ALSO BYMary Taylor Simeti

Pomp and Sustenance:

Twenty-five Centuries of Sicilian Food

Bitter Almonds:

Recollections and Recipes from a Sicilian Girlhood

(with Maria Grammatico)

ACCLAIM FOR Mary Taylor Simetis

On Persephones Island

Fascinating. From the delicate steps in wine-making to the Virgin Marys joyous meeting with the risen Christ in the Easter morning procession at Castelvetrano [this is] much more than a daily record of happenings, and Simeti is much, much more than an eager American junketing around with pen and wonder at the ready.

The New York Times Book Review

In telling her story she reflects upon the history, myths and legends that have filtered into the traditions of Sicily and upon the islands problems and pleasures. We see all these with freshness and amazement. Simeti has done a rare thing: she has written a happy book about Sicily and yet there is an undercurrent of sadness, one true to the reality of the island.

Washington Post

Simeti displays a deft touch with scenic description and an amiably unsentimental view of country neighbors who are as wily as they are picturesque. Overall, she describes a beautiful country in which past and present collide rather than merge, and where families like her own live fairly comfortably in what amounts to a war zone.

The Atlantic

Other erudite writers have written of these aspects of the Sicilian past, but rarely with the authors talent for firmly engaging the readers attention. Entrancing.

Philadelphia Inquirer

A joyous, sensory celebration of an island and a people pulsating with life.

American Way

Mary Taylor Simeti

On Persephones Island

Mary Taylor Simeti was born and brought up in New York City. In 1962 she went to Sicily, where she married and raised two children. She is also the author of Pomp and Sustenance: Twenty-five Centuries of Sicilian Food and, with Maria Grammatico, Bitter Almonds: Recollections and Recipes from a Sicilian Girlhood.

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, OCTOBER 1995

Copyright 1986 by Mary Taylor Simeti

Drawings copyright1986 by Maria Vica Costarelli

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1986.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: Penguin Books Ltd. Exerpt from The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, translated by Rex Warner (Penguin Classics, 1954).

Copyright Rex Warner, 1954. Reprinted by permission of Penguin Books Ltd., London. Sellerio Editore. Excerpt from Delle cose di Sicilia, Vol. I, edited by Leonardo Sciascia. Sellerio Editore, Palermo, 1980.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Simeti, Mary Taylor.

On Persephones island.

p.

1. SicilySocial life and customs.

2. Simeti, Mary TaylorHomes and hauntsItaly

sicily. I. Title.

DG865.6.857 1986 945.8092 85-45599

eISBN: 978-0-307-77311-1

v3.1

For Tonino

Contents

Scatter, now, some glory on this island, which the lord of Olympus,

Zeus, gave Persephone and bowed his head to assent, the pride of the blossoming earth,

Sicily, the rich, to control under towering cities opulent;

Kronion granted her also

a people in love with brazen warfare,

horsemen; a people garlanded over and again with the golden leaves of olive

Olympian.

Pindar, First Nemean Ode

PrologueOctober 1962

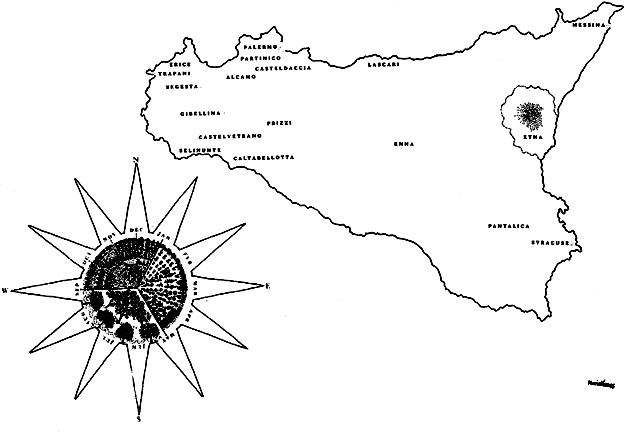

Like most young Americans traveling abroad in the early sixties, I arrived in Sicily with an excessive number of suitcases, considerable ignorance, and a great many warnings. In college I had studied the Sicilian Middle Ages, and over the summer I had read about Sicilian poverty in the writings of Danilo Dolci, the social reformer at whose center for community development I hoped to volunteer. This kernel of fact, meager as it was, had been fleshed out by the cautionary tales of friends and acquaintances, both at home and in the north of Italy, who all considered me courageous, if not downright foolish, to set off by myself for an island of dazzling sun and bright colors where bandits and mafiosi lurked in the shadows and where the rest of the population was proud and reserved, distrustful of foreigners, and sure to misinterpret the presence of a young girl alone.

Like most young Americans traveling abroad in the early sixties, I arrived in Sicily with an excessive number of suitcases, considerable ignorance, and a great many warnings. In college I had studied the Sicilian Middle Ages, and over the summer I had read about Sicilian poverty in the writings of Danilo Dolci, the social reformer at whose center for community development I hoped to volunteer. This kernel of fact, meager as it was, had been fleshed out by the cautionary tales of friends and acquaintances, both at home and in the north of Italy, who all considered me courageous, if not downright foolish, to set off by myself for an island of dazzling sun and bright colors where bandits and mafiosi lurked in the shadows and where the rest of the population was proud and reserved, distrustful of foreigners, and sure to misinterpret the presence of a young girl alone.

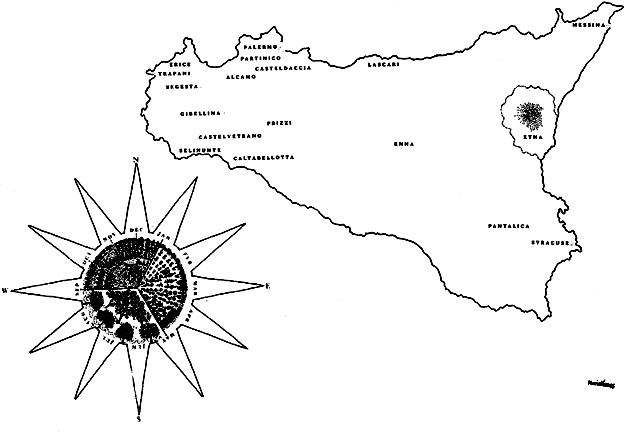

But from the window of the train that was bearing me south to Palermo the only color to be seen was gray: gray storm clouds piled up against gray mountains, gray olive trees tossing up the silver undersides of their leaves to the wind, and a gray sea tossing up silver foam onto gray rocks and beaches as the train threaded its way through the necklace of tunnels and coves strung out along the coasts of Calabria and northern Sicily.

My mother was living in Florence at that time, and it was there that I boarded the train in the middle of the night. Living on my own in a Sicilian village was not what my mother had had in mind when she offered me a year in Italy to celebrate my graduation from Radcliffe, and as she saw me into my compartment she was obviously hard put to be both encouraging and liberal minded, and yet with the same breath remind me to be careful about the men, the Mafia, the drinking water, and all the other things that would no doubt come back to her as soon as the train pulled out of the station.

On her graduation trip in 1924 she and her college roommate had left the boat at Naples and taken a train across southern Italy to Bari. They were the only women on the train, and the soldiers who shared their compartment spent the whole trip comparing my mothers ankles to those of her friend by measuring them between thumb and forefinger. Yet I did not recognize in her story my own age, my own curiosity, my own train ride south, since I was still too young to believe that she might ever have had any experience relevant to mine. So I hushed her up and settled my suitcases as quickly as I could, anxious not to disturb my fellow travelers who were already sleeping in their bunks. The Florence stop was not a long one, and soon we were moving, my mother waving forlornly in the yellow light of the station platform as the darkness swallowed us up.

It was not a restful night. I was too excited to do more than doze, and two of my fellow travelers turned out to be under three and equally excited, so I was glad when the train pulled into Naples in the uncertain light of a gray dawn, and I could abandon any pretense of sleep and introduce myself to the Sicilian family whose compartment I was sharing. My Italian was only just adequate and I was quite unaccustomed to the Sicilian accent, but I managed to understand that they had emigrated to Milan in search of work some years before and were returning to Palermo for a visit. I also managed to explain that I was traveling alone, via Palermo, to the town of Partinico, where I intended to live by myself and to work for the next year or two.

Like most young Americans traveling abroad in the early sixties, I arrived in Sicily with an excessive number of suitcases, considerable ignorance, and a great many warnings. In college I had studied the Sicilian Middle Ages, and over the summer I had read about Sicilian poverty in the writings of Danilo Dolci, the social reformer at whose center for community development I hoped to volunteer. This kernel of fact, meager as it was, had been fleshed out by the cautionary tales of friends and acquaintances, both at home and in the north of Italy, who all considered me courageous, if not downright foolish, to set off by myself for an island of dazzling sun and bright colors where bandits and mafiosi lurked in the shadows and where the rest of the population was proud and reserved, distrustful of foreigners, and sure to misinterpret the presence of a young girl alone.

Like most young Americans traveling abroad in the early sixties, I arrived in Sicily with an excessive number of suitcases, considerable ignorance, and a great many warnings. In college I had studied the Sicilian Middle Ages, and over the summer I had read about Sicilian poverty in the writings of Danilo Dolci, the social reformer at whose center for community development I hoped to volunteer. This kernel of fact, meager as it was, had been fleshed out by the cautionary tales of friends and acquaintances, both at home and in the north of Italy, who all considered me courageous, if not downright foolish, to set off by myself for an island of dazzling sun and bright colors where bandits and mafiosi lurked in the shadows and where the rest of the population was proud and reserved, distrustful of foreigners, and sure to misinterpret the presence of a young girl alone.