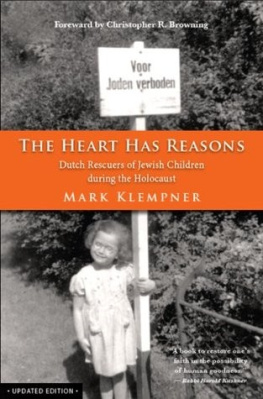

The heart has reasons that reason knows not of.

AUTHORS NOTE ON THIS UPDATED EDITION

Since the original publication of this book, I have continued to talk with and think about the rescuers and have incorporated some additional information and insights into this updated edition. I have also sharpened, tightened, and in some cases, improved the text. Several astute Dutch readers have pointed out minor errors, which I have corrected. Finally, I have updated the epilogue, and added twelve new photographs.

FOREWORD

The holocaust has become universally recognized as the ultimate measure of radical evil. It confronts those who study it with the insurmountable task of trying to explain the existence of harm-doing on an unimaginable scale, and above all, the motivation and nature of the perpetrators. But if the Holocaust is a story with all too many perpetrators and victims and all too few heroes, the goodness of the rescuers is as difficult to explain as the evil of the perpetrators.

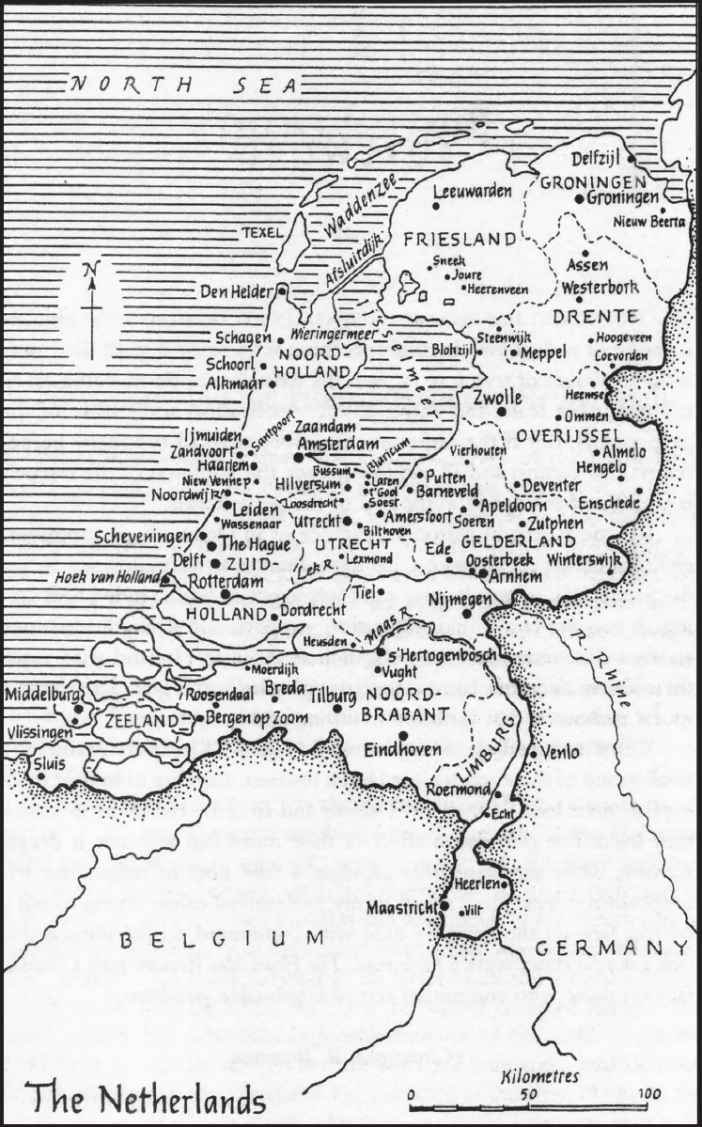

Rescue as part of national resistance, as in Denmark, or communal civil disobedience, as in Le Chambon, France, at least allows us to see the production of goodness as a group project, in which individuals acting in concert could find inspiration, support, and strength from one another. The individual rescuers, such as those in Holland who made their lonely decisions to risk everything to help strangers, acted with a moral autonomy that is both astonishing and humbling.

Without hyperbole or hagiographic fanfare, Klempner examines a small group of these remarkable Dutch rescuers, allowing us to hear them explain their lives in their own words and to sense the ethos in which they lived. The cumulative effect of their individual accounts is deeply moving, while simultaneously avoiding a false note of redemptive triumphalism. I have spent much of my professional career trying to put a human face on the ordinary men who committed acts of unspeakable evil. Like no other work I have read, The Heart Has Reasons puts a human face on those who committed acts of inestimable goodness.

Christopher R. Browning

BEGINNINGS

We need to know people whohave made choices that we can make, too,to turn us into human beings.

Richard Bach

This book is about ten dutch men and women who helped save the lives of thousands of Jewish children during the Nazi occupation of their country. But this chapter is chiefly about how I came to record their stories, and what those stories have meant to me personally. The importance of any rescuers testimony as a historical document speaks for itself. But my interest in these particular accounts is not only historical butunabashedlyinspirational. As the son of an immigrant who narrowly escaped the Holocaust, I found that these narratives helped me come to terms with my familys past; as an American trying to navigate the challenges of our times, theyve helped me to find my ethical bearings. In short, working with these people, recording their experiences, and getting to know them over the past ten years has changed my life. I hope that their example may do the same for others.

Fifteen years ago, I was a Los Angeleno with fraying nerves and a rapidly plummeting attitude. As I drove around the congested city, I wondered what had gone wrong. How had we, citizens of the most prosperous nation in the world, become so mistrustful, so incapable of caring about one another? Even the best of my fellow Los Angelenos seemed to be living in fear, on edgethe wealthy in Beverly Hills sequestered on gated estates with surveillance cameras and grounds security; the poor in East L.A. making do with deadbolts, chains, and barred windows.

Though I was doing all right as a musician, the self-aggrandizing nature of the music business was getting to me. All the individual acts of selfishness I had witnessed began to blur together, leaving me vulnerable to becoming another burned-out L.A. cynic. I suspected that if I spent another decade in the industry, I might turn into someone I didnt recognize, someone I wouldnt have wanted to know when I was younger.

I had come of age in the early 1970s, and like many young people at that time, believed youre either part of the solution, or part of the problem. In October 1969, my father, recognizing an unjust war when he saw one, announced to the family that he was going to join the upcoming march on Washington. My sister and I, though barely into our teens, convinced him to let us come along. Upon our arrival at the national mall, he hoisted me onto his shoulders, and I surveyed the seemingly endless multitude united in their opposition to the Vietnam War. It was at that moment that I first became moved by the spirit of activism, the power of the people to effect social change.