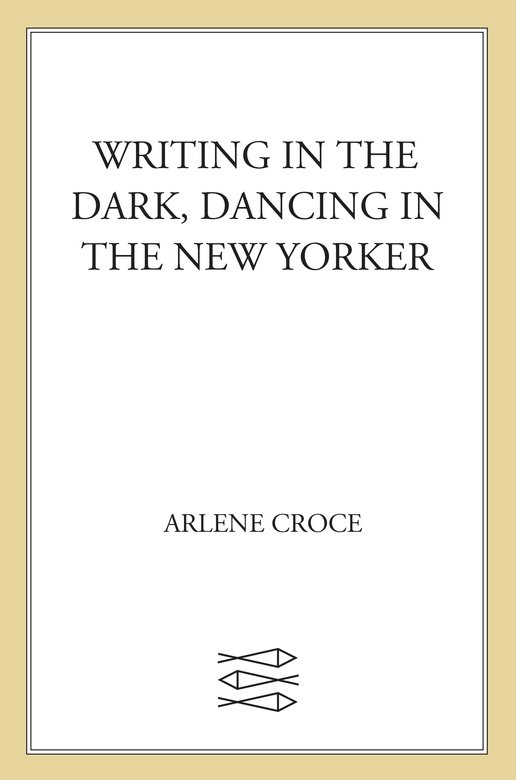

Looking back over the events covered in these pieces, I can hardly believe they happened. That dance could ever have been as rich, as varied, and as plentiful as it was in the seventies and eighties now seems a miracle. When I was appointed The New Yorkers dance critic, in 1973, I knew the hour was late: Balanchine was sixty-nine, Graham had left the stage, and any number of important careers were winding down. Still, there was enough activity to keep anybody interested, and what with Baryshnikovs defection in 1974 and Suzanne Farrells return from exile that same year, there was more than I could keep up with. I was in the theatre nightly and sometimes, between Friday night and Sunday evening, I saw five performances. Companies often played side by side, and it was nothing to dart from one theatre to another and back in the course of a single performance.

The dance season had always been a congested affair. In my time, it reached such levels that I invented something called Ballet Alert, a fictitious telephone service for hyperactive balletomanes, and was taken seriously. This was probably because Ballet Alert was printed in Dancing, myregular space in The New Yorker , and not in the front of the book where the casuals were. I should have warned my editors that I was perpetrating a hoax. William Shawn was not amused. I had broken an inflexible New Yorker rule: critics do not write humor.

But of course Ballet Alert was also a joke on The New Yorker my parody of a Talk of the Town piece. To me it was so obviously parodic, and so patently silly (Cynthia Gregorys shredder?), I never thought it would be believed. But perhaps I underestimated the special idiocy which outsiders attached to the ballet boom, a term invented by the media to cover their own delayed recognition of the ballet scene. In actuality, the boom had been going on since the thirties; by the late sixties, ballet was an accepted part of American culturea covertly accepted part. Youd go to a party; if someones eyes lit up at the mention of Balanchines name, youd made a friend. The excitement of balletgoing in New York was an undercover excitement. The outside world seemed to have no inkling of what was going on; it still thought that the balletgoing public consisted of little girls, mothers, homosexuals, foreigners, and outright nuts like my invention Carmel Capehart. A glance at the audience on an average night at the New York City, the Royal, or the Bolshoi Ballet would disprove the truth of this. Even Martha Graham drew a normal Broadway-theatre-going audience. Today, of course, as many kinds of people go to dance performances as play tennis, another aristocratic pastime of my youth. As for the ballet boom, the reader can judge the reality of it by the number of boomlets it inspired in the seventies aloneBournonville, regional ballet, drag ballet, and that unique product of the times, the post-modern ballet.

The term post-modernism has an extra semantic layerin dance: it means not only after modernism but after the modern dance. Post-modern ballet is a hybrid that came about when the ballet and the modern dance ceased to be hostile campsideology was dying out along with creativityand began embracing each other. The ballet companies, with their rising popularity and longer seasons, needed choreographers, and because choreographers had yet to come forth from the academy in sufficient numbers, they came from the modern and post-modern dance. To Twyla Tharp, Laura Dean, Mark Morris, and a host of other young nonclassical choreographers, a ballet-company commission meant prestige, which meant bigger grants for their own companies from a new government agency, the National Endowment for the Arts. To ballet dancers like Nureyev and Baryshnikov who knew nothing of the ideological warfare in American dance, fraternizing with the moderns meant a chance to learn new techniques, which enabled them to extend their careers. A fair number of the premires I reviewed were of post-modern ballets, a development I took for granted at the time but now see as symptomatic of the forces that were struggling against depletion in the seventies and eighties. They are still struggling; the energy of the American dance renaissance that began in the thirties is not completely spent, but that post-modern ballet is a twilight (I almost wrote Twylight) phenomenon I have no doubt.

Another thing that has changed, of course, is The New Yorker ; its whole style was different in Shawns day. The amount of freedom a writer enjoyed there may have been unique in American journalism. I never wrote on assignment, was never asked to cover this or that eventcoverage as a conception did not exist. Once it was conceded that dance was a topic acceptable on a regular basis to NewYorker readers, my choices of subject and deadline were never even queried. When I thought I had to write, I would reserve space, then file at the last minute. When, as frequently happened, I overran the space, more space was found. And The New Yorkers editing procedures were a model of courtesy and scrupulosity.

But even though my options as a practicing critic were practically limitless, my capacities still werent enough for my subject. It seemed that in those days I could never write as much as I had seen I mean in depth as well as diversityand every deadline was an opportunity missed. I realized that what I wrote was always going to be at a certain remove from the actual experience-I believe it was Merce Cunningham who said that speaking about dance is like nailing Jell-O to the wallbut getting comfortable with that distance took some doing. It required accepting a possibility of success based on an inevitability of diminution. In the course of writing about a dance, you invariably diminish it; you change its nature. It becomes, or aspects of it become, utterable, therefore false. It is a real temptation to a dance critic to prolong the illusion of utterability; art is, after all, a world of semblanceseven dance tolerates falsity to an extent. However, if you get to where the reader is saying to himself, I guess you had to have been there, you have gone past the point of toleration.

Did I take notes? Yes and no. Mostly I took them if I felt my attention wandering, but I found it better, if I possibly could, to force my concentration in the hope of finding an afterimage later. It is the afterimage of the dance rather than the dance itself which is the true subject of the review. To let an afterimage form, one has to give the stage ones full attention, without the distraction of note-taking. This, the greatest lesson I absorbed from the master, EdwinDenby, was too strict to adhere to if it happened to be the weekend, I had to file on Tuesday, and I was not in my freshest mind. I evolved a method of minimal, disciplined, and, I hoped, risk-free note-taking, using a small memo pad on which I could get no more than two or three notes a page. It was okay when it worked. A white label pasted on the front cover was supposed to guard against getting the pad upside down in the dark, and by moving my thumb down the page, covering what Id just written, I could at least hope not to scrawl one note on top of another. After the performance, I would jot the title and date of the event on the white label. I filled whole shelves with such pads in the course of a season, and I doubt that I consulted more than two or three of them when it came time to write the reviews. Some image would by then have formed, not necessarily an afterimage, but a cumulative impression more suggestive than Jumps like a seal or Off the music? In the end, all note-taking was good for was recording visual facts, like the color of costumes and the sequence of events, which I had trouble remembering. It made New Yorker fact checking easier.