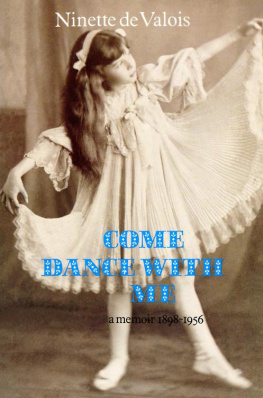

I T IS a very real delight for me to reflect on the fact that Dublin has come forward to republish this book. So much of the early part is devoted to memories of a very happy childhood in the midst of the famous and lovely Wicklow hills, with its Wicklow weather, foxhunts and vivid recollection of a real Irish village.

The execution of an Irish jig at a childrens party really set things going. The performance was a demand on my part as I did not approve of the skirt dance executed by another young guest. I am afraid that I was right. My jig was authentic, the work of an Irish countryman bent on me executing it in an Irish farmhouse kitchen. It started my life of dancing and was definitely my first stage performance. The childrens party was held at the de Robecks country housemy host simply said to my mother when I had finished: Train her. I draw attention to this aspect of the book to show the early influence of Ireland in the original inspiration offered me by that jig.

May another generation honour me by reading and enjoying this new edition, and once more I express my happiness that it is Dublin who wants me to dance again through its pages.

M ANY friends suggested that I should take four months leave of absence to write this book. That would have been very pleasant; the book, though, would never have been written. It has been said that I am an indefatigable collector of discomfort and difficulty; certainly my mind prefers adversity and complexity to any state of smooth living. Thus, time and again, the throb and upheaval of my travels by every form of locomotion on land, sea and in the air, has been for me the perfect background music.

I would emphasise that these writings are, in effect, just an attempt to tell a story. The story, however, is not concerned with somebodys private life: it is just a glimpse of the private side of someones public life.

The manuscript has travelled far and wide when in the making. It has taken shape in trains, planes and boatson journeys stretching as far afield as Moscow and the Middle West of the United States. It has developed during quiet week-ends in the country; it has unravelled itself on a French cargo boat, when holidaying off the coast of North Africa. It has made staccato progress on non-pressurized aeroplanes over Eastern Europe, going to and from Moscow. At times it has made quite rapid progress on a 12,000-mile lecture tour of Canada and the United States, though it experienced neglect on the Observation Car of an American Zephyr train, with the surrounding country embraced by an awe-inspiring sunset. The neglect was heightened by the vision of a seemingly long silver cobra, winding its way ahead of the observation carthen the sudden intriguing realization that we ourselves were being towed by the silver cobra abruptly the daylight faded, and under the glow of electric light the manuscript once more came into its own.

I am going to miss my companion of the last fifteen months shared adventures, for a manuscript, I have discovered, is the ideal friendsilent and accommodating. It remains unresentful when mislaid, or when it is overworked by an attack of zeal and spare time on the part of the writer. It will stay submissive when erased, corrected and blue-pencilled to pieces. It exudes passive friendliness when you discard it after midnight, with a glow of content concerning your thoughts just expressed on its white surface. It turns the other cheek next morning, when, on re-reading your literary carryings-on of the night before, you are aghast: you forthwith erase rudely and scratch hysterically at the surface of your patient friendand who knows if its passivity might not reflect the fact that it could have told you all this last night?

The manuscript is, above all, your kindest editorfor it does not condemn or argue: silently it shows you the insufferable depths of your grammatical errorscrashing clichs and befogged thinking.

I am going to miss exercising my mind with the vivid business of remembering things forgottendelving backwards into time towards some incident glowing clearly, in a lost world that has made the correct year, day and date of the picture under survey of secondary importance. Such research spells tedium, and, as always, the amateur loses patience over matters that are concerned with dry precise reckoning.

Working over the last fifteen months, with the mental machine in full swing, I realize that I must always have wanted to have the companionship of a manuscript: for I recollect that there is one day in every week of my childhood that stands out with a persistent clarity of memoryI can still recall that it was on Wednesday that my governess demanded the writing of the schoolroom weekly essay. I also recollect that Tuesday was devoted to considerable anxiety on my partfor would she give me a subject next day that I would consider interesting? Would grown-ups never, never let me choose my own subjects?

During these present writings, something has emerged in the form of a sobering truth: I am convinced that we shape no event as forcibly as events shape us.

To pen an autobiography is to force to the front of your powers of observation the startling proof of your own lack of any real capacity to plan life. We are all aware of living life to the full on specific occasionsand with intense deliberation. If, though, these occasions are carefully scrutinized, it becomes clear that no carefully arranged basic plan brought them about: it is nearer the truth to admit that, at such times, we submit to the event, whose future shape and significance is unknown to us

How many deep impressions we receive that bear no relation to the aims that we set out to achieve: the journey is taken for some particular objective, but it is not necessarily the fulfilment of the objective that stays with us through timethis is often quickly forgotten, and often changed by circumstances so as to be beyond recognition. What stays with us are sights, sounds, friendships, books, pictures; the meal eaten that owes its distinction to the surrounding landscape, or a curious turn of phrase in conversation; the memory of a new land seen at sunrise and at sunset remains with us when the lifes purpose on that day has completely faded.

We carry within ourselves a curious medley of matter. We are unconscious hoarders: the range of the store is varied, the choice unrestrained, the result strangely intimateunconcerned with our surroundings and their inhabitants. These inner realities cannot be shared with others, not even those dear to us. We hoard to nourish and sustain our individual solitude: that business of being alone, as we always must be, even in the largest of crowds. No one can elude his personal solitude (although he may waste it and ignore its importance). To elude it, however, would be to lose oneself, for to move away from the inner sense of reality is to develop a sicknessto become unaware of the meaning of ones individual entity in the whole.

Such experiences are perceived and understood quite differently by each one. Art and the artist succeed when they show us anew things that we know already; when they conjure up a vision that sows a seed to be reborn, in some other form, within ourselves.

It would seem that nothing belongs to any of us exclusively; everything is for all to see and interpret in a million different ways, and the sum total is life, in its infinite variety of individual living.

What does it feel like to be old? said the boy.