Published in 2009 by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London SW11 6SS

www.grubstreet.co.uk

Copyright this UK edition Grub Street 1999, 2009

Text Copyright Mary Taylor Simeti 1989, 2009

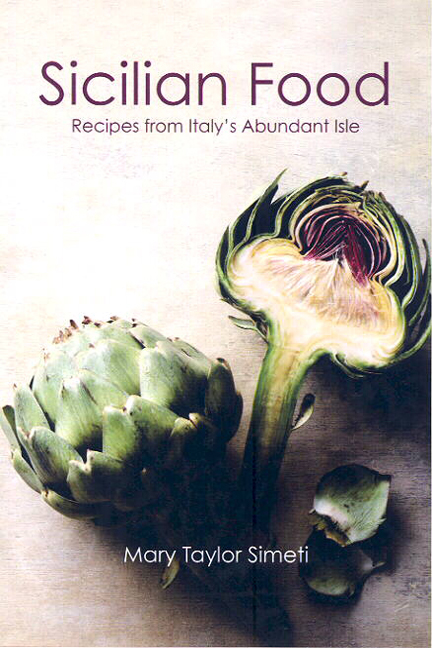

Cover design LizzieBdesign

This book was first published as Pomp and Sustenance: Twenty-Five Centuries of Sicilian Food in the USA by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1989.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Simeti, Mary Taylor

Sicilian food

1. Cookery, ItalianSicilian style

I.Title

641.59458

ISBN 978-1-902304-17-5

eISBN 978-1-908117-91-5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission of the publisher.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material.

Doubleday: Excerpts from Homer, The Odyssey , translated by Robert Fitzgerald. Copyright 1961 by Robert Fitzgerald. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

Garzanti Editore S.p.A.: Excerpt from the English translation of The Viceroys , by Federico De Roberto, published in 1972 by Garzanti Editore, Milano. Reprinted by permission.

Pantheon Books, Inc.: Excerpts from Two Stories and a Memory by Giuseppe di Lampedusa, translated by Archibald Colquhoun. Copyright 1962 by Wm. Collins Sons and Co., Ltd., and Pantheon Books, Inc.; and excerpts from The Leopard by Giuseppe di Lampedusa, translated by Archibald Colquhoun. Copyright 1960 by Wm. Collins Sons and Co., Ltd., and Random House, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, a Division of Random House, Inc.

Sellerio Editore: Translation by Mary Taylor Simeti of a brief excerpt from Pani e dolci della Sicilia by Antonio Uccello, published by Sellerio Editore, Palermo, 1976. Reprinted by permission.

George Weidenfeld & Nicholson Limited: Excerpts from The Happy Summer Days by Fulco di Verdura. Reprinted by permission of George Weidenfeld & Nicolson Limited, London.

Illustrations reproduced from 1989 edition with thanks.

Printed and bound in India

Contents

Preface

I learned to cook in Sicily. Fresh out of an American college and living in a small Sicilian town on a volunteers stipend of $75 a month, I had no alternative. So I put together what I remembered from watching the black cook from Virginia who had nourished me in my childhood and what I learned from my fellow workers at Danilo Dolcis centre for community development, and I came up with a motley repertoire of dishesAmerican, Tuscan, Umbrian, Piedmontese, even Swiss and Swedish. I was willing to try anything as long as it was cheap.

Marriage into a Sicilian family did not give my food the focus one might have expected. My mother-in-laws cooking was so circumscribed by her husbands diabetes and her own ill health that it included little that could have been identified as typically Sicilian. Though I enjoyed the elaborate pastas and desserts that she or the other women in the family produced for special occasions, my own celebrations tended toward roast turkey with stuffing, apple pie, gingerbread men, and other props for my precarious cultural identity. Meanwhile, the first spores of feminism were swelling inside me like a potent but as yet unidentified yeast, and the sheer quantity of maintenance cooking required in a society in which the whole family eats all three meals at home discouraged me from spending more time or energy in the kitchen than was absolutely necessary.

I came late, therefore, to exploring Sicilian cooking as a regional cuisine, and to grasping its particular characteristics, and I did so by way of a back door. In the early seventies my husband and I restored his family farm and began to spend our summers in the country. It was there that I learned how olives are gathered and pressed into oil and how grapes mature and become wine, and there that I talked to shepherds as they made ricotta and to peasant women who were bottling the years supply of tomato sauce.

As I entered the world of Sicilian peasants, I discovered that their culture has very little future but a very ancient past. What I learned on the farm rekindled my college love of history and sent me, once freed from the demands of small children, to the former convents and palaces where Palermos libraries are housed, in surroundings so picturesque that they can almost compensate for inadequate catalogues and irretrievable books.

Weekday mornings at a library, tempered by weekends on the farm, gave me the eccentric vision of food from which this book stems. I discovered that food in Sicily shares in what I have come to regard as the terrible density of Sicilian culture, an insular culture compacted by centuries of foreign conquest and domestic oppression. Although daunting when it immobilises the island in the face of its ills, this density of history and tradition is fascinating and deeply satisfying when it informs and gives substance to the actions and rituals of every dayto the catching of fish and the gathering of fruit, to the kneading of daily bread and the preparing of festive pastries.

I must confess that I lack the scruples of a proper historian. My bookish browsing has taken me far afield, to pastures and periods I know nothing about, and I have rushed in where scholars would barely dabble a toe, noting coincidences and making connections with only the frail cement of supposition. Scholarly or not, my reading has given me great pleasure and amusement and has introduced my palate to some novel tastes: to the exotic aromas of earlier epochsancient Greek, Arabic, and Normanand to the familiar yet often unrecognised ingredients of more recent times, those of hunger and faith, of pride and jealousy and joy.

I have come to hypothesise that most of the basic ingredients and techniques of contemporary Sicilian cooking were introduced to the island by the end of the twelfth century. At that point there appears to have been a change in dynamicsfrom a chronological development determined by external forces to a series of parallel developments in which internal economic considerations play the greatest role in modifying and diversifying the Sicilian diet. The structure of this book reflects that change. The first two chapters deal with the period before 1200, with the classical era and what it is possible to reconstruct of Sicilian cooking under the Greeks and the Romans, and then with the innovations that came with the Arabic and the Norman invasions. After 1200 class rather than conquest is the determining factor. Thus the third chapter is about the peasantry: what sustained them during centuries of increasing poverty and was consequently sacred to them. The fourth chapter is dedicated to the food with which the peasantry celebrated, either in festive contrast to their privations or as a daily reaffirmation of their passage to the middle class. explores what food meant to the aristocracy, who were concerned with status rather than survival. Special categories of Sicilian food occupy the last three chapters: the confections and the pastries produced by the islands convents, the food available in the street and on the road, and finally the particular Sicilian passion, ice cream.