Published in 2016 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2016 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2016 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Nicholas Croce: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Cindy Reiman: Photo Researcher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Anthropology / edited by Nicholas Croce. First edition.

pages cm. (The Britannica guide to the social sciences)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-6227-5541-7 (eBook))

1. AnthropologyJuvenile literature. I. Croce, Nicholas.

GN31.5.A67 2016

301dc23

2015017002

Photo Credits: Cover, p. 1 marigold_88/iStock/Thinkstock; p. vii 1994 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.; p. ix Miguel Rojo/AFP/Getty Images; p. xii Vanderlei Almedia/AFP/Getty Images; p. xiv Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty Images; p. 1 Paul D. Stewart/Science Source; p. 4 Marco Di Lauro/Getty Images; p. 8 Eric-Paul-Pierre Pasquier/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images; p. 12 Marc Gantier/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images; p. 15 Anchorage Daily News/Tribune News Service/Getty Images; pp. 19, 23 Science Source; p. 26 AP Images; pp. 40-41 STR/AFP/Getty Images; p. 45 John Reader/Science Source; , 64-65, 100 AFP/Getty Images; p. 69 Kevin King/Moment/Getty Images; p. 71 Keren Su/China Span/Alamy; p. 72 Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images; p. 84 De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images; p. 88 Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy; p. 108 Bloomberg/Getty Images; p. 114 ullstein bild/Getty Images; p. 117 Sovoto/Universal Images Group/Getty Images; p. 122 Hoberman Collection/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

CONTENTS

T he science of the origins and development of human beings and their cultures is called anthropology. The word anthropology is derived from two Greek words: anthropos meaning man or human and logos, meaning thought or reason. Anthropologists investigate the whole range of human development and behavior, including biological variation, geographic distribution, evolutionary history, cultural history, and social relationships.

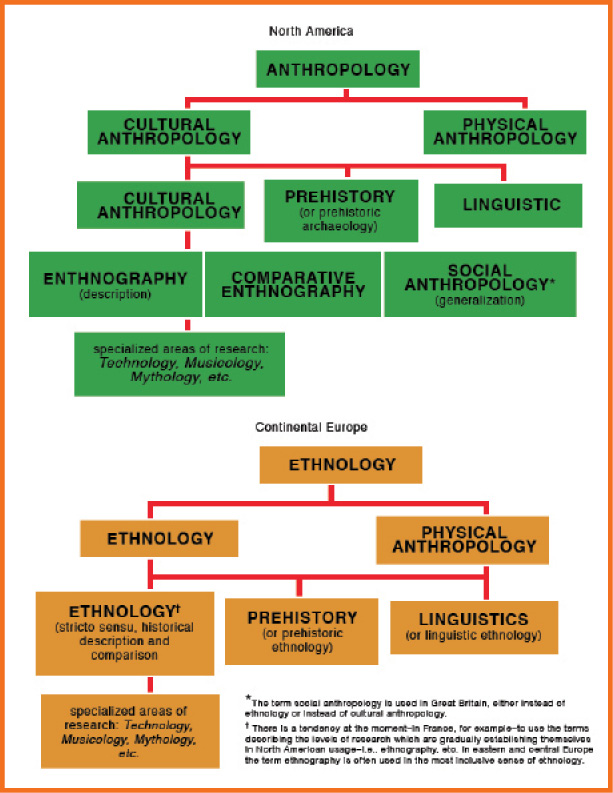

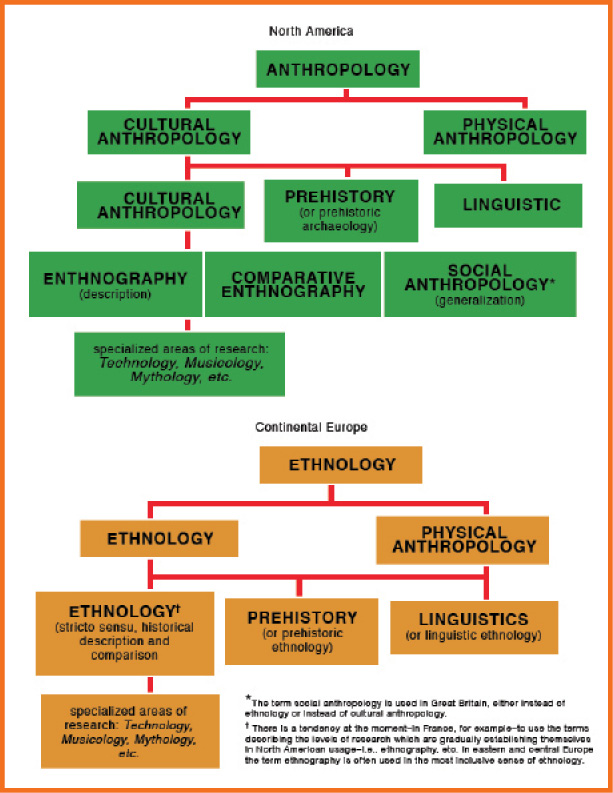

Different terms are used to describe the fields of anthropology in North America and Europe. While in North America the term anthropology is used to name the whole subject, in Europe the name ethnology is applied. What is called cultural anthropology in North America is also termed ethnology in European countries, except in Great Britain, where it is called social anthropology. The term physical anthropology is used in both parts of the world.

The three major subareas of cultural anthropology in North America are historical anthropology (or ethnology), prehistory (or prehistoric archaeology), and linguistics (or linguistic anthropology). In Europe the subareas are ethnology (in the strictest sense as the historical description and comparison of groups of humans), prehistory (or prehistoric ethnology), and linguistics (or linguistic ethnology).

The science of physical anthropology has focused to a great extent on determining the place of human beings in nature, on comparing them with lower primates, and on analyzing differences between humans and their human and nonhuman ancestors. The field was once concerned with classifying human beings into what were thought to be distinct types called races. In the late 20th century, however, studies of genetics and factors such as blood type indicated that the concept of race has no basis in biology. Instead, physical anthropologists today study the gradual variations of a given physical characteristic in human populations found over a geographic area or environment. In pursuing its goals, physical anthropology has used the sciences of comparative anatomy, evolution, genetics, and archaeology.

Terminology of anthropological disciplines in North America and continental Europe.

Modern physical anthropology began taking shape in the first half of the 19th century when there arose a great interest in studying the origins of humankind, the supposed biological relationships between the races, and the changeability of human beings as an animal species. In working out their theories, anthropologists devised a framework based on the ancient idea of a great chain of being. This was a model of nature that arranged all species in a hierarchical order, from the lowest to the highest. Anthropologists believed that the model would show a steady progression from lower life forms up through the lower primates (apes and monkeys) to human beings. Since no continuous progression to human beings could at first be found, scientists theorized that there must be a missing link between the lower primates and man.

In order to classify and distinguish between the apes, monkeys, and various races of man, anthropologists in the 19th and early 20th centuries used comparative anatomy, measuring brain size, cranial capacity, arm and leg length, and height. They also noted the color of skin and personality traits as clues for putting animals and the races in their proper order. Although these studies were presented as representing objective science, they really reflected social attitudes and constructs, not biology. Modern anthropology recognizes that such categorizing and ranking has no scientific validity.

The work of most 19th-century anthropologists was hampered by ignorance in a number of areas. The age of the Earth was unknown, for instance. Many people, in accordance with the religious teachings of the time, believed it to be about 6,000 years old. Religious teaching also suggested that all species were created at one time, thus precluding any evolution from lower to higher forms. The first archaeological discoveries indicating the very ancient origins of humankind were not made until the middle of the 19th century, and then many anthropologists ignored or disputed them. The first major breakthrough for anthropologists came in the natural sciences when in 1859 Charles Darwin published his On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

An anthropologist works at a farm outside of Montevideo, Uruguay.

Evolution was a crucial concept for anthropologists in reaching an understanding of the origins of humans. The idea of natural selection had huge implications for the study of anthropology, though many decades passed before they were fully appreciated. Darwin held that nature selects those forms that are better adapted to a particular geographic zone and way of life. The notion of adaptation implied that organisms changed slowly over millions of years. In the late 19th century, anthropologists recognized that the human species had an evolutionary history extending back several hundred thousand years, rather than just a few thousand as previously thought. The idea of adaptation also eliminated any need for a missing link, though this theory persisted well into the 20th century. The missing link had not been considered to be a product of evolutionary development but a creature placed between man and ape in the natural order of things.