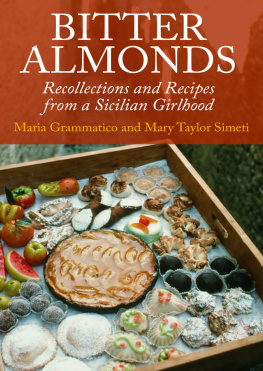

Bitter Almonds

Recollections and Recipes from a Sicilian Girlhood

Maria Grammatico & Mary Taylor Simeti

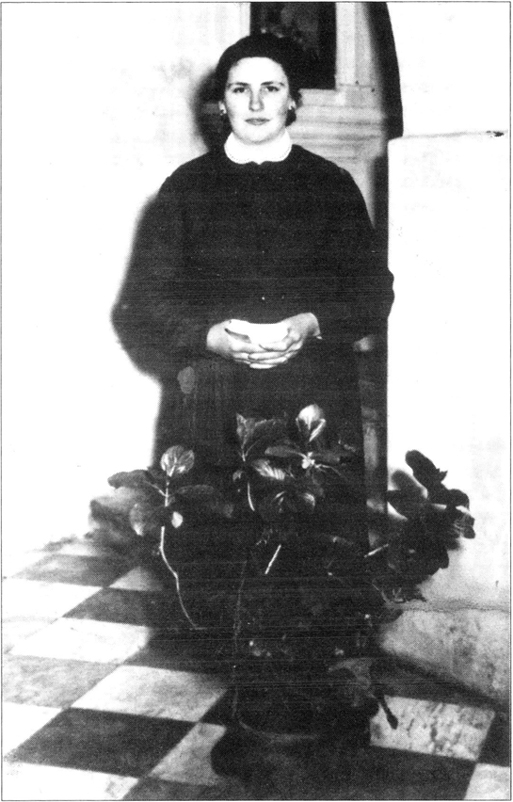

Maria at the Istituto San Carlo, circa 1959

Facciamo tutto a mano, partendo dalle sostanze naturali, dal latte, dalle zucche, dalle mandorle, ai pistacchi. I costi delle materie prime oggi sono proibitivi ed esigui sono i margini di guadagno. Svolgiamo questa attivit per tenere aperta una finestra, sia pure protetta da grate, sul mondo che non ci ostile e che dobbiamo pur amare.

We do everything by hand, starting with natural ingredients, from the milk and the squashes to the almonds and pistachios. The cost of the raw materials today is prohibitive, and the margins of profit are very narrow. We continue this activity so that we may maintain a window openalbeit protected by an iron grateon the world, which is not hostile to us and which we have, after all, to love.

From an interview with a Benedictine nun,

Palermo, Il Giornale di Sicilia, 5 October 1981

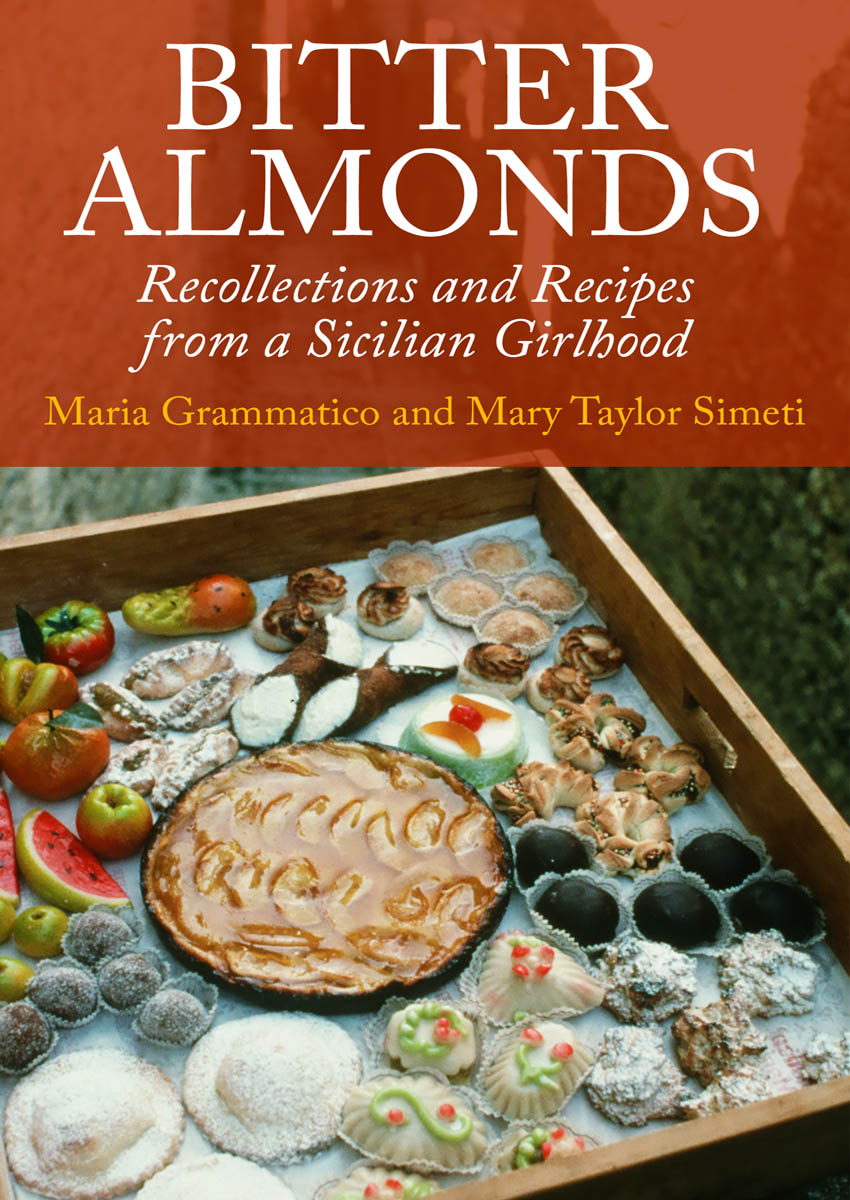

Contents

A fresh almond pastry, dusted with powdered sugar or coated with chocolate, has been a part of every trip to Erice for almost as far back as I can remember. I couldnt have eaten one on my first visit, of course: when I came to Sicily in 1962, just out of college and ready for a year of volunteer development work, Maria Grammatico was still closed up in the Istituto San Carlo, the convent-like orphanage where she spent all of her adolescence. Her pastry shop didnt exist, and I didnt know enough then about Sicily to realize that there were convents where you could give your order to a dim figure behind an iron grate and place your money upon a wheel, a revolving hatch that slid the coins through the wall and brought out pastries in their stead.

It was an austere world that I encountered upon my arrival in Sicily. The first half of the twentieth century had done little to leaven the extreme poverty bequeathed by centuries of foreign conquest and domination, a poverty that, if anything, had been exacerbated by the economic policies of the Fascist regime and by the Second World War. If the city of Trapani, the major seaport on the west coast of the island, had undergone a degree of modernization in the preceding decades, followed by a degree of bomb damage during the Allied invasion in 1943, in the lonely farms of Trapanis hinterland and in the little town of Erice, hovering on a mountaintop above the city, little had changed. Daily life continued much as it had in the nineteenth century.

In the early 1960s the effects of the economic boom that was transforming Northern Italy were just beginning to trickle down to Sicily. In subsequent years, a wave of prosperity and modern technology descended, altering the face of the countryside and rendering the inhabitants of Sicilys towns and cities more or less indistinguishable from anyone else in Southern Europe. The world in which Maria Grammatico had grown up all but disappeared.

The story behind the almond pastries was slow to reveal itself. In an account of a trip to Erice in the early 1980s, I wrote in passing of purchasing Erices special almond cakes in a pastry shop just off the main square but devoted much more space to describing the classical origins and the abundant flora of this medieval village, whose spectacular location, on the top of a solitary mountain that rises 2,400 feet above the coastal plain, has inevitably attracted myth and speculation. Thucydides claimed that Erice and her sister city, Segesta, were founded in the twelfth century BC by Trojans escaping from the fall. These descendants of neas became known as the Elymians, and they were one of the three peoples that inhabited Sicily when the Greeks began to colonize the island in the eighth century BC .

Archaeological data confirm the Eastern Mediterranean, most probably Anatolian origin of the Elymians, but as of yet, nothing has been found that establishes the date of their arrival in western Sicily. It is probable, however, that they found a goddess already installed. The Great Mother of the Mediterranean Basin has been worshipped at Erice since time immemorial. The Carthaginians called her Astarte; the Greeks knew her as Aphrodite, and claimed that the lady had risen from the waves just below the sacred mountain, had lain on its slopes with an Argonaut, Butes the Beekeeper, and had given birth there to the king of the Elymians, Eryx, whose name means heather. Daedalus dedicated a honeycomb wrought of gold to Aphrodites altar at Erice, and the Romans lay with sacred prostitutes at the shrine of Venus Ericina.

It is to be expected that so ancient a tradition would be slow to die, yet it is nonetheless astonishing to read that vestiges of the pagan cult were still to be found in the sixteenth century. A document dated 1554 states that the mid-August festivities in honour of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary were established by papal order to distract the large flow of people coming to the temple of Venus. In the second half of that century, a portrait of the Virgin was miraculously saved from a shipwreck and placed in the nearby town of Custonaci, and in the following years the Madonna of Custonaci gradually displaced Aphrodite as the patron saint of Erice. There are those who claim that something still persists: Erices traditional wedding biscuits, known as miliddi, are said to descend from mylloi, the ritual cakes sweetened with honey and sacred to the goddess that are described in the poetry of Theocritus.

My curiosity about the later periods of Erices history was whetted by a 1985 trip to see I Misteri, the Good Friday processions that take place on a grandiose scale in Trapani, and on a much smaller, more intimate scale in Erice itself. Here my sister and I followed the almost life-sized statues representing the Passion of Christ and the Sorrows of the Madonna, a Renaissance reworking of the mystery plays of the Middle Ages, through narrow cobbled streets, past abandoned churches, medieval houses, and baroque mansions. The mist that floated in from the Mediterranean, curling under the arches and around the bell towers, seemed to cut us off from the modern world below and project us backwards in time to the period of Erices second flowering, when the town became known as Monte San Giuliano. (The classical name was restored by Mussolini.) Almost completely deserted in the Byzantine and Arab eras, Erice owed its rebirth and subsequent wealth to the lands assigned to it by the Norman King William II in the twelfth century, a grant reconfirmed in the following century by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. These vast communal territories, which were not carved up definitively until the middle of the nineteenth century, nurtured a flourishing middle class, which built itself miniature mountaintop palaces in which to escape the heat of the Sicilian summer. Hoping perhaps to escape the heat of eternal perdition as well, it also endowed some forty-two churches and a number of convents and orphanages. Yet the prosperity of Monte San Giuliano did not survive the dismembering of its territory. The buildings still stand, but the doors of many are boarded up and their roofs are falling; only a handful of resident faithful remain to follow Erices processions.

The Good Friday procession disbanded just a few steps from Marias pastry shop. We entered in search of something to warm us up and were greeted by a counter full of marzipan lambs. Unlike most of the paschal lambs on sale throughout Sicily at Eastertime, which are made in standard moulds that vary only in size and portray the lamb sitting in a grassy pasture, Marias lambs were lying down. Eyes open, tongues hanging out a bit, fleece beautifully executed curl by curl, they gave little clue to the fact that they represented the sacrificial, slaughtered lamb.