Table of Contents

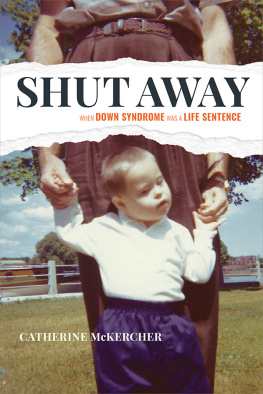

Once in a while a book comes along that breaks your heart wide open Shut Away is one of them, a gut-wrenching chronicle of a not-so-distant history, when society warehoused its most vulnerable members. With grace and clarity, journalist Catherine McKercher turns in a courageous memoir as she investigates what happened to her baby brother Bill, who was born with Downs Syndrome in the 1950s. Sent to a hospital school from the age of two, Bill becomes the powerful lens through which McKercher explores her familys experience and the government policies that gave rise to the massive institutions where children and adults with developmental disabilities were robbed of their rights, their potential, and love. Unsentimental and unflinching, Shut Away will make you weep for all the Bills and the crucial lessons humanity cannot afford to ignore from his story.

Carolyn Abraham, author of The Juggler's Children: A Journey into Family, Legend and the Genes that Bind Us

McKerchers meticulous research and precise, understated prose creates an unforgettable history of children placed in overcrowded, understaffed, and sometimes violent living conditions. Shut Away is a searingly honest portrait of a family ruptured by the decision to send away a very young boy and a moving portrait of a brother.

Judy McFarlane, author of Writing with Grace: A Journey Beyond Down Syndrome

McKerchers compelling and moving memoir illuminates the harsh realities of life in a long-stay residential facility, as well as the familial impact of the fateful decision to send her brother away.

David Wright, author of Downs: The History of a Disability

Copyright 2019 by Catherine McKercher.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Jill Ainsley.

Cover and page design by Julie Scriver.

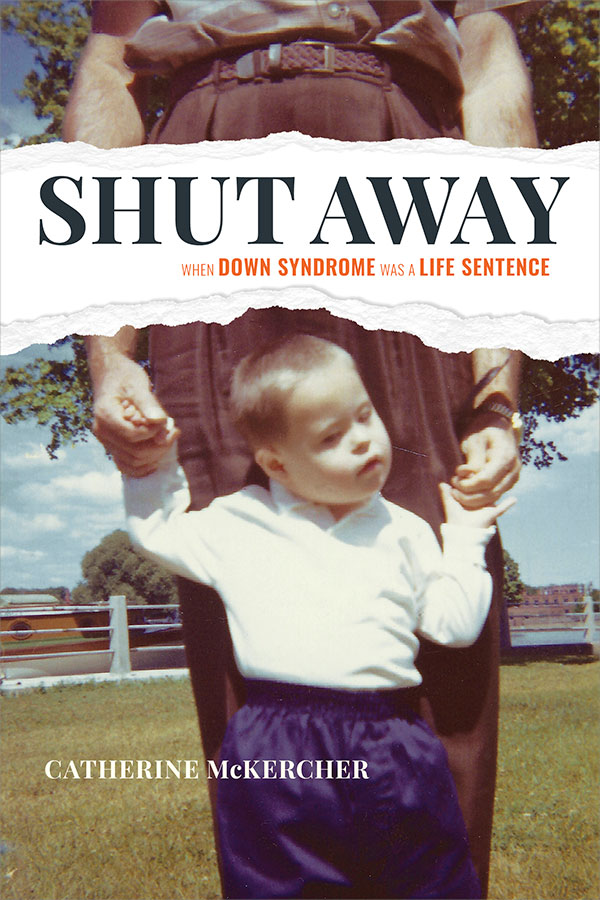

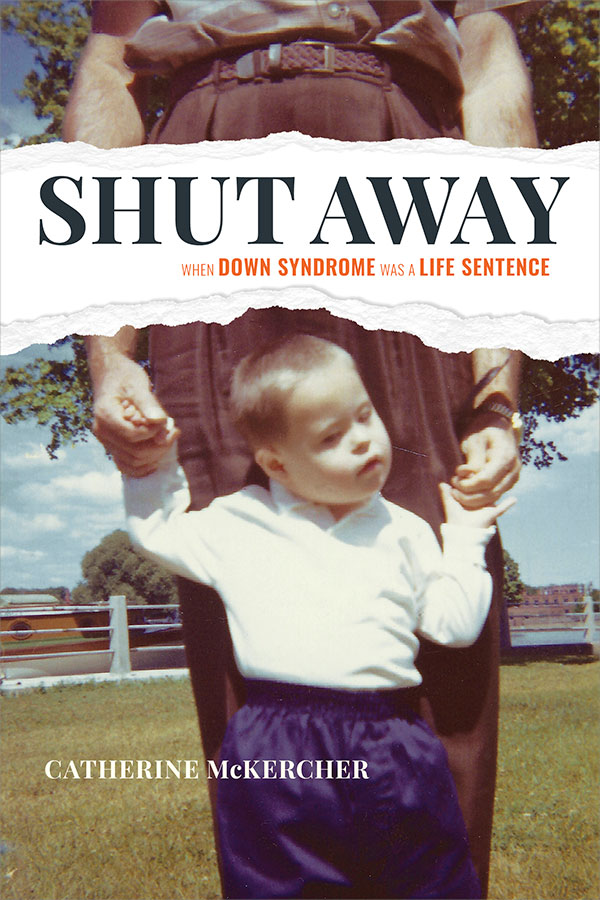

Cover image: Bill in the park at Smiths Falls, courtesy Catherine McKercher.

All photographs courtesy Catherine McKercher unless otherwise indicated.

Printed in Canada.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Shut away : when Down syndrome was a life sentence / Catherine McKercher.

Names: McKercher, Catherine, 1952- author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190090669 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190090782 | ISBN 9781773100982 (softcover) | ISBN 9781773101002 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781773100999 (Kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: McKercher, Catherine, 1952-Family. | LCSH: Down syndromePatients Family relationships. | LCSH: Intellectual disability facilities patientsAbuse ofCanada. | LCSH: People with mental disabilitiesAbuse ofCanada. | LCSH: People with mental disabilitiesCareCanada. | LCSH: Intellectual disability facilitiesCanada. | LCSH: Mental health facilitiesCanada.

Classification: LCC HV3008.C2 M35 2019 | DDC 362.20971dc23

Goose Lane Editions acknowledges the generous financial support of the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of New Brunswick.

Goose Lane Editions

500 Beaverbrook Court, Suite 330

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

www.gooselane.com

For Bill

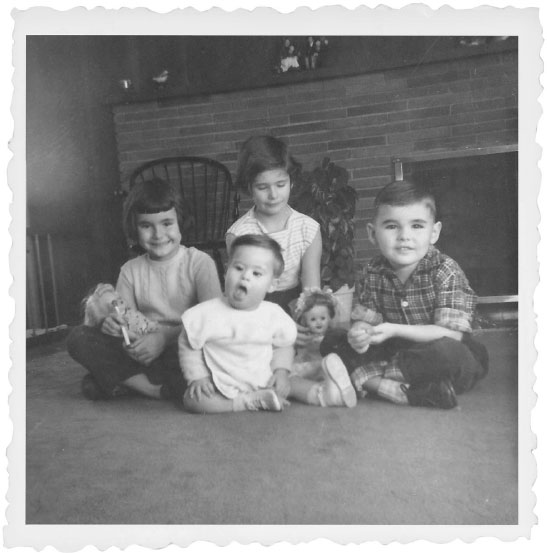

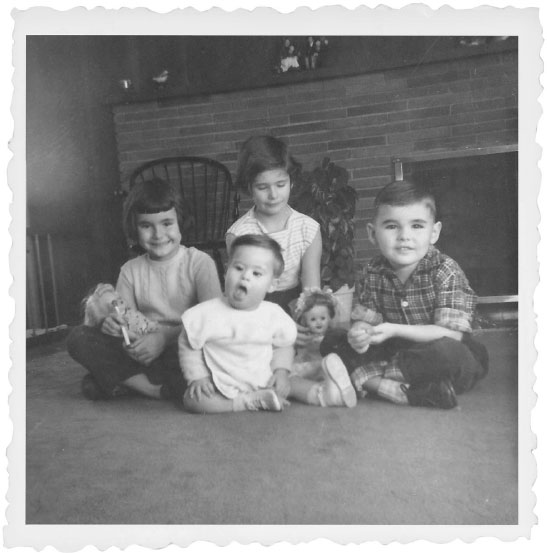

A rare snapshot of all four McKercher children at home in Ottawa. This was probably the last photo of Bill taken before his move to the Ontario Hospital School in February of 1959.

Contents

How many brothers and sisters do you have?

It was one of the first questions kids asked each other back in the 1950s and 1960s, when big families were common. I never knew how to answer it. Sometimes I told the truth and said our family had four kids, but the usual follow-up question What grades are they in? always tripped me up. My youngest brother wasnt in school, or at least not in a school like the ones we went to. He lived in something called a hospital school, an hours drive away. It didnt actually have grades, and he wasnt actually sick; he was there because he was born with something wrong with his brain. Having to explain all this to a kid Id just met was difficult, so I often said, I have an older sister and a younger brother. I knew lying was wrong but the lie was easier than the awkward truth. And if the stranger became a friend, I could correct the lie later.

As the years passed, it felt less and less like a lie.

My brother Bill was born with Down syndrome. My parents took him to the Ontario Hospital School at Smiths Falls when he was two and a half, and left him there for the rest of his life. We visited him faithfully as a family every month when we were children. After we grew up, Mom continued the visits, mostly on her own or with Dad. But in our house Bill was an absence, not a presence. He had no clothes in the closet, no toys in the toy chest, no books on the bookshelves. Framed portrait photos of the rest of us as babies hung on the wall of our parents bedroom. There were none of him just a snapshot, in profile, framed on Moms bureau. Our art projects and sports gear and noisy friends filled the house. We saw nothing of his. Yes, he was my brother, but his day-to-day life was utterly separate from mine.

The rupture in my family always troubled me, especially after I had children of my own. As a parent, the idea of sending my toddler to an institution was horrifying. Unimaginable, in fact. Yet my parents, who were kind and loving people, somehow found it justifiable, even reasonable, to exile their youngest child because he had Down syndrome. And they were not alone; thousands of other parents of children with intellectual disabilities had made the same decision. The phrase my parents used to explain it Sending Bill to Smiths Falls was the best thing we could have done for him became a family mantra of sorts, intoned whenever talk turned to Bill. I heard it countless times growing up, and I sometimes said it myself. No one wanted to believe my parents well-intentioned decision might have been the wrong one, or that there were other, better, ways for Bill to live. When my own children began to echo it back to me, however, it stopped me cold. By the time they met their uncle Bill, around 1990, the idea of shutting a child away simply because he had Down syndrome sounded like something from the Dark Ages. It was the stuff of nightmares.

I made my living with words, first as a journalist and later as a journalism professor and scholar, and I thought often about writing about Bill over the years. But I rarely talked about it, in large part because I didnt know what I would say. When I retired four or five years ago, many friends and colleagues asked me what I going to do with my time. My stock answer was that, after working for forty years, my plan was to be, not to do. That was good for a laugh, and it deflected the question nicely. Over coffee one day with a colleague from another university, though, I surprised myself by blurting out a different answer. I told him I was thinking about writing a book about my youngest brother, who grew up in an institution for people with intellectual disabilities and died of a disease hed caught there. Bills short life cast a long shadow over my family, before and after my parents sent him away, and I wondered whether it might be time, at long last, to shine some light into that shadow. My colleague responded to the idea enthusiastically.