Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To the memory of my mother, Ruth Porter Tall Chief, whose indomitable spirit, perseverance, and sense of discipline led the way

T HERE ARE MANY people without whom this book could not have been published.

I am grateful to my good friend Francis Mason of Ballet Review for introducing me to Larry Kaplan who wrote the book with me, and I would like to thank my fellow Chicagoan Bobbie Goldblatt who always encouraged me to write about my life. I also want to express thanks to my agent, Faith Hamlin, for her enthusiasm and for bringing the project to Henry Holt.

I especially want to thank my editor, John Macrae, for his invaluable editorial guidance and advice, and also thank Rachel Klauber-Speiden for her splendid work on the manuscript.

As always, I am deeply grateful to my husband, Buzz, for his unfailing and unending support, and to my daughter, Elise, for reading the book and offering suggestions.

My collaborator and I offer our appreciation to the Balanchine Trust and to Don Daniels and Marvin Hoshino of Ballet Review, and Marilyn Annan, Linda Hetzer, and George Tall Chief who helped us complete research.

Symphonie Concertante, Swan Lake, The Nutcracker, choreography by George Balanchine The George Balanchine Trust

Orpheus, choreography by George Balanchine

Firebird Jerome Robbins

Balanchine is a trademark of the George Balanchine Trust.

New York City, 1983

W ALKING ALONG THE corridor in Roosevelt Hospital to Balanchines room I was agitated and upset, distressed over his condition. I knew George was failing, but wasnt sure what to expect. For most of his life, despite hardships he had suffered as a young man in Russia and a bout of tuberculosis in Paris in 1931, he not only enjoyed good health, he seemed indestructible. Now, unbelievably to me and to everyone who loved him, George was dying.

He was admired as the greatest choreographer of our timeperhaps of all time. It was his knowledge of what I could do as much as anything on my part that had made me a prima ballerina. He guided me my whole life, not only when I danced for him and during our marriage. I couldnt imagine the world without him.

When my husband, Buzz, and I entered his room, George didnt seem to notice us. The tiny transistor radio by his bed was playing music. He was lying on his back staring into space, holding his hands up above his head and tapping the tips of his fingers together in time to the music. His face was gray, his cheeks hollow, his eyes sunken. On his wrist was the turquoise-and-silver American Indian bracelet my cousin Helen Tall Chief Robertson had given him when he and I visited my family in Fairfax, Oklahoma, a few years after our wedding forty years earlier.

My husband and I stood silently at Georges bedside. Because he was unaware of our entrance, it was a minute before a tender smile brightened his face.

Ah, you see, Maria, he said in a whisper as he turned his head to me. I am making steps.

Moving our chairs close to his bed, Buzz and I sat down. Georges nurse was standing nearby as if on alert. In an attempt to sit up, George shifted his position, trying to get comfortable. Then he turned to Buzz and seemed to be saying his name.

I was very surprised. In all the years theyd known each other, George had never addressed my husband by name. Henry, Buzzs real name, doesnt exist in Russian. Genri would be the closest approximation. George wasnt comfortable using a nickname so he never called Buzz anything. Until now.

Buzz, he was saying softly. Buzz leaned closer, and George whispered something in his ear. We could hardly hear him. The nurse asked him to repeat it, and suddenly it became clear.

Buzz, if you ever have any trouble with Maria, you just come to me.

Did you understand him? the nurse asked.

Did I understand him? I certainly did, I said. George! How could you say such a thing?

I looked at him, expecting that wed all share a laugh. But Georges eyes had clouded over. He was already drifting away, his head falling back on the pillow.

The nurse looked at us, her eyes giving a command: It was time to leave. I forced myself to murmur an unheard good-bye, stroked Georges arm, and walked out the door. It was the last time I would see him alive.

A golden age of ballet had taken place in New York City, and George, almost single-handedly, was responsible for its glory. I was part of it too.

With his death, an incredible dance epoch was ending. What would it mean for the future of ballet? How could the art form he revolutionized exist without him? And what would happen to the company George created, considered one of the greatest classical troupes in history? How would his dancers carry on without his guidance and his genius?

Imagining the future was unbearable. All I could do was to try to summon the past.

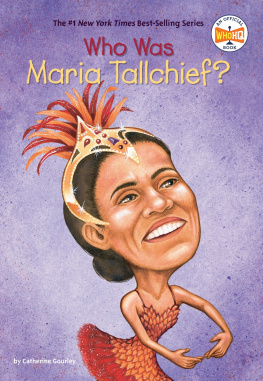

M Y FATHER , A LEXANDER Joseph Tall Chief, was a full-blooded Osage Indian. Six foot two, he walked with a sturdy gait and loved to hunt. The story goes that he could stroll through the woods, rifle in hand, spot a quail or pheasant out of the corner of his eye, point the gun, and shoot the bird without breaking his stride. With his strong aquiline profile, Daddy resembled the Indian on the buffalo-head nickel. Women found him handsome, and when I was young I idolized him.

My earliest memory of my father is from when I was three. I slept in a second-floor bedroom with my sister Marjorie, who was an infant. One evening when I fell asleep in the living room, Daddy picked me up. Snuggled in his arms, I remember waking as we climbed the stairs. I can still see his dark eyes, his tender smile, his shiny black hair.

When Daddy was a boy, oil was discovered on Osage land, and overnight the tribe became rich. As a young girl growing up on the Osage reservation in Fairfax, Oklahoma, I felt my father owned the town. He had property everywhere. The local movie theater on Main Street, and the pool hall opposite, belonged to him. Our ten-room, terra-cottabrick house stood high on a hill overlooking the reservation.

When my father was a young man, he married a young German immigrant and they had three childrentwo boys, Alexander (whom everyone called Hunky) and Tommy, and a girl, Frances. They were little children when their mother died. Later, when Ruth Porter, my mother, came to Fairfax to visit her sister, who worked as a cook and housekeeper for my Grandma Tall Chief, Daddy was Fairfaxs most eligible bachelor. Mother must have arrived tired and dusty from her long journey, but from what Im told there was an instant attraction between them.

Mother was born in Oxford, Kansas. A determined woman of Scots-Irish blood, she was beautiful, with light brown hair, gray eyes, and delicate features. My tall and lanky father and my tiny mother made an odd couple physically, but they were very much in love. As soon as they married they started a family, and Daddys children from his first marriage went to live with Grandma Tall Chief, who brought them up in her house at the bottom of the hill.

I was born in Fairfax in the tiny local hospital on January 24, 1925. The doctor mishandled the forceps, leaving a large red mark on my forehead. Otherwise, I was healthy and normal. They named me Elizabeth Marie after two grandmothers: Eliza Tall Chief, and my Grandma Porter, whod been named for Marie Antoinette, and with whom I would spend a great deal of time as a child. They called me Betty Marie.