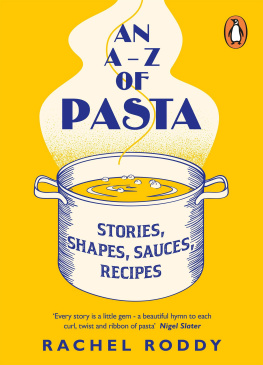

Rachel Roddy describing how to boil potatoes would inspire me. I want to live under her kitchen table. There are very, very few who possess such a supremely uncluttered culinary voice as hers, just now.

Simon Hopkinson

This very entertaining book is a perfect marriage of the personal with the practical. Rachel has the ability of combining intimate reminiscences with excellent recipes. If you want to know anything about the food of Rome or Sicily, this is the book for you.

Anna del Conte

Rachel Roddy brings the warm flavours of the south into our northern kitchens. Her dishes from Sicily and Rome are linked by family stories, and both place and food are beautifully photographed. I shall cook from this book with pleasure.

Jill Norman

Roddys writing often reminds me of a more generous, more evocative Elizabeth David.

Nancy Harmon Jenkins, The Art of Eating

Rachel Roddy writes a weekly column for Guardian Cook. Her first book, Five Quarters, won the Andr Simon Food Book award and the Guild of Food Writers First Book award. Rachel lives with her partner, Vincenzo, and son, Luca, near the food market in Testaccio, a distinctive working-class quarter of Rome, and spends part of the year in Vincenzos family house in Gela, south-east Sicily.

racheleats.wordpress.com  @racheleats

@racheleats  @rachelaliceroddy

@rachelaliceroddy

CONTENTS

Like the rest of the house, the kitchen blind had been closed for 15 years. I tugged the strap down hard. At first the blind jolted up but then, instead of continuing to roll up as a single sheet, the plastic sections collapsed back down one by one, as fast as an automatic rifle. Light streaked in, momentarily blinding me and illuminating both the room and the clouds of dust the blind had released. As it settled, the kitchen I had heard so much about revealed itself. It was my partner Vincenzos grandparents kitchen in Gela, on the south coast of Sicily, and the place he has always considered home. It was larger than I had imagined six metres by four with a low sink, a single arching tap above it and a curtain below, a small gas stove, a narrow work surface, and at one end a hatch through to a dining room of the same size. Two floors above me, Vincenzo and his cousin Elio were trying to get the motor for the water pump going on the flat roof, its wheezing attempts like a flat car battery, while my then-three-year-old son, Luca, ran around the house collecting more dust. This was in May 2015.

I had first visited Sicily ten years earlier, an impulsive trip with no luggage and no real plans other than a vague idea about finding a Caravaggio and a volcano. I began travelling clockwise around the circumference of island, mostly by bus. It was March. It was warm and the air so full of spring I could almost taste it. The bus, skirting the coast, cut between rich blue sea and the island itself, expansive, muscular and profoundly green. I caught my breath. The journey felt more important than the stops: Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, Lascari, Messina, Taormina, Catania, Syracuse, looping inland to Enna. In a museum in Messina I found the Caravaggio, two in fact, and later, in Catania, a city that seems carved out of volcanic lava, I took a chair lift and inadvisably walked up to the snowy peak of Etna. It was also in Catania that I discovered that almond granita and warm brioche is considered a normal and ordinary way to start the day. I also noticed a flat for sale near the fish market.

The idea of replacing my London flat with that one taunted me. It was fanciful thinking but, reflecting back twelve years later, its clear that this was the moment when I knew I would stay in Italy, realization solidifying into resolve as I walked and walked. I didnt buy that flat; instead, I decided to go to Rome to learn some Italian. As it turned out, a part of Rome called Testaccio stuck a foot out and tripped me up with its easy charm. In a way, I found Sicily in Rome when I met Vincenzo, and we settled in to life in Testaccio, a quarter that feels more like living in a small provincial town than part of a capital city.

Living with a Sicilian, though, and one whose love of the food of home is deeply rooted, brought a rich culinary vein of tomatoes and oranges, ricotta and oregano, of dishes invested with the warmth of Sicily. Vincenzos parents also lived in Rome and were quietly traditional in the way they ate, certain flavours as omnipresent as their lapses into Sicilian dialect. I became accustomed to flashes of Sicilian genius: wedges of lemon with everything, breadcrumbs on pasta, the perfume of saffron, pasta with sardines and aromatic wild fennel, swordfish and aubergine, orange and fennel salad, salted ricotta, pine nut and raisins in places I might not expect; and to the fact that every important occasion was marked with a triumphantly Baroque cake called cassata, or custard topped with hundreds and thousands.

Ask someone to show you how to cook something and theres a good chance you will get more than just a recipe. Recipes live in stories: small everyday ones and much bigger ones. Vincenzos mother, Carmela, passed on her recipes to me along with pieces of family history that I might never have discovered otherwise. Each dish felt like a portal into their life, both in Sicily and away from it, where recipes became a way of preserving, remembering, and being transported.

What food do you pack in your suitcase when you go away? Like many immigrants, the movement of food became central to my life when I moved away, a clear reminder of here and there. Each time I went back to the UK I would take back pieces of my new life: pasta, Parmesan, pecorino, peperoncino and guanciale. Then, on my return, Id fill my suitcase with baking powder, marmalade, Yorkshire tea, Marmite, fruit cake, Lancashire cheese, Polo mints and leaf gelatine. Vincenzos parents first left Gela when he was a boy, and the Sicilian food they took with them was a tangible link to their home region. His grandmother, Sara, who stayed in Gela, may have missed her daughter and grandchildren, but at least she knew they had plenty of her salsa (tomato sauce).

For most Italians, Gela is now defined by two things: the mafia and the monstrous oil refinery that was built there in the 1960s. Vincenzo likes to tell a story about being at a dinner party where two Sicilians from Catania, on hearing a mention of Gela, laughed and said devi andare a Gela, per vedere quant brutta (you have to go to Gela just to see how ugly it is). Once or twice I have met a historian whose eyes have lit up at the thought of ancient Greek Gela, but guide books advise you to drive straight past. Like a child being told not to do something, though, all this just fuelled my curiosity. I was curious to see Gela, to understand. At the same time, although we had lived in Rome for ten years, Sicily had deeply influenced the way we cooked and ate. Occasional visits had provided feasts of the flavours we both craved, but our day-to-day life was Roman. Sicily was always bubbling just below the surface, though, for Vincenzo, whose attachment to his place of birth, and to its food, is powerful, but for me too. Then: Why dont you go and spend some time in

Next page

@racheleats

@racheleats  @rachelaliceroddy

@rachelaliceroddy