The Cambridge Companion to Ballet

Ballet is a paradox: much loved but little studied. It is a beautiful fairy tale; detached from its origins and unrelated to the men and women who created it. Yet ballet has a history, little known and rarely presented. These great works have dark sides and moral ambiguities, not always nor immediately visible. The daring and challenging quality of ballet as well as its perceived safe nature is not only one of its fascinations but one of the intriguing questions to be explored in this Companion. The essays reveal the conception, intent and underlying meaning of ballets and re-create the historical reality in which they emerged. The reader will find new and unexpected aspects of ballet, its history and its aesthetics, the evolution of plot and narrative, new insights into the reality of training, the choice of costume and the transformation of an old art in a modern world.

The Cambridge Companion to

BALLET

EDITED BY

Marion Kant

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town,

Singapore, So Paulo, Delhi, Tokyo, Mexico City

Cambridge University Press

The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK

Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521539869

Cambridge University Press 2007

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 2007

A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-0-521-83221-2 Hardback

ISBN 978-0-521-53986-9 Paperback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Information regarding prices, travel timetables, and other factual information given in this work is correct at the time of first printing but Cambridge University Press does not guarantee the accuracy of such information thereafter.

Contents

Marion Kant

Jennifer Nevile

Marina Nordera

Barbara Ravelhofer

Mark Franko

Dorion Weickmann

Sandra Noll Hammond

Tim Blanning

Judith Chazin-Bennahum

Inge Baxmann

Sarah Davis Cordova

Anne Middleboe Christensen

Marian E. Smith

Lynn Garafola

Thrse Hurley

Lucia Ruprecht

Marion Kant

Erik Nslund

Tim Scholl

Matilde Butkas

Juliet Bellow

Jennifer Fisher

Zheng Yangwen

Lester Tome

Marion Kant

List of illustrations

Foreword

Ballet is a theatre art that, by virtue of its origins, is essentially and incontrovertibly European. Those origins are, in large measure, to be sought in the Italian courts of the Renaissance in the fifteenth century, where it developed as a means of displaying the splendour and power of the ruling prince. A century or so later it crossed the Alps in the marriage train, so to speak, of Catherine de Medici, the chosen bride of King Henri II of France, becoming a dominant feature in the entertainments of the French court for more than a century until well into the reign of Louis XIV. By that time professional dancers were already being employed to add variety and brilliance through a technique that far exceeded that of even the most talented of the courtiers. However, halfway through Louis XIVs reign the court ballet went into a sudden decline, not so much on account of the kings growing corpulence as through the increasing demands on his treasury of the wars in which France then became embroiled. Providentially a far more suitable and lasting future for the ballet was then provided by the king himself in creating the Acadmie de Musique, which was to be the forerunner of the institution now known as the Paris Opra. Here professional dancers found an arena from the very outset, and dance as spectacle was to play a conspicuous role in the creation of what we now recognise as the art of classical ballet. At first it took the form of an adjunct to opera, as in the opera-ballets of Rameau, but from the mid-eighteenth century it became an independent theatre art, in which the stage action was conveyed by the dancers themselves in pantomime. This was one of the great theatrical turning-points that marked the Age of the Enlightenment.

While Paris continued to be regarded as the prominent centre of this new art form, ballet soon took root elsewhere in Europe. Italy, where the infant art had been nurtured, became a fertile field as many opera houses throughout the peninsula adopted ballet as a respected adjunct to the opera. In Milan and Naples major ballets were being produced on the stages of those cities celebrated opera houses, based upon plots that required powerful gifts of pantomime in those players responsible for the dramatic roles. By the end of the eighteenth century ballet was generally recognised throughout Europe as a significant theatre art, and one with its own philosopher in the distinguished figure of Jean-Georges Noverre, whose Letters on Dancing are to this day still revered as a classic.

France retained its ascendancy notwithstanding the cataclysm of the Revolution, a period that saw the emergence of the formidable figure of Pierre Gardel, who was to dominate French ballet for some forty years. When the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars had receded into history, Paris was still regarded as the fountain-head of the theatrical dance, and it was there within the august walls of the Opra that the conflict between the opposing trends of classicism and romanticism in the art of ballet was finally and unequivocably resolved in the latters favour. Under the banner of romanticism the choreographers Taglioni and Perrot produced those two ballets that are treasured today as lasting classics, La Sylphide and Giselle. The Paris ballet continued to enjoy a dominance that would remain virtually unchallenged until the last decades of the nineteenth century, when the world became increasingly aware that ballet had taken root in most fertile soil in St Petersburg, underwritten by the vast wealth of the tsars but preserving nevertheless a vital French connection in the person of the Marseilles-born ballet master Marius Petipa.

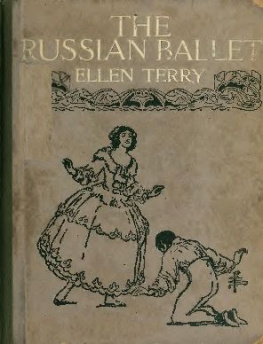

In the early 1900s the first rumblings were felt of the revolution that was to come, and it was in the last few years before the outbreak of the First World War that Europe was given its first taste of the balletic riches that Russia had to offer. This came about through a privately sponsored company of dancers from the Imperial Theatres organised and directed by Serge Diaghilev that conquered Paris literally overnight in the summer of 1909, presenting not extracts from the works of Petipa, but a programme mainly produced by a younger choreographer, Mikhail Fokine. This extraordinary enterprise was continued, with a break of a few years resulting from the war, until 1929 when Diaghilev died. The consequences of his demise was to prove the permanence of the legacy left by that extraordinary company in the course of just two decades an eye-blink in the context of history for the disappearance of its guiding spirit let loose a younger brood of choreographers notably Nijinska, Massine, Balanchine and Lifar to propagate a new vision of ballet throughout Europe and America.

Next page