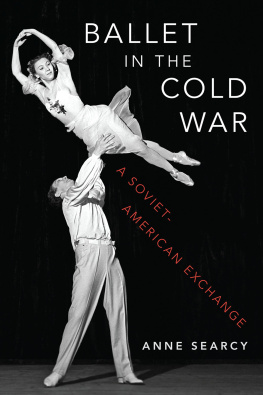

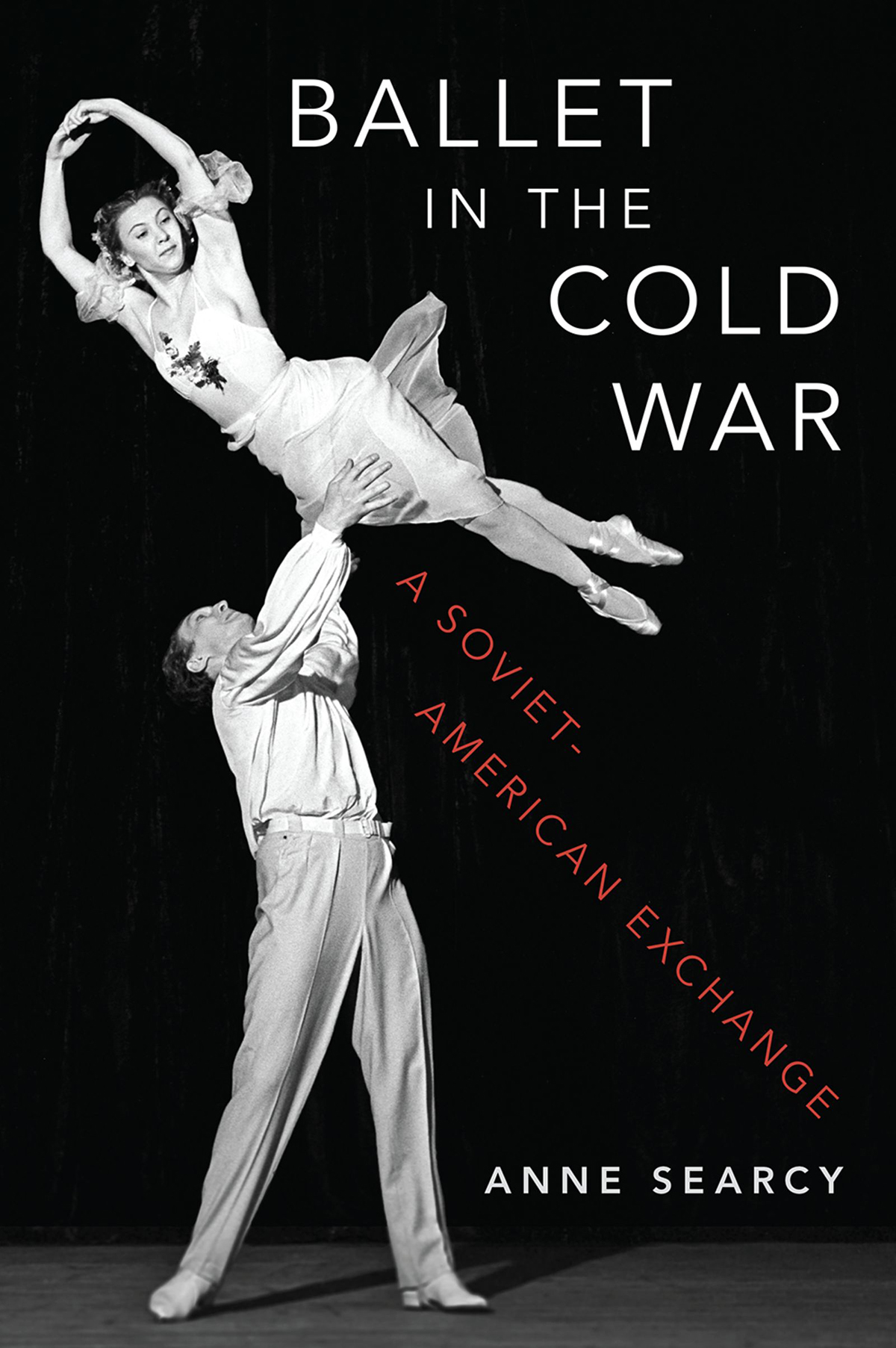

Ballet in the Cold War

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Searcy, Anne, author.

Title: Ballet in the Cold War : a Soviet-American exchange / Anne Searcy.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2020] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020008342 (print) | LCCN 2020008343 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190945107 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190945121 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: BalletPolitical aspectsUnited States. |

BalletPolitical aspectsSoviet Union. |

United StatesRelationsSoviet Union. | Soviet Union

RelationsUnited States. | Cold War.

Classification: LCC GV1588.45 .S43 2019 (print) |

LCC GV1588.45 (ebook) | DDC 792.8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020008342

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020008343

Publication of this book is supported in part by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, supported in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

For Frederick

Contents

I am enormously grateful to the many people who have helped me as I researched, wrote, and revised this book, first of all to the artists and audience members who allowed me to interview them for this project: Marina Kondratieva, Michael Colgrass, and Judith P. Zinsser.

The book would not have been possible without my time as a fellow at the Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University, generously also sponsored by the Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia. I am grateful to the institution itself and to the support there from Jennifer Homans, Andrea Salvatore, Nancy Sherman, Amanda Vaill, and the other fellows. In addition, I conducted the research for this project with help from a Richard F. French prize from the Harvard Music Department, an Abby and George ONeill Graduate Research Travel Grant from the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, and an Alvin H. Johnson AMS 50 Dissertation Fellowship from the American Musicological Society.

I am enormously grateful to my editor, Norm Hirschy, for his encouragement, belief, and insightful recommendations on how to shape the book, as well as his ability to answer dozens of emails seemingly before I had hit send.

Many archivists helped me in locating sources for this project, including Dmitri Viktorovich Neustroev and Irina Nikolayevna Kalugina at the Russian State Archive for Literature and Art and Vera Ekechukwu and Geoffrey Stark at the University of Arkansas Libraries, as well as the archivists at the Museum of the Bolshoi Theater, the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History, the State Archive of the Russian Federation, the Houghton Library, and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. I am also grateful to Robert Greskovic and Wenshuo Zhang for allowing me access to their personal archival collections. I thank the Jerome Robbins Rights Trust for allowing me to access the Jerome Robbins papers, and the George Balanchine Trust for granting me permission to use images of his choreography in this book.

As I prepared for my research, I received advice and logistical support from Robyn Angley, Stephanie Plant, Hugh Truslow, Jill Johnson, and the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. I also am thankful for the many years of support from librarians including Liza Vick, Kerry Masteller, Andrew Wilson, Nancy Zavac, Amy Strickland, and Joy Doan. I received invaluable assistance as well over the years from Nancy Shafman, Eva Kim, Karen Rynne, Kaye Denny, Charles Stillman, and Dianne Gross. My colleagues at the Frost School of Music, including Marysol Quevedo, Melvin Butler, Brent Swanson, and David Ake, have also encouraged me in my research. I am also grateful for the support of my colleagues at the University of Washington.

I am profoundly thankful for the many years of support, encouragement, and mentoring from both of my advisors, Carol Oja and Anne Shreffler. I am also deeply grateful to Kevin Bartig, who was always willing to look at chapters and provide encouragement as I made my way into the field. I am also thankful to Danielle Fosler-Lussier for her insights on Cold War music and politics. In addition, many colleagues, mentors, and friends have given feedback on my drafts over the years, including Julie Buckler, Katie Callam, Elizabeth Titrington Craft, Hayley Fenn, Joseph Fort, John Gabriel, Joshua Gailey, Aaron Hatley, Monica Hershberger, Hannah Lewis, Emily MacGregor, Lucille Mok, Matthew Mugmon, William OHara, Samuel Parler, Frederick Reece, Caitlin Schmid, James Steichen, Michael Uy, and Micah Wittmer. Olga Panteleeva gave invaluable help in checking some of my translations.

I am profoundly grateful for my friend Nora Nussbaum, who has been unflagging in her support, always just a phone call, email, or train ride away. It is truly impossible to thank my parents enough. Margaret Searcy and William Searcy have loved and encouraged me all my life. I also want to thank my family, Christopher Searcy, Michelle Afkhami, Elizabeth Afkhami Searcy, Kathryn Afkhami Searcy, Anna Reece, and Graham Reece. Without them, none of this would be possible. Last, and most of all, I thank Frederick Reece. He has been with me through every draft. He has listened to all my worries and celebrated all my good fortune. I dedicate this book to him.

I have used the Library of Congress transliteration system for Russian in bibliographic citations. In the text itself, I have suppressed all soft signs and changed -ii to -y and -aia to -aya at the ends of family names. I have also made exceptions in the cases of figures who are well known in the United States under alternate transliterations, relying on the spelling of their names in English-language programs from 1959 and 1962. For example, I use Tchaikovsky instead of Chaikovsky and Maximova instead of Maksimova.

Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own.

Ballet in the Cold War

Madison Square Garden, New York City, May 1959

A slender woman charges diagonally across the stage. As she reaches the center, she leaps to the side, arms flung out in front, feet pointed behind her. An audience of thirteen thousand people, some sitting so far away that the woman looks like nothing but a tiny dot, gasp as she flings herself into the unknown. There is a moment of anxiety as she hangs suspended. Then her muscular partner catches her in his outstretched arms, and the viewers erupt into screams and cheers.