I have received help and advice from many people in the writing of this book. Dancers, musicians, critics, historians, staff and friends were generous in answering my questions, making suggestions and passing on their memories.

My first thanks are to the people who worked in or with the Company: Lionel Alberts, John Bakewell, Monica Beck, Joan Benesh, Deborah Bull, Lesley Collier, Jonathan Cope, Anthony Dowell, David Drew, Julia Farron Rodrigues, Beryl Grey, Jeanetta Laurence, Brenda Last, Thomas Lynch, Donald MacLeary, Deborah MacMillan, Monica Mason, Pamela May, Merle Park, Georgina Parkinson, Vanessa Palmer, Helen and David Quennell, Genesia Rosato, Anthony Russell-Roberts, Lynn Seymour, Antoinette Sibley, John Tooley, David Wall and Peter Wright.

At the Royal Opera House, Janine Limberg was tireless in arranging and suggesting interviews. I would also like to thank Simon Magill, Anne Bulford, Katie Town and Georgie Perrott.

I would like to record my gratitude to the staff of the Royal Ballet Archives, particularly Francesca Franchi, Julia Creed, Rachel Hayes and Tom Tansey. I also wish to thank the librarians and archivists of the Theatre Museum, Laban and the Royal Academy of Dance. Jane Pritchard, of the Rambert Archives and the Theatre Museum, was exceptionally generous in giving me access to her own archive, and in reading and correcting some of the manuscript. Jon Gray, at the Theatre Museum and at TheDancing Times, advised on sources and photographs, correcting the final proof with great care and kindness. Clement Crisp made invaluable suggestions. Gail Monahan and Meredith Daneman read portions of the manuscript, making essential comments.

I would like to thank Gavin, Maggie and Leo Anderson, Patricia Daly, Sarah Frater, Robert Gottlieb, Robert Greskovic, Clare Jackson, Laurie Lewis, Claire Lindsay, Barbara Newman, Jann Parry, Joan Seaman, David Vaughan and Sarah Woodcock for all their help and support.

I wish to thank my agent, Michael Alcock, and my editor, Belinda Matthews. At Faber and Faber, I would also like to thank Elizabeth Tyerman and Kate Ward.

Finally, I thank Mary Clarke and Alastair Macaulay, both critics, historians and friends. Mary Clarke, editor of The Dancing Times and author of the invaluable history of the Companys first twenty-five years, made vital introductions, suggestions and criticisms, and permitted me to consult and quote her correspondence. Alastair Macaulay, most generous and scrupulous of readers, took infinite care in reading, correcting and commenting on the manuscript. He also allowed me to consult the proceedings of the RAD Fonteyn conference ahead of publication, and lent me enough rare books and recordings to fill two taxis. This book is dedicated to both of them with gratitude and love.

Preparation

192631

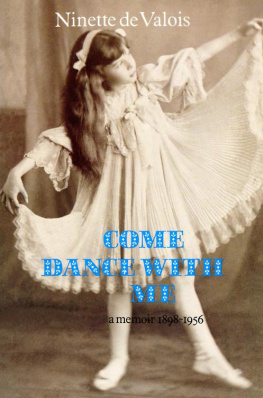

PREVIOUS PAGE Ninette de Valois, founder of The Royal Ballet, in 1949: Gordon Anthony Collection, The Theatre Museum, V&A Images

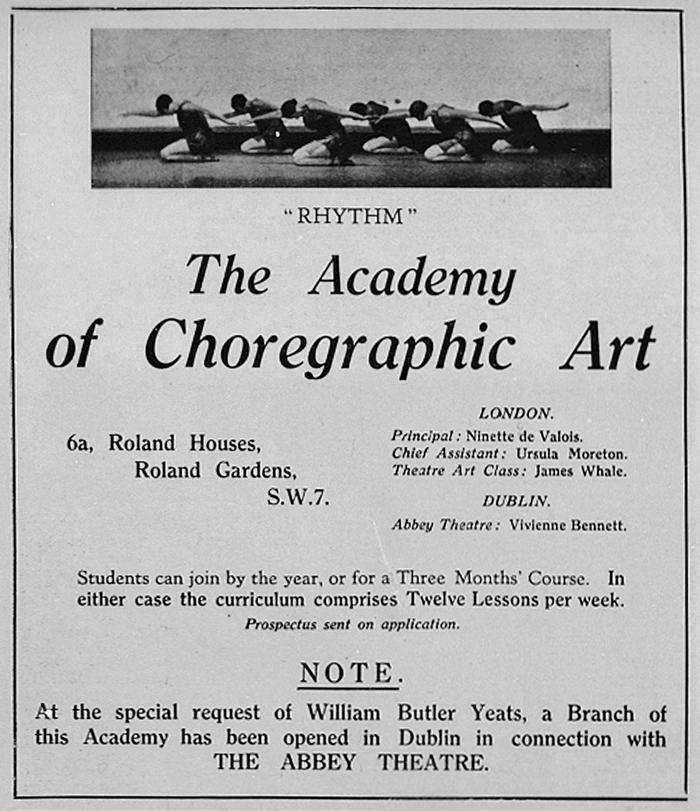

ABOVE The Academy of Choreographic Art, advertisement from the Dancing Times: by courtesy of Dancing Times, January 1928

The Royal Ballets seventy-fifth anniversary falls on 5 May 2006. The Company hasnt always counted its birthdays correctly: its founder, Ninette de Valois, once held a coming-of-age celebration in the wrong year. What cant be miscounted is how much de Valois achieved, how quickly. She built a company from scratch, taking it to world-conquering fame in less than two decades. Her methods have shaped not just British ballet but companies across the world: directly, through the troupes founded or led by Royal Ballet dancers, and indirectly through the image of the Company.

From very early on, The Royal Ballet was a repertory ballet company. It took works from the past, from other traditions, while creating its own new choreography. De Valoiss model helped to shape ballet in the twentieth century and beyond. She and her successors created a repertory that is one of the richest in the world, including classic stagings of ballets from the nineteenth century and the Diaghilev era. Frederick Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan were the Companys own defining choreographers, spending most of their creative lives with The Royal Ballet. Dancing these works, the Company developed its own distinctive accent, with clear musicality and a strong sense of drama.

Maintaining a tradition can be as hard as founding it. The Royal Ballets toughest moments have come in the last twenty-five years. Its standards and identity have been threatened. This history concerns survival as well as growth, decline and recovery as well as influence. It was written at a time of optimism and excitement. Under Monica Mason, the Company has been rediscovering a neglected past; as I wrote, ballets I had been researching were brought back to the theatre. A new generation of dancers has responded to their challenges of technique, style and authority.

*

Ninette de Valois was a formidable, charming and contradictory woman: far-sighted, ruthless and selfless. She was a disciplinarian who adored rebels, an Irishwoman who founded a pillar of the British establishment. She built a highly organised system, and she loved upsetting apple carts. After visiting Russia, she came straight back to her own school and taught her teachers new steps and methods, re-examining her own basic principles. She was always ready to change her mind.

Her company and her school had several name changes before settling down as The Royal Ballet, but de Valois never put her own name above the title. It is the belief of the present Director, she said sternly in 1932, that if the ballet at Sadlers Wells does not survive many a Director, then it will have failed utterly in the eyes of the first dancer to hold that post.

She was superbly pragmatic. John Tooley, who worked with her at Covent Garden from the 1950s, remembers how clearly she would set out her plans, all leading firmly in a chosen direction. Then something would happen which caused her to deviate. She would say, I cant miss that opportunity. I know its not quite in the direction we talked about, but its taking us forward. She was so much like that. Throughout her career, de Valois would turn her chances to account. Circumstances thrust a lot on you, she wrote serenely, and when they arise you simply meet their demands.

At first, de Valois was the ballerina of her own company, but she regularly put herself second cast after visiting dancers. Having In 1959, she planned one last ballet, The Lady of Shalott, to music by Arthur Bliss. It never happened. She decided that Kenneth MacMillan, already singled out as The Royal Ballets next major choreographer, should do a new ballet that season, and handed over her own rehearsal time.

Plenty of dancers and teachers were terrified of her. Monica Mason remembers de Valoiss visits to The Royal Ballet School in the late 1950s. The whole atmosphere was rather like nurses and matrons used to be when the surgeon was coming round everybody was spruced up and on their best behaviour, on their mettle People seemed scared to death. In rehearsals, de Valois could be hasty, impatient, furious. Her rages were quick, and quickly over. She wouldnt let you gloat over it, said Pamela May, who remembered the storms of her classes. During the war, de Valois was nicknamed Madam; she cheerfully accepted the name, and would sign letters to members of the Company with it.