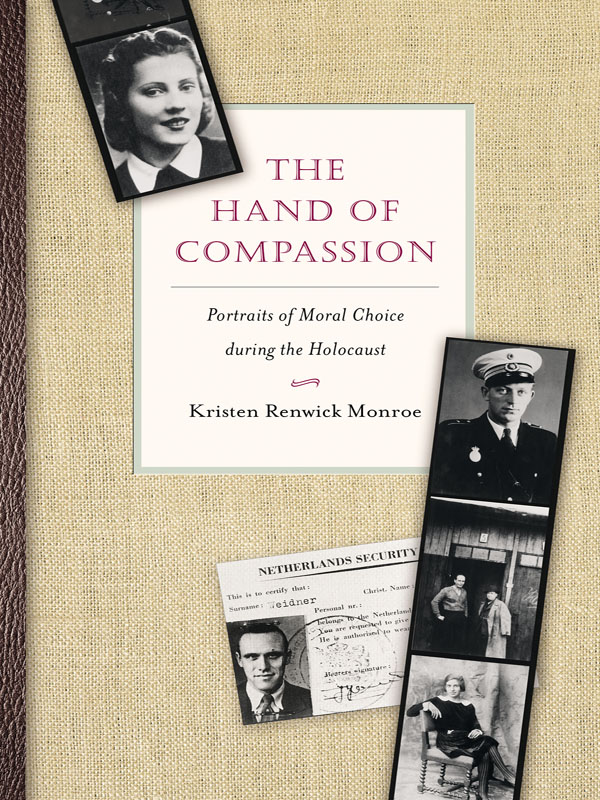

Copyright 2004 by Kristen Renwick Monroe

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press.

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Monroe, Kristen R., 1946

The hand of compassion : portraits of moral choice during the Holocaust / Kristen Renwick Monroe.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-691-11863-9 (cl : alk. paper)

1. Righteous Gentiles in the Holocaust. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)Moral and ethical aspects. 3. AltruismSocial aspects. I. Title.

D804 65.M66 2004

172.1dc22 2004044251

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Galliard.

Printed on acid-free paper.

pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

PREFACE

_____________________

THIS IS A BOOK ABOUT LOSS. It is a book about love. It is a book about normal, human decency transformed into extraordinary courage by a political regime so evil it confounds human comprehension. It returns us to those secret, frightening places in our own souls, places we seldom enter, touching only elliptically, late at night and alone, when a loved one has died or we are forced to face the eternal, when we cannot escape asking who we are, what we live for, and whether there is any sense in a world in which life and love and all we hold dear are so fragile.

This is a book about moral choice during the Holocaust, and it suggests the tremendous power of identity

This book grew out of my earlier work on altruism. The Heart of Altruism asked what caused altruism and then discussed the implications of this analysis for social and political theory. I found the critical impetus for altruism was psychological, a particular cognitive worldviewI called this the altruistic perspectivein which the actor saw himself or herself at one with all humanity. The importance of this worldview as an influence on behavior suggested the value of further research to sharpen understanding of the psychological process by which our sense of ourselves in relation to others both inhibits and shapes political activity.

The present volume addresses this challenge, moving beyond the identification of the altruistic perspective as a general phenomenon and attempting a fuller depiction of this perspective and its role in the moral psychology. It also expands my earlier theoretical analysis by treating altruism as a lens that can shed light onto moral theory.

Traditional moral theory often begins from first principles, making assumptions about the structure of agency and character; theorists then explain what motivates actors and how peoples practical moral deliberations occur without asking whether or not people actually do, or even can, measure up to these standards.

I thus begin with the assumption that the human articulation of moral ideals is constrained by the basic architecture of the mind, the minds development, our core emotions, social psychology, and the limits on human capacity for rational deliberation. To demonstrate how this works in a world far messier and more complex than a laboratory setting, In answering these questions, the book addresses one of the most basic questions in moral theorywhat causes us to do goodbut it does so via a close examination of moral exemplars, not through religious or philosophical analysis.

Existing work on altruism and rescuers has moved beyond the level of correlational analyses to focus attention on an altruistic personality or identity.

As I explore what I believe will become one of the new frontiers in social scienceour ability to map the human mind and understand the importance of how people think about themselves and about others I pay special attention to the construals associated with the actors self-concept, her categorization of others, the extent to which certain values are integrated into her sense of self, the type and pattern of perspective taking, the actors sense of efficacy and extensivity, the development of moral salience, and the transformative aspect of altruistic acts for the agents identity.

This focus on cognitive construals has several advantages. It adds to our knowledge of the moral psychology and reveals something that is missing in the literature on moral choice. It increases our substantive understanding of the psychological foundations of altruism. It furthers knowledge of the critical self-concepts that lead to humane, moral responses to ethnic differences. And, finally, it advances work on the psychological foundations of moral and political activity.

Basic Argument and Organizational Format. Because of the interest in and the importance of the topic, I have tried to craft a work that is scholarly yet accessible to the intelligent lay reader. To do this, material that buttresses my argument, but which is of a more academic interest, is placed in appendices and notes. The basic text of the book itself has been pared down to provide focus to my essential argument.

What is the basic argument in this volume? Essentially, the stories analyzed here suggest ethical acts emerge not from choice so much as through our sense of who we are, through our identities.

The book opens with a prologue that uses an exchange with one rescuer to address issues of memory and the ethics of interviewing. It then presents the rescuers stories. Because understanding rescuers moral psychology means interpreting intricate and subtle cognitive differences, I am careful to document these perspectives. I do so through extensive presentation of the raw data, the narrative transcriptions of minimally edited interviews conducted between 1988 and 1999. The heart of the book thus presents a cognitive view of moral choice through the use of autobiographical sketches, told in the speakers own words.

Although I interviewed many survivors and rescuers, all certified by Yad Vashem, this book concentrates on the stories of five rescuers. Margot was a wealthy German whose father was head of General Motors for Western Europe. Margot left the Third Reich in protest against Nazi policies, moving to Holland, where she worked to save Jews despite being arrested many times.

Otto was an ethnic German living in Czechoslovakia. Though offered opportunities both to profit from his German status and to sit out the war in India, Otto stayed in Prague, joined the Austrian Resistance movement, and saved over one hundred Jews before ending up in a concentration camp himself.

John was a Dutchman placed on the Gestapos Most Wanted List because he organized an escape network to take Jews to safety in Switzerland and Spain. Arrested five times, John was tortured but never revealed any information. He always managed to escape, even when most of his network was betrayed, and took important information to Eisenhower and the Allies in London.

Irene was a Polish nursing student when the war began. After the partition of Poland, Irene was pressed into slave labor. Yet she hid eighteen Jews in the home of a German major, for whom she was keeping house, and helped other Jews hidden in the woods.