer Gustav Holst and new drama from John Masefield, T.S. Eliot and Christopher Fry. He was, at the last, a figure of the twentieth-century world, a friend of Gandhi and Radhakrishnan, of the pastor Martin Niemller, the constitutional lawyer, Gerhard Leibholz and the artist Hans Feibusch.

The Selected Letters and Papers of George Bell, Bishop of Chichester seeks to represent the many, interrelating dimensions of the career of a man whom the German pastor Heinrich Grber considered as great a presence in his lifetime as Albert Schweitzer, Martin Buber and Martin Luther King.

Forthcoming:

The Speeches, Writings and Selected Sermons of George Bell, 19291958 ,

edited by Andrew Chandler

The George Bell-Alphons Koechlin Correspondence, 193354 ,

edited by Andrew Chandler and Gerhard Ringshausen

I am a learner from you, but I agree whole-heartedly with you.

George Bell to Gerhard Leibholz, 11 December 1942

I really think you are the living Christian conscience of this country and I only feel it a little painful that the other acting Archbishops and Bishops have not taken the opportunity of openly supporting you in a matter which concerns them too. In any case, at a time when the political leaders are obviously not able to see the implications of their policy it is a comfort to know that there are in this country personalities who have the courage to stand up against public opinion and to warn the nation in a truly prophetic way of the dangerous road they are taking.

Gerhard Leibholz to George Bell, 14 February 1944

The George Bell-Gerhard Leibholz Correspondence

In the Long Shadow of the Third Reich, 19381958

Edited by

Gerhard Ringshausen and Andrew Chandler

Contents

The editors are glad to acknowledge with gratitude a gift from the late Hans Florin and his wife, Ev. It is this that has made possible the publication of the complete correspondence of George Bell and Gerhard Leibholz.

We remember with gratitude Marianne Leibholz, who kept her fathers letters to George Bell for many years and gave permission for their publication, and who died in Gttingen on 30 January 2017.

We owe much to the kindness of the archivists and librarians of Lambeth Palace Library in London and of the Bundesarchiv in Koblenz. We also wish to thank the staff at the World Council of Churches archive in Geneva and the Evangelisches Zentralarchiv in Berlin. We are also grateful to the librarians at Leuphana University of Lneburg and the University of Chichester for their continuing support.

Gerhard Ringshausen thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for a grant to support his research work in Lambeth Palace Library.

We are truly grateful to Rhodri Mogford, our admirable editor at Bloomsbury, and to the meticulous, and patient, staff at Bloomsbury.

It is a pleasure to express our continuing gratitude to our wives and families, to Ellen Ringshausen in Lneburg and to Alice Chandler in Tangmere.

At the end of August 1938 the bishop of Chichester, George Bell, received a letter from his German friend, the young German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer. By this time they had come to know each other well, as friends but also as fast allies. Their paths had first crossed at a meeting of the Universal Christian Council for Life and Work in Novi Sad at the end of 1933, but it was when Bonhoeffer had come to London to be the pastor of a German congregation in Forest Hill that their relationship had assumed a far greater importance in the context of the unfolding German Church Struggle. This was now an intimate connection which showed the many proofs of a personal rapport and a creative moral affinity.

Before 1933 George Bell had cultivated close links with German theologians and scholars both within the contexts of the Life and Work movement, in which he had soon become a leading light, and within an occasional, though purposeful and productive, series of Anglo-German exchanges between 1927 and 1930. While these expressed an emerging ecumenical consciousness they also represented a contribution to the ongoing labours of men and women of goodwill in both Britain and Germany to foster the harmony of two nations only recently embroiled in a catastrophic war. It was a war in which George Bell had lost two brothers.

Bell was no Germanist: he did not speak or read German and his sense of German theology, philosophy and thought at large was not profound. But if the interior theological world of German Protestantism remained, to a certain extent, obscure to him, a public crisis of Church and State was something that he, like many other British Christians, intuitively recognized. Bell was in no doubt that this is what he saw at work in Germany after January 1933, the month which brought Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist movement to power. Four days after Hitler had been appointed chancellor of a coalition government, and on Bells fiftieth birthday, the Executive Committee of the Universal Christian Council for Life and Work met in Berlin. It is difficult not to wonder at the conversations which must have occurred between the formal sessions of this gathering. For already the atmosphere was one precariously poised between moods of popular excitement and of public dread. National Socialism had many admirers in provincial life, but many critics in Berlin itself, a diverse, creative city which would never be profoundly reconciled to its principles or manifestations. Bells first impressions of National Socialism were early ones, and vivid ones too.

The National Socialist state almost at once threw up a plethora of new, and often intense, fears, and not only in Germany. Across Europe observers viewed the coming of this new power as a danger to the security of nations and also a threat to the idea of democracy at large. For all its protestations of national revolution, the fundamental reality of the new regime was that of persecution: of political opponents, of pacifists and, above all, of Jews. Unscripted acts of hostility by party zealots were now purposefully reinforced by legislation passed by a new, supportive Reichstag. On 21 March 1933 a Malicious Practices Act was passed to license the detention of critics. On 1 April 1933 a boycott of Jewish businesses was imposed. In the same month the Reichstag passed the law for the Restoration of the Civil Service which removed from their positions all German Jews. It would be the first of a succession of Aryan paragraphs which would seek to classify Jews as full or half non-Aryans and enforce discrimination against them across German society. In April 1933 limits were imposed on the number of places allowed to Jewish students in German universities while Jews working in the medical or legal spheres faced growing penalties and even found that they could no longer practice at all. In the new climate further laws against German Jews accumulated across the provinces. Such measures identified and ostracized countless numbers of what had until 1933 been a secure and prosperous middle class. It was inevitable that thousands of German-Jewish families began to ask if they had a future in Germany at all. The numbers of those escaping into exile began to rise.