All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

FIRESIDEand colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster,Inc.

Minden, Eliza Gaynor.

The ballet companion: a dancers guide to the technique, traditions, and joys of ballet / Eliza Gaynor Minden.

p. cm.

A Lark production.

A Fireside book.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Ballet dancingHandbooks, manual, etc. I. Title.

Introduction

When Anna Pavlova was a young dancer in Russia, she faced stiff competition from a bevy of imported hotshot Italian ballerinas. With their tricked-out shoes and their formidable technique they performed marvels on full pointe: endless balances, dazzling pirouettes, even an unheard-of thirty-two fouetts. Pavlova toiled to make herself into a virtuosa in their mold.

Fortunately her teacher Pavel Gerdt advised her to leave off the tricks and turns and focus on developing her own innate qualities: delicacy, lyricism, expressivity. In the end Pavlova triumphed as a Romantic dancer at a time when hard-boiled classicism was all the rage, and she went on to foment balletomania the world over. Of course, she never stopped working on her technique; she even got the greatest Italian ballet master of all, Enrico Cecchetti, to give private lessons to her and no one else. And she did adopt the newfangled Italian shoes (albeit doctored in her secret way), but not just for flash or bravura. Pavlova did the opposite: she used pointework to convey achingly beautiful vulnerability.

Pavlova became a legend by tapping into her genius for self-expression rather than by technique alone. She cultivated her own eloquent voice. And you can do the same even if you never set foot on a stage. Certainly executing steps well provides tremendous satisfaction. But ballets joy lies not just in doing steps; its in dancing themin the pleasure of expression through movement, of union with music, of singing with your body. I hope this book helps you not only in developing proficiency but also in discovering your voice.

The Ballet Companionoffers a discussion of technique that is not just how to, but why. You already know what tendus are because you do them in class. But you may not realize why you do so many, or that the meaning of the word in French (stretched) defines the quality of the movement, or that a famous choreographic passage, the opening of Balanchines Theme and Variations , is based on themor how by perfecting your tendu you can improve your technique overall. Throughout the book, I connect the work you do in class to the bigger picture.

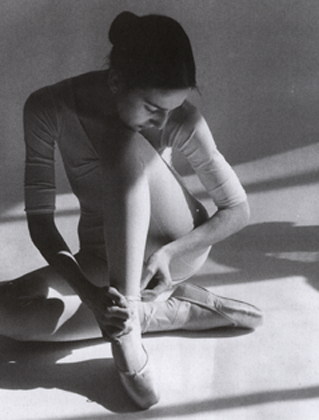

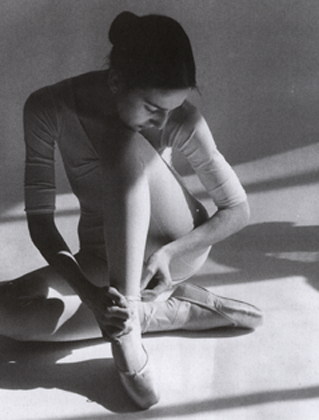

Eliza Gaynor Minden, age fifteen.

That picture, of course, includes performance. Looking as much as doing sparked my own love of ballet. My first impressions were formed watching Fonteyn and Nureyev, Baryshnikov, Fracci, Makarova in Swan Lake , Kirkland in Giselle , and the opening night (a school night at that) of Balanchines 1972 Stravinsky Festival with its landmark premieres. Granted, thats a hard act to follow, but every generation has its own superb dancers. Let todays inspire you.

In the back of this book you will find a collection of choreographic greatest hits along with some of my favorites that are less well known. Go to the ballet as often as you can. If you can see a work repeatedly, thats even better. A second or third viewing reveals the craftsmanship in the choreography and lets you compare different interpretations. In deciding what you admire and what you dont, what you allow to influence you and what you reject, you will shape your own character as a dancer.

Sometimes the first step toward finding your voice is to realize that its okay to have one. This book is generously sprinkled with nuggets of ballet history that show how often a distinctive choreographic or performing personality has influenced and enriched ballet. Things we take for granted todaythe one-act ballet, the tutu, the overhead lift, the blocked pointe shoe, even women dancing professionallyall were innovations in their time and sometimes bitterly resisted. Dance history is full of skirmishes between rebels and traditionalists, but ultimately dance embraces new voices and rewards those who take risks.

As a student I was captivated by ballet history and contrived to write every school term paper I could on a ballet subject. An assignment on great Americans became an essay on Ted Shawn, an art history project a study of Diaghilevs collaborations. My poor logic professor asked for an example of a well-constructed argument and got a scathing critique of the dance program at Yale. I took great pleasure in using my obsession with dance as a means of enlivening schoolwork; you might, too.

Ballet history is deliciousits rich and glamorous and fun. Its also important for your dancing in a serious way. You develop an informed artistry when you understand why the Sylph holds her arms differently from the Sugar Plum Fairy, or why a Bournonville allegro must bounce along the way it does. Petipa and Ivanovs Swan Lake and Fokines Dying Swan were choreographed only ten years apart and both feature swan-women in white, feathered tutus. But to dance Fokine like Petipa would be to miss the point. Fokine loathedamong other thingsclassicisms stale verticality and lack of expressivity, so his reforms included a liberation of the arms and upper body. This isnt a stylistic nicety; its a wholly different approach. We know about it from history: from his own manifesto and from the accounts of the dancers he trained.

I hope the historical tidbits in this book intrigue you enough so that you read more. Dancers autobiographies are often delightful and engrossing. Its fascinating to read about your own familiar exercises and routines as they were in other times: in Imperial Russia or with the Ballets Russes or under Communism or for Balanchine. Some of the dancers stories will surely resonate with you and contribute to the creation of your own dancing personality.

Ballet training rightly focuses on technique and artistry, but dancers are not indestructible, and they ignore their health at their peril. Ballet has become more overtly athletic. Although dancers still pretend not to sweat on stage, and still conceal their exertions under serene smiles, their bodies are being pushed and pulled as never before. Fortunately, there is now far more awareness and knowledge of dancers health.

A whole new field of medicine has sprung up, and its practitioners have much to offer on the subject of injury prevention and safe training. Eating disorders, once a shameful secret, are now brought into the sunlight for compassionate confrontation and cure. Cross training is widely recognized as a complement to class that can speed the process of building strength and flexibility. I have devoted an extensive section of this book to the healthy dancer.